The Keynesian Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 9 Keynesian Models of Aggregate Demand

Economics 314 Coursebook, 2010 Jeffrey Parker 9 KEYNESIAN MODELS OF AGGREGATE DEMAND Chapter 9 Contents A. Topics and Tools ............................................................................ 2 B. Comparative-Static Analysis of the Closed-Economy Basic Keynesian Model 3 Expenditure equilibrium and the IS curve ....................................................................... 4 Expenditures and the IS curve ....................................................................................... 5 Money demand and monetary policy.............................................................................. 7 The LM curve .............................................................................................................. 8 The MP curve .............................................................................................................. 9 Aggregate demand and aggregate supply ......................................................................... 9 C. Some Simple Aggregate-Supply Models ............................................... 10 Case 1: Nominal-wage stickiness .................................................................................. 11 Case 2: Inflation stickiness with competitive labor market ............................................... 12 Case 3: Inflation stickiness with labor-market imperfections ............................................ 13 Case 4: Sticky wages with imperfect competition ............................................................ 13 D. The Open Economy ....................................................................... -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

Inventory Investment, Internal-Finance Fluctuations, and the Business Cycle

ROBERT E. CARPENTER Emory University STEVEN M. FAZZARI Washington University in St. Louis BRUCE C. PETERSEN Washington University in St. Lou is Inventory Investment, Internal-Finance Fluctuations, and the Business Cycle IT IS A well-known fact that inventory disinvestment can account for much of the movement in output during recessions. Almost one-half of the shortfall in output, averaged over the five interwar business cycles, can be accounted for by inventory disinvestment, and the proportion has been even larger for postwar recessions.' A lesser-known fact is that corporate profits, and therefore internal-finance flows, are also ex- tremely procyclical and tend to lead the cycle. Wesley Mitchell finds that the percentage change in corporate income over the business cycle is several times greater than that in any other macroeconomic series in his study.2 Robert Lucas lists the high conformity and large variation of corporate income as one of the seven main qualitative features of the business cycle.3 The volatility of internal finance, which is also com- We thank Lee Benham, Robert Chirinko, Mark Gertler, Simon Gilchrist, Edward Greenberg, Charles Himmelberg, Anil Kashyap, Louis Maccini, Dorothy Petersen, and Toni Whited for helpful comments, and Andrew Meyer, Bruce Rayton, and James Mom- tazee for excellent research assistance. Robert Parks and Daniel Levy provided technical assistance. We acknowledge financial support from the Jerome Levy Economics Institute, the University Research Committee of Emory University, and Washington University. 1. See Abramovitz (1950, p. 5) and Blinder and Maccini (199la). 2. Mitchell (1951, p. 286). These series include the rate of bankruptcy, employment, and pig iron production, among others. -

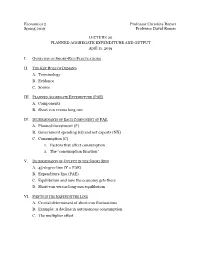

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

1 Keynesian Theory (IS-LM Model): How GDP and Interest Rates Are

Keynesian Theory (IS-LM Model): how GDP and interest rates are determined in Short Run with Sticky Prices. Historical background: The Keynesian Theory was proposed to show what could be done to shorten the Great Depression. key idea 1 is that during recessions producers have excessive capacity, they can supply any quantity at given price. That means the supply curve is flat (sticky price). In that case, the equilibrium quantity is determined by demand only. In other words, inadequate demand leads to insufficient quantity (recession). Recession can be avoided by increasing demand! Chapter 3: The Goods Market (Keynesian Cross) The key idea 2 is that, person A’s expenditure will become person B’s income, so B will spend, then person C’s income will rise, and C will spend, so on. In short, there are successive increases in output after someone spends. First of all, the aggregate demand for domestic goods can be decomposed as 푍 ≡ 퐶 + 퐼 + 퐺 + 푋 − 퐼푀 (푐표푛푠푢푚푝푡표푛 + 푛푣푒푠푡푚푒푛푡 + 푔표푣푒푟푛푚푒푛푡 푝푢푟푐ℎ푎푠푒 + 푒푥푝표푟푡 − 푚푝표푟푡) (1) This is an identity so we use ≡. In other words, such decomposition is always possible, see Table 3-1. Q1: which component will change if US government starts a new war against ISIS? Which component will be affected, in what way, by the fact that US dollar is appreciating? Next, we try to explain each component. For consumption, we let it be determined by disposable income. The consumption function is given by 퐶 = 퐶0 + 퐶1푌퐷 = 퐶0 + 퐶1(푌 − 푡푎푥 + 푡푟푎푛푠푓푒푟) (2) where 퐶0 is called _________________________________, and can be interpreted as___________________ 퐶1 is called _________________________________, and can be interpreted as___________________. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

The Macroeconomic Implications of Consumption: State-Of-Art and Prospects for the Heterodox Future Research

The macroeconomic implications of consumption: state-of-art and prospects for the heterodox future research Lídia Brochier1 and Antonio Carlos Macedo e Silva2 Abstract The recent US economic scenario has motivated a series of heterodox papers concerned with household indebtedness and consumption. Though discussing autonomous consumption, most of the theoretical papers rely on private investment-led growth models. An alternative approach is the so-called Sraffian supermultipler model, which treats long-run investment as induced, allowing for the possibility that other final demand components – including consumption – may lead long-run growth. We suggest that the dialogue between these approaches is not only possible but may prove to be quite fruitful. Keywords: Consumption, household debt, growth theories, autonomous expenditure. JEL classification: B59, E12, E21. 1 PhD Student, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 2 Professor at University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 1 1 Introduction Following Keynes’ famous dictum on investment as the “causa causans” of output and employment levels, macroeconomic literature has tended to depict personal consumption as a well-behaved and rather uninteresting aggregate demand component.3 To be sure, consumption is much less volatile than investment. Does it really mean it is less important? For many Keynesian economists, the answer is – or at least was, until recently – probably positive. At any rate, the American experience has at least demonstrated that consumption is important, and not only because it usually represents more than 60% of GDP. After all, in the U.S., the very ratio between consumption and GDP has been increasing since the 1980s, in spite of the stagnant real labor income and the growing income inequality. -

Mr. Keynes and the "Classics" Again: an Alternative Interpretation

Mr. Keynes and the "Classics" Again: An Alternative Interpretation David Colander Middlebury College It will be admitted by the least charitable reader that the textbook exposition of Keynesian economics and its integration with Classical economics are elegant. But it is also clear to most people who have read Keynes that the AS/AD textbook exposition of Keynesian economics embodies ideas that are not to be found in The General Theory, and includes others that Keynes went to great lengths to repudiate. In this paper I offer an alternative AS/AD exposition of Keynesian economics which better captures the essence of Keynes' ideas and offers a superior integration of Keynesian economics with Classical economics. The underlying ideas expressed in my alternative exposition are not original. They can be found, in varying degrees, in the work of Keynes, Don Patinkin, Abba Lerner, James Tobin, Paul Davidson, Robert Clower, Axel Leijonhufvud, and some of the New Keynesians, to mention only a few of those who have provided richer alternative interpretations of Keynesian economics. But these alternative interpretations are known primarily by macroeconomic and history of thought specialists. They have not become part of the standard core of macroeconomic theory as presented in the introductory and intermediate texts. Indeed, as I can testify to by experience, any attempt to include a discussion of these alternative interpretations in introductory or intermediate texts is met with great hostility by reviewers as being outside of the standard core. Despite the multitude of interpretations of Keynesian macroeconomics, only three have become part of the core of macroeconomics: Samuelson's Keynesian Cross, Hicks' IS/LM model, and a generic aggregate supply-demand model. -

Page 1 Econ 303: Intermediate Macroeconomics I Dr. Sauer

Econ 303: Intermediate Macroeconomics I Dr. Sauer Sample Questions for Exam #1 1. Variables that a model tries to explain are called: A) endogenous. B) exogenous. C) market clearing. D) fixed. 2. A measure of how fast prices are rising is called the: A) growth rate of real GDP. B) inflation rate. C) unemployment rate. D) market-clearing rate. 3. Deflation occurs when: A) real GDP decreases. B) the unemployment rate decreases. C) prices fall. D) prices increase, but at a slower rate. 4. A severe recession is called a(n): A) depression. B) deflation. C) exogenous event. D) market-clearing assumption. 5. The assumption of flexible prices is a more plausible assumption when applied to price changes that occur: A) from minute to minute. B) from year to year. C) in the long run. D) in the short run. 6. During the period between 1900 and 2000, the unemployment rate in the United States was highest in the: A) 1920s. B) 1930s. C) 1970s. D) 1980s. 7. The assumption of continuous market clearing means that: A) sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. B) buyers can buy all that they want at the going price. C) in any given month, buyers can buy all that they want and sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. D) at any given instant, buyers can buy all that they want and sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. 8. The total income of everyone in the economy adjusted for the level of prices is called: A) a recession. -

Chapter 4.Pmd

Chapter4 Determination of Income and Employment We have so far talked about the national income, price level, rate of interest etc. in an ad hoc manner – without investigating the forces that govern their values. The basic objective of macroeconomics is to develop theoretical tools, called models, capable of describing the processes which determine the values of these variables. Specifically, the models attempt to provide theoretical explanation to questions such as what causes periods of slow growth or recessions in the economy, or increment in the price level, or a rise in unemployment. It is difficult to account for all the variables at the same time. Thus, when we concentrate on the determination of a particular variable, we must hold the values of all other variables constant. This is a stylisation typical of almost any theoretical exercise and is called the assumption of ceteris paribus, which literally means ‘other things remaining equal’. You can think of the procedure as follows – in order to solve for the values of two variables x and y from two equations, we solve for one variable, say x, in terms of y from one equation first, and then substitute this value into the other equation to obtain the complete solution. We apply the same method in the analysis of the macroeconomic system. In this chapter we deal with the determination of National Income under the assumption of fixed price of final goods and constant rate of interest in the economy. The theoretical model used in this chapter is based on the theory given by John Maynard Keynes. -

Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman Some Answers 1) A. During the Depression, the Federal Reserve Enacted Policies That Reduce

Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman Some Answers 1) a. During the Depression, the Federal Reserve enacted policies that reduced the money supply. Sketch a graph and on it indicate what this would do to the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves in the short run if output were originally at its natural level. What would happen to output and the aggregate price level in the short run? b. On the same graph, indicate what would happen to the short-run aggregate supply and aggregate demand curves over time if there were no further reductions in the money supply. Consequently, what would happen to output and price level over time? c. What is the final effect of this policy on output and the price level in the long run? Reduction of the money supply shifts the Aggregate Demand schedule and brings the economy from 1 to 2 in the short run. If the Fed does nothing else, the economy would find its way to 3 by a slow movement along the AD’ curve (or equivalently, shifts in the SRAS curve). The FINAL effect is no long run change in output, but a permanently lower price level. P LRAS 2 1 SRAS AD 3 AD’ Y Page 1 of 6 Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman 2) Throughout much of the 1990s, the United States experienced declining energy prices. Assume that the U.S. economy was in long-run equilibrium before these declines began. a. Use the aggregate demand-aggregate supply model to illustrate graphically the short-run AND long-run impact of this decline on output and prices. -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics