The Way Brands Work: Consumers' Understanding of the Creation and Usage of Brands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Culture and Postmodernism

Consumer Culture and Postmodernism Prasidh Raj SINGH1 2 Abstract: Postmodernism is a variety of meanings and definitions, is used to refer to many aspects of social life from musical forms and styles, literature and fine art through to philosophy, history and especially the mass media and consumer culture. Post modernism is a slippery term that is used by writers to refer to several different things. Featherstone (1991) points out the term has been used to refer to new developments in intellectual and cultural theory. The suggestion that our subjective experience of everyday life and our sense of identity has somehow changed significantly in recent years. The view that capitalist or industrial societies have reached new and important stages in their development, the shift from modernity to post-modernity. Consumer culture is also play a vital role in the society, consumer culture may be defined as a day to day change in the taste of consumer behaviour. The term “consumer culture” refers to cultures in which mass consumption and production both fuel the economy and shape perceptions, values, desires, and constructions of personal identity. Economic developments, demographic trends, and new technologies profoundly influence the scope and scale of consumer culture. Social class, gender, ethnicity, region, and age all affect definitions of consumer identity and attitudes about the legitimacy of consumer centred lifestyle. Keywords: Postmodernism, Consumer culture, Modernity, Consumer identity, Ethnicity 1 Prasidh Raj SINGH – Student at National Law University, Orissa India, Email : [email protected] , Mobile no. +9583237911 2 Paper presented at the International Scientific Conference "Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty" organized by the Lumen Research Center in Humanistic Sciences in partnership with the Romanian Academy, Iasi Branch - "AD Xenopol" Institute, "Al. -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

Research Archive

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Research Archive Citation for published version: Catulli, M., Cook, M. and Potter, S., ‘Product Service Systems Users and Harley Davidson Riders: The Importance of Consumer Identity in the Diffusion of Sustainable Consumption Solutions’, Journal of Industrial Ecology, December 2016. Published by Wiley. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12518 Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Users should always cite the published version of record. Copyright and Reuse: © 2016 by Yale University. This article may be used for non- commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] PSS Users and Harley Davidson Riders: the importance of consumer identity in the diffusion of sustainable consumption solutions Summary This paper sets out an approach to researching socio-cultural aspects of Product Service Systems (PSS) consumption in consumer markets. PSS are relevant to Industrial Ecology as they may form part of the mix of innovations that move society toward more sustainable material and energy flows. The paper uses two contrasting case studies drawing on ethnographic analysis, Harley Davidson motorcycles and Zip Car Car Club, one a case of consumption involving ownership, the other without. The analysis draws on Consumer Culture Theory to explicate the socio- cultural, experiential, symbolic and ideological aspects of these case studies, focusing on product ownership. -

Durham Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Durham Research Online Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 22 August 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Obiegbu, J and Larsen, G and Ellis, N (2019) 'Experiential brand loyalty : towards an extended conceptualization of consumer allegiance to brands.', Marketing theory. Further information on publisher's website: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mtq Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk Experiential Brand Loyalty: Towards an Extended Conceptualisation of Consumer Allegiance to Brands James Obiegbu, Durham University Gretchen Larsen, Durham University Nick Ellis, Durham University 19 July 2019 Forthcoming in Marketing Theory Abstract This paper synthesises experiential and meaning-based dimensions of loyalty in order to extend the brand loyalty canon. -

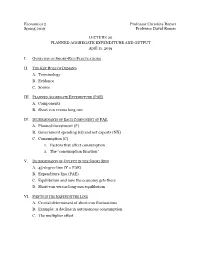

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

The Macroeconomic Implications of Consumption: State-Of-Art and Prospects for the Heterodox Future Research

The macroeconomic implications of consumption: state-of-art and prospects for the heterodox future research Lídia Brochier1 and Antonio Carlos Macedo e Silva2 Abstract The recent US economic scenario has motivated a series of heterodox papers concerned with household indebtedness and consumption. Though discussing autonomous consumption, most of the theoretical papers rely on private investment-led growth models. An alternative approach is the so-called Sraffian supermultipler model, which treats long-run investment as induced, allowing for the possibility that other final demand components – including consumption – may lead long-run growth. We suggest that the dialogue between these approaches is not only possible but may prove to be quite fruitful. Keywords: Consumption, household debt, growth theories, autonomous expenditure. JEL classification: B59, E12, E21. 1 PhD Student, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 2 Professor at University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil. [email protected] 1 1 Introduction Following Keynes’ famous dictum on investment as the “causa causans” of output and employment levels, macroeconomic literature has tended to depict personal consumption as a well-behaved and rather uninteresting aggregate demand component.3 To be sure, consumption is much less volatile than investment. Does it really mean it is less important? For many Keynesian economists, the answer is – or at least was, until recently – probably positive. At any rate, the American experience has at least demonstrated that consumption is important, and not only because it usually represents more than 60% of GDP. After all, in the U.S., the very ratio between consumption and GDP has been increasing since the 1980s, in spite of the stagnant real labor income and the growing income inequality. -

Chapter 4.Pmd

Chapter4 Determination of Income and Employment We have so far talked about the national income, price level, rate of interest etc. in an ad hoc manner – without investigating the forces that govern their values. The basic objective of macroeconomics is to develop theoretical tools, called models, capable of describing the processes which determine the values of these variables. Specifically, the models attempt to provide theoretical explanation to questions such as what causes periods of slow growth or recessions in the economy, or increment in the price level, or a rise in unemployment. It is difficult to account for all the variables at the same time. Thus, when we concentrate on the determination of a particular variable, we must hold the values of all other variables constant. This is a stylisation typical of almost any theoretical exercise and is called the assumption of ceteris paribus, which literally means ‘other things remaining equal’. You can think of the procedure as follows – in order to solve for the values of two variables x and y from two equations, we solve for one variable, say x, in terms of y from one equation first, and then substitute this value into the other equation to obtain the complete solution. We apply the same method in the analysis of the macroeconomic system. In this chapter we deal with the determination of National Income under the assumption of fixed price of final goods and constant rate of interest in the economy. The theoretical model used in this chapter is based on the theory given by John Maynard Keynes. -

The Sraffian Supermultiplier and the Stylized Facts

Texto para Discussão 005 | 2019 Discussion Paper 005 | 2019 Stagnation and unnaturally low interest rates: a simple critique of the amended New Consensus and the Sraffian supermultiplier alternative Franklin Serrano Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Ricardo Summa Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Vivian Garrido Moreira Universidade Estadual do Centro Oeste - UNICENTRO This paper can be downloaded without charge from http://www.ie.ufrj.br/index.php/index-publicacoes/textos-para-discussao Stagnation and unnaturally low interest rates: a simple critique of the amended New Consensus and the Sraffian supermultiplier alternative1 March. 2019 Franklin Serrano Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Ricardo Summa Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Vivian Garrido Moreira Universidade Estadual do Centro Oeste – UNICENTRO Abstract This paper argues that the amended versions (financial wedge and secular stagnation) of the simple pragmatic New Consensus model are as open to theretical criticism as the original one. We show that: (1) the real natural rate of interest is unlikely to be negative and (2) it (inconsistently) depends on the neoclassical investment function drawn at a position of full employment, in a model which the economy is demand constrained; (3) both investment and full employment saving are induced by the trend of demand in the longer run and this challenges the usefulness of the notion of a natural or neutral rate of interest, which (4) are also subject to the sraffian capital critique. This is then constrasted to an alternative simple Sraffian Supermultiplier model in which the interest rate and the financial wedge are distributive instead of allocative variables, and there is no natural rate of interest since in the longer run there is no trade-off between consumption and investment and also no full employment of labor. -

Association for Consumer Research

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 Understanding Consumer Culture: the Role of “Food” As an Important Cultural Category Marcelo Fonseca, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (Unisinos); Brazil Food represents, in a symbolic manner, the dominant ways of a given society. Through an analysis of its habits and consumption practices, it is possible to understand a series of meanings associated with the production of identities, the establishment and maintenance of social relationships, and cultural changes in a society. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to identify, through the classification proposed by Arnould and Thompson (2005) regarding the different research programs on CCT, a group of studies which, in some way, has dealt with the food topic in different contexts associated with consumer culture. [to cite]: Marcelo Fonseca (2008) ,"Understanding Consumer Culture: the Role of “Food” As an Important Cultural Category", in LA - Latin American Advances in Consumer Research Volume 2, eds. Claudia R. Acevedo, Jose Mauro C. Hernandez, and Tina M. Lowrey, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 28-33. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/14134/la/v2_pdf/LA-02 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or use this work in whole or in part, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com/. Understanding Consumer Culture: The Role of “Food” as an Important Cultural Category Marcelo Jacques Fonseca, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos–UNISINOS, Brasil ABSTRACT At last, on the basis of the classification proposed by Arnould Food represents, in a symbolic manner, the dominant ways of and Thompson (2005) regarding different research programs on a given society. -

Joana David Avritzer Debt-Led Growth and Its Financial Fragility: An

Joana David Avritzer Debt-led growth and its financial fragility: an investigation into the dynamics of a supermultiplier model March 2021 Working Paper 06/2021 Department of Economics The New School for Social Research The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the New School for Social Research. © 2021 by Joana David Avritzer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit is given to the source. Debt-led growth and its financial fragility: an investigation into the dynamics of a supermultiplier model Joana David Avritzer1 This paper discusses the financial sustainability of demand-led growth models. We assume a supermultiplier growth model in which household consumption is the autonomous component of demand that drives growth and discuss the financial sustainability of such dynamics of growth from the perspective of the working households. We show that for positive rates of growth the model converges to an equilibrium where worker households are accumulating debt and not wealth. We also show that when the economy is growing at a rate that is positive, and between 2% and 4.4%, the dynamics of the model also implies that households will not be able to service their debt at the point of full long run equilibrium. We then conclude that this household debt-financed consumption pattern of economic growth generates an internal dynamic that leads to financial instability. Keywords: household debt dynamics, debt-financed consumption, growth and financial fragility; JEL Classification: E11, E12, E21, O41. 1 Connecticut College and IRID-UFRJ, email: [email protected]; 1. -

Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research Author(S): Eric J

Journal of Consumer Research Inc. Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research Author(s): Eric J. Arnould and Craig J. Thompson Source: The Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 31, No. 4 (March 2005), pp. 868-882 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/426626 . Accessed: 06/05/2011 14:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Journal of Consumer Research Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Consumer Research.