Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wage Determination and Imperfect Competition

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Booth, Alison L. Working Paper Wage Determination and Imperfect Competition IZA Discussion Papers, No. 8034 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Booth, Alison L. (2014) : Wage Determination and Imperfect Competition, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 8034, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/96758 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IZA DP No. 8034 Wage Determination and Imperfect Competition Alison Booth March 2014 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Wage Determination and Imperfect Competition Alison Booth Australian National University and IZA Discussion Paper No. -

Labour Supply

7/30/2009 Chapter 2 Labour Supply McGraw-Hill/Irwin Labor Economics, 4th edition Copyright © 2008 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 2- 2 Introduction to Labour Supply • This chapter: The static theory of labour supply (LS), i. e. how workers allocate their time at a point in time, plus some extensions beyond the static model (labour supply over the life cycle; household fertility decisions). • The ‘neoclassical model of labour-leisure choice’. - Basic idea: Individuals seek to maximise well -being by consuming both goods and leisure. Most people have to work to earn money to buy goods. Therefore, there is a trade-off between hours worked and leisure. 1 7/30/2009 2- 3 2.1 Measuring the Labour Force • The US de finit io ns in t his sect io n a re s imila r to t hose in N Z. - However, you have to know the NZ definitions (see, for example, chapter 14 of the New Zealand Official Yearbook 2008, and the explanatory notes in Labour Market Statistics 2008, which were both handed out in class). • Labour Force (LF) = Employed (E) + Unemployed (U). - Any person in the working -age population who is neither employed nor unemployed is “not in the labour force”. - Who counts as ‘employed’? Size of LF does not tell us about “intensity” of work (hours worked) because someone working ONE hour per week counts as employed. - Full-time workers are those working 30 hours or more per week. 2- 4 Measuring the Labour Force • Labor Force Participation Rate: LFPR = LF/P - Fraction of the working-age population P that is in the labour force. -

Neoliberal Austerity and Unemployment

E L C I ‘…following Stuckler and Basu (2013) T it is not economic downturns per se that R matter but the austerity and welfare A “reform” that may follow: that “austerity Neoliberal austerity kills” and – as I argue here – that it particularly “kills” those in lower socio- economic positions.’ and unemployment The scale of contemporary unemployment consequent upon David Fryer and Rose Stambe examine critical psychological issues neoliberal austerity programmes is colossal. According to labour market statistics released in June 2013 by the UK Neoliberal fiscal austerity policies I am really sorry to bother you again. Office for National Statistics, 2.51 million decrease public expenditure God. But I am bursting to tell you all people were unemployed in the UK through cuts to central and local the stuff that has been going on (tinyurl.com/neu9l47). This represents five government budgets, welfare behind your back since I first wrote to unemployed people competing for every services and benefits and you back in 1988. Oh God do you still vacancy. privatisation of public resources remember? Remember me telling Official statistics like these, which have resulting in job losses. This article you of the war that was going on persisted now for years, do not, of course, interrogates the empirical, against the poor and unemployed in prevent the British Prime Minister – theoretical, methodological and our working class communities? Do evangelist of neoliberal government - ideological relationships between you remember me telling you, God, asking in a speech delivered in June 2012 neoliberalism, unemployment and how the people in my community ‘Why has it become acceptable for many the discipline of psychology, were being killed and terrorised but people to choose a life on benefits?’ arguing that neoliberalism that there were no soldiers to be Talking of what he termed ‘Working Age constitutes rather than causes seen, no tanks, no bombs being Welfare’, Mr Cameron opined: ‘we have unemployment. -

Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism

DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM RESEARCH AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS DIVISION DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR MIKE MC CARTNEY DIRECTOR DR. EUGENE TIAN CHIEF STATE ECONOMIST FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 19, 2021 HAWAI‘I'S UNEMPLOYMENT RATE AT 7.3 PERCENT IN JULY Jobs increased by 53,000 over-the-year HONOLULU — The Hawai‘i State Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism (DBEDT) today announced that the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for July was 7.3 percent compared to 7.7 percent in June. Statewide, 598,850 were employed and 47,200 unemployed in July for a total seasonally adjusted labor force of 646,000. Nationally, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.4 percent in July, down from 5.9 percent in June. Seasonally Adjusted Unemployment Rate State of Hawai`i Jul 2019 - Jul 2021 28.0% 24.0% 20.0% 16.0% 12.0% 8.0% 4.0% 0.0% Ma Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Ma Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Jun Jul y 19 19 19 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 y20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 Percent 2.5 2.4 2.3 2.2 2.1 2.1 2.0 2.1 2.1 21. 21. 14. 14. 14. 14. 14. 10. 10. 10. 9.2 9.1 8.5 8.0 7.7 7.3 The unemployment rate figures for the State of Hawai‘i and the U.S. in this release are seasonally adjusted, in accordance with the U.S. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB). -

Chapter 16 Oligopoly and Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly

Chapter 16 “Game theory is the study of how people Oligopoly behave in strategic situations. By ‘strategic’ we mean a situation in which each person, when deciding what actions to take, must and consider how others might respond to that action.” Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly • “Oligopoly is a market structure in which only a few • “Figuring out the environment” when there are sellers offer similar or identical products.” rival firms in your market, means guessing (or • As we saw last time, oligopoly differs from the two ‘ideal’ inferring) what the rivals are doing and then cases, perfect competition and monopoly. choosing a “best response” • In the ‘ideal’ cases, the firm just has to figure out the environment (prices for the perfectly competitive firm, • This means that firms in oligopoly markets are demand curve for the monopolist) and select output to playing a ‘game’ against each other. maximize profits • To understand how they might act, we need to • An oligopolist, on the other hand, also has to figure out the understand how players play games. environment before computing the best output. • This is the role of Game Theory. Some Concepts We Will Use Strategies • Strategies • Strategies are the choices that a player is allowed • Payoffs to make. • Sequential Games •Examples: • Simultaneous Games – In game trees (sequential games), the players choose paths or branches from roots or nodes. • Best Responses – In matrix games players choose rows or columns • Equilibrium – In market games, players choose prices, or quantities, • Dominated strategies or R and D levels. • Dominant Strategies. – In Blackjack, players choose whether to stay or draw. -

Modern Monetary Theory: a Marxist Critique

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 2019 Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Michael Roberts [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Michael (2019) "Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.7.1.008316 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol7/iss1/1 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Monetary Theory: A Marxist Critique Abstract Compiled from a series of blog posts which can be found at "The Next Recession." Modern monetary theory (MMT) has become flavor of the time among many leftist economic views in recent years. MMT has some traction in the left as it appears to offer theoretical support for policies of fiscal spending funded yb central bank money and running up budget deficits and public debt without earf of crises – and thus backing policies of government spending on infrastructure projects, job creation and industry in direct contrast to neoliberal mainstream policies of austerity and minimal government intervention. Here I will offer my view on the worth of MMT and its policy implications for the labor movement. First, I’ll try and give broad outline to bring out the similarities and difference with Marx’s monetary theory. -

July Unemployment Rate Decreases to 5.8 Percent

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: September 16, 2021 Margaux Fontaine 401-209-0153 [email protected] Rhode Island-Based Jobs Rose by 800 from July; August Unemployment Rate Increases to 5.8 Percent CRANSTON, R.I. - The state’s seasonally adjusted Aug 21 Jul 21 Aug 20 unemployment rate was 5.8 percent in August, the Department of R.I. Unemployment Rate 5.8% 5.7% 12.6% Labor and Training announced Thursday. The August rate was up one-tenth of a percentage point from the revised July rate of 5.7 U.S. Unemployment Rate 5.2% 5.4% 8.4% percent. Last year the rate was 12.6 percent in August. R.I. Job Count (in thousands) 477.9 477.1 457.3 Highlights: The U.S. unemployment rate was 5.2 percent in August, down two-tenths of a percentage point from July. The U.S. rate was 8.4 The Rhode Island unemployment rate was 5.8 percent percent in August 2020. in August, up one-tenth of a percentage point from last month’s revised rate of 5.7 percent. The number of unemployed Rhode Island residents — those Through August, the Rhode Island economy has residents classified as available for and actively seeking recovered 78,700 or nearly 73 percent of the 108,000 jobs lost during the pandemic shutdown. employment — was 30,900, up 100 from July. The number of unemployed residents decreased by 35,800 over the year. The number of employed Rhode Island residents was 503,800, down 1,500 from July. -

A Supergame-Theoretic Model of Business Cycles and Price Wars During Booms

working paper department of economics A SUPERGAME-THEORETIC MODEL OF BUSINESS CYCLES AND PRICE WARS DURING BOOMS Julio J. Rotemberg and Garth Saloner* M.I.T. Working Paper #349 July 1984 massachusetts institute of technology 50 memorial drive Cambridge, mass. 021 39 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from IVIIT Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/supergametheoret349rote model of 'a supergame-theoretic BUSINESS CYCLES AOT) PRICE WARS DURING BOOMS Julio J. Rotemberg and Garth Saloner* ' M.I.T. Working Paper #349 July 1984 ^^ ""' and Department of Economics --P^^^i^J^' *Slo.n ;-..>>ool of Management Lawrence summers -^.any^helpful^^ .ei;ix;teful to ^ames.Poterba and ^^^^^^^ from the Mationax do conversations, Financial support is gratefully acknowledged.^ SEt8209266 and SES-8308782 respectively) 12 ABSTRACT This paper studies implicitly colluding oligopolists facing fluctuating demand. The credible threat of future punishments provides the discipline that facilitates collusion. However, we find that the temptation to unilaterally deviate from the collusive outcome is often greater when demand is high. To moderate this temptation, the optimizing oligopoly reduces its profitability at such times, resulting in lower prices. If the oligopolists' output is an input to other sectors, their output may increase too. This explains the co-movements of outputs which characterize business cycles. The behavior of the railroads in the 1880' s, the automobile industry in the 1950's and the cyclical behavior of cement prices and price-cost margins support our theory. (j.E.L. Classification numbers: 020, 130, 610). I. INTRODUCTION This paper has two objectives. First it is an exploration of the way in which oligopolies behave over the business cycle. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

Competitiveness and the Labour Market

Ministry of Finance WORKING PAPER No. 4 www.pm.gov.hu/ ÁGOTA SCHARLE COMPETITIVENESS AND THE LABOUR MARKET This paper was produced as part of the research project entitled ‘Economic competitiveness: recent trends and options for state intervention’ October 2003 This paper reflects the views of the author and does not represent the policies of the Ministry of Finance Author: Ágota Scharle Ministry of Finance [email protected] Series Editors: Orsolya Lelkes and Ágota Scharle Ministry of Finance Strategic Analysis Division The Strategic Analysis Division aims to support evidence-based policy-making in priority areas of financial policy. Its three main roles are to undertake long-term research projects, to make existing empirical evidence available to policy makers and to promote the application of advanced research methods in policy making. The Working Papers series serves to disseminate the results of research carried out or commissioned by the Ministry of Finance. Working Papers in the series can be downloaded from the web site of the Ministry of Finance: http://www.pm.gov.hu Series editors may be contacted at [email protected] 2 Summary If competitiveness is defined as growth potential, the competitiveness of the contribution of human resources to economic competitiveness labour market is determined by the size and skills of the labour force and the flexibility of the labour market. This paper aims to review available statistics and research and identify the major constraints on competitiveness and provide a starting point for subsequent research (see recommendations at the end). In Hungary, 60% of the working age population are in low activity rate employment or looking for work. -

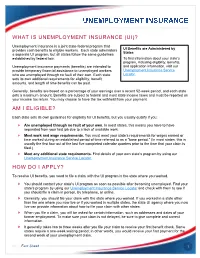

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements.