The Consumption Function: a New Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 17: Consumption 1

11/6/2013 Keynes’s conjectures Chapter 17: Consumption 1. 0 < MPC < 1 2. Average propensity to consume (APC) falls as income rises. (APC = C/Y ) 3. Income is the main determinant of consumption. CHAPTER 17 Consumption 0 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 1 The Keynesian consumption function The Keynesian consumption function As income rises, consumers save a bigger C C fraction of their income, so APC falls. CCcY CCcY c c = MPC = slope of the 1 CC consumption APC c C function YY slope = APC Y Y CHAPTER 17 Consumption 2 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 3 Early empirical successes: Problems for the Results from early studies Keynesian consumption function . Households with higher incomes: . Based on the Keynesian consumption function, . consume more, MPC > 0 economists predicted that C would grow more . save more, MPC < 1 slowly than Y over time. save a larger fraction of their income, . This prediction did not come true: APC as Y . As incomes grew, APC did not fall, . Very strong correlation between income and and C grew at the same rate as income. consumption: . Simon Kuznets showed that C/Y was income seemed to be the main very stable in long time series data. determinant of consumption CHAPTER 17 Consumption 4 CHAPTER 17 Consumption 5 1 11/6/2013 The Consumption Puzzle Irving Fisher and Intertemporal Choice . The basis for much subsequent work on Consumption function consumption. C from long time series data (constant APC ) . Assumes consumer is forward-looking and chooses consumption for the present and future to maximize lifetime satisfaction. Consumption function . Consumer’s choices are subject to an from cross-sectional intertemporal budget constraint, household data a measure of the total resources available for (falling APC ) present and future consumption. -

BIS Working Papers No 136 the Price Level, Relative Prices and Economic Stability: Aspects of the Interwar Debate by David Laidler* Monetary and Economic Department

BIS Working Papers No 136 The price level, relative prices and economic stability: aspects of the interwar debate by David Laidler* Monetary and Economic Department September 2003 * University of Western Ontario Abstract Recent financial instability has called into question the sufficiency of low inflation as a goal for monetary policy. This paper discusses interwar literature bearing on this question. It begins with theories of the cycle based on the quantity theory, and their policy prescription of price stability supported by lender of last resort activities in the event of crises, arguing that their neglect of fluctuations in investment was a weakness. Other approaches are then taken up, particularly Austrian theory, which stressed the banking system’s capacity to generate relative price distortions and forced saving. This theory was discredited by its association with nihilistic policy prescriptions during the Great Depression. Nevertheless, its core insights were worthwhile, and also played an important part in Robertson’s more eclectic account of the cycle. The latter, however, yielded activist policy prescriptions of a sort that were discredited in the postwar period. Whether these now need re-examination, or whether a low-inflation regime, in which the authorities stand ready to resort to vigorous monetary expansion in the aftermath of asset market problems, is adequate to maintain economic stability is still an open question. BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. -

Shopping Enjoyment and Obsessive-Compulsive Buying

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) DOI: 10.7176/EJBM Vol.11, No.3, 2019 Young Buyers: Shopping Enjoyment and Obsessive-Compulsive Buying Ayaz Samo 1 Hamid Shaikh 2 Maqsood Bhutto 3 Fiza Rani 3 Fayaz Samo 2* Tahseen Bhutto 2 1.School of Business Administration, Shah Abdul Latif University, Khairpur, Sindh, Pakistan 2.School of Business Administration, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian, China 3.Sukkur Institute of Business Administration, Sindh, Pakistan Abstract The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the relationship between hedonic shopping motivations and obsessive- compulsive shopping behavior from youngsters’ perspective. The study is based on the survey of 615 young Chinese buyers (mean age=24) and analyzed through Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The findings show that adventure seeking, gratification seeking, and idea shopping have a positive effect on obsessive-compulsive buying, whereas role shopping and value shopping have a negative effect on obsessive-compulsive buying. However, social shopping is found to be insignificant to obsessive-compulsive buying. The study has a number of implications. Marketers should display more information about latest trends and fashions, as young buyers are found to shop for ideas and information. Managers should design the layouts with more exciting and impressive features, as these buyers are found to shop for adventure and gratification. Salesmen should take greater care into consideration while offering them to buy products such as gifts, souvenir etc. for their dear ones, as these buyers are less likely to enjoy buying for others. Moreover, business managers should less rely on discount promotions, as this consumer segment is found to be less likely to shop for discounts and bargains. -

What Role Does Consumer Sentiment Play in the U.S. Economy?

The economy is mired in recession. Consumer spending is weak, investment in plant and equipment is lethargic, and firms are hesitant to hire unemployed workers, given bleak forecasts of demand for final products. Monetary policy has lowered short-term interest rates and long rates have followed suit, but consumers and businesses resist borrowing. The condi- tions seem ripe for a recovery, but still the economy has not taken off as expected. What is the missing ingredient? Consumer confidence. Once the mood of consumers shifts toward the optimistic, shoppers will buy, firms will hire, and the engine of growth will rev up again. All eyes are on the widely publicized measures of consumer confidence (or consumer sentiment), waiting for the telltale uptick that will propel us into the longed-for expansion. Just as we appear to be headed for a "double-dipper," the mood swing occurs: the indexes of consumer confi- dence register 20-point increases, and the nation surges into a prolonged period of healthy growth. oes the U.S. economy really behave as this fictional account describes? Can a shift in sentiment drive the economy out of D recession and back into good health? Does a lack of consumer confidence drag the economy into recession? What causes large swings in consumer confidence? This article will try to answer these questions and to determine consumer confidence’s role in the workings of the U.S. economy. ]effre9 C. Fuhrer I. What Is Consumer Sentitnent? Senior Econotnist, Federal Reserve Consumer sentiment, or consumer confidence, is both an economic Bank of Boston. -

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP)

AP Macroeconomics: Vocabulary 1. Aggregate Spending (GDP): The sum of all spending from four sectors of the economy. GDP = C+I+G+Xn 2. Aggregate Income (AI) :The sum of all income earned by suppliers of resources in the economy. AI=GDP 3. Nominal GDP: the value of current production at the current prices 4. Real GDP: the value of current production, but using prices from a fixed point in time 5. Base year: the year that serves as a reference point for constructing a price index and comparing real values over time. 6. Price index: a measure of the average level of prices in a market basket for a given year, when compared to the prices in a reference (or base) year. 7. Market Basket: a collection of goods and services used to represent what is consumed in the economy 8. GDP price deflator: the price index that measures the average price level of the goods and services that make up GDP. 9. Real rate of interest: the percentage increase in purchasing power that a borrower pays a lender. 10. Expected (anticipated) inflation: the inflation expected in a future time period. This expected inflation is added to the real interest rate to compensate for lost purchasing power. 11. Nominal rate of interest: the percentage increase in money that the borrower pays the lender and is equal to the real rate plus the expected inflation. 12. Business cycle: the periodic rise and fall (in four phases) of economic activity 13. Expansion: a period where real GDP is growing. 14. Peak: the top of a business cycle where an expansion has ended. -

Three Revolutions in Macroeconomics: Their Nature and Influence

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Laidler, David Working Paper Three revolutions in macroeconomics: Their nature and influence EPRI Working Paper, No. 2013-4 Provided in Cooperation with: Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI), Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario Suggested Citation: Laidler, David (2013) : Three revolutions in macroeconomics: Their nature and influence, EPRI Working Paper, No. 2013-4, The University of Western Ontario, Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI), London (Ontario) This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/123484 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Nber Working Paper Series David Laidler On

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DAVID LAIDLER ON MONETARISM Michael Bordo Anna J. Schwartz Working Paper 12593 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12593 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2006 This paper has been prepared for the Festschrift in Honor of David Laidler, University of Western Ontario, August 18-20, 2006. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2006 by Michael Bordo and Anna J. Schwartz. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. David Laidler on Monetarism Michael Bordo and Anna J. Schwartz NBER Working Paper No. 12593 October 2006 JEL No. E00,E50 ABSTRACT David Laidler has been a major player in the development of the monetarist tradition. As the monetarist approach lost influence on policy makers he kept defending the importance of many of its principles. In this paper we survey and assess the impact on monetary economics of Laidler's work on the demand for money and the quantity theory of money; the transmission mechanism on the link between money and nominal income; the Phillips Curve; the monetary approach to the balance of payments; and monetary policy. Michael Bordo Faculty of Economics Cambridge University Austin Robinson Building Siegwick Avenue Cambridge ENGLAND CD3, 9DD and NBER [email protected] Anna J. Schwartz NBER 365 Fifth Ave, 5th Floor New York, NY 10016-4309 and NBER [email protected] 1. -

Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: National Saving and Economic Performance Volume Author/Editor: B. Douglas Bernheim and John B. Shoven, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-04404-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bern91-2 Conference Date: January 6-7, 1989 Publication Date: January 1991 Chapter Title: Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence Chapter Author: Christopher D. Carroll, Lawrence H. Summers Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5995 Chapter pages in book: (p. 305 - 348) 10 Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence Christopher D. Carroll and Lawrence H. Summers 10.1 Introduction The idea that consumers allocate their consumption over time so as to max- imize a stable individualistic utility function provides the basis for almost all modem work on the determinants of consumption and saving decisions. The celebrated life-cycle and permanent income hypotheses represent not so much alternative theories of consumption as alternative empirical strategies for fleshing out the same basic idea. While tests of particular implementations of these theories sometimes lead to statistical rejections, life-cycle/permanent income theories succeed in unifying a wide range of diverse phenomena. It is probably fair to accept Franc0 Modigliani’s ( 1980) characterization that “the Life Cycle Hypothesis has proved a very fruitful hypothesis, capable of inte- grating a large variety of facts concerning individual and aggregate saving behaviour.” This paper argues, however, that both permanent income and, to an only slightly lesser extent, life-cycle theories as they have come to be implemented in recent years are inconsistent with the grossest features of cross-country and cross-section data on consumption and income and income growth. -

The Time Series Consumption Function Revisited

ALAN S. BLINDER Brookings Institution and Princeton University ANGUS DEATON Princeton University The Time Series Consumption Function Revisited THERELATIONSHIP between consumer spending and income is one of the oldest statistical regularitiesof macroeconomics-and one of the stur- diest. Like the aging movie star, it needs a little touching up now and again, but always seems to come bouncingback. A dozen yearsago, boththe theoreticalderivation and the econometric form of the aggregateconsumption function were considered settled. Most economists adheredto one of two ways of puttingFisher's theory of intertemporaloptimization into operation: Milton Friedman's per- manent income hypothesis (henceforth, PIH) or Franco Modigliani's life-cycle hypothesis (henceforth,LCH). ' Since each variantseemed to have sound theoretical underpinnings,and since the two had similar econometricforms that explainedthe data well and had similarimplica- tions for policy, there was not a greatdeal to quarrelabout. Perhapsthe most contentious empirical issue was the apparently large marginal This paperhas benefitedfrom the commentsand suggestionsof AlbertAndo, Whitney Newey, and members of the Brookings Panel and from seminar presentationsat the Universityof Warwick,Princeton University, and Johns Hopkins University.We thank Peter Rathjensand Lori Gruninfor researchassistance and the National Science Foun- dationfor financialsupport. 1. Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function (Princeton University Press, 1957); Franco Modigliani and Richard Brumberg, -

CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2020)

1 CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2020) NAME: David E.W. Laidler NATIONALITY: Canadian (also U.K.) DATE OF BIRTH: 12 August 1938 MARITAL STATUS: Married, one daughter HOME ADDRESS: 45 - 124 North Centre Road London, Ontario Canada N5X 4R3 Telephone: (519) 673-3014 FAX: (519) 661-3666 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES HELD: Tynemouth School, Tynemouth, Northumberland, England, GCE 'O' Level 1953, 'A' Level, 1955, 'S' Level, 1956 London School of Economics, B.Sc. Econ. (Economics Analytic and Descriptive) 1st Class Honours, 1959 University of Syracuse, M.A. (Economics), 1960 University of Chicago, Ph.D. (Economics), 1964 University of Manchester, M.A. 1973 (not an "earned" degree) University of Western Ontario, LL.D.(h.c.) 2016 SCHOLARSHIPS, FELLOWSHIPS AND ACADEMIC HONOURS: 1956-1959 State Scholarship 1959-1960 University of Syracuse: University Fellowship 1960-1961 University of Chicago: Edward Hillman Fellowship 1962-1963 University of Chicago: Earhart Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship 1972 British Association for the Advancement of Science, Lister Lecture, to be given by a distinguished contributor to the Social Sciences under 35 years of age 1982 - Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada 1987-1988 President, Canadian Economics Association/Association Canadienne d'Economique 1988-1989 Faculty of Social Science Research Professor, University of Western Ontario 1994 Douglas Purvis Memorial Prize, awarded by the Canadian Economics Association for a significant work on Canadian Economic Policy (joint recipient with W.B.P. Robson) 1999 Hellmuth Prize for distinguished research in the Humanities and Social Sciences by a member of the faculty of the University of Western Ontario 2004-2005 Donner Prize for the best book of the year on Canadian public policy. -

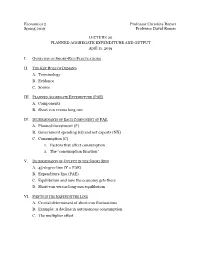

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

Case, Fair and Oster Macroeconomics Chapter 8 – Aggregate Expenditure and Equilibrium Output Problem 1. Terminology A. MPC

Case, Fair and Oster Macroeconomics Chapter 8 – Aggregate Expenditure and Equilibrium Output Problem 1. Terminology a. MPC and the multiplier. Multiplier = 1 / (1.0 – MPC) b. Actual and planned investment. Divergence between the two means the economy is out of equilibrium, since the Keynesian equilibrium condition is PAE = GDP or PAE = Y. (PAE = Planned aggregate expenditure) Divergence is due to unplanned inventory changes (an increase in inventory may be due to failure to make anticipated sales, and will result in lower orders to supplying firms and hence to lower employment and GDP. c.Aggregate expenditure and Real GDP. If real aggregate expenditure is equal to real GDP, the economy is in Keynesian equilibrium. Note that the following two chapters always use real GDP, and we won't worry about inflation for these chapters. d.Aggregate output and aggregate income. The circular flow means these are the same thing, looked at from two different perspectives (seller and consumer). Problem 2. Republic of Yuck. Real GDP = 200 billion (note that this may not be an equilibrium value) Planned investment = 75 billion Consumption function : C = 0.75 Y (since 25 percent of income is saved, 75 percent is consumed) Simplest of all Keynesian models: Y = C + I Y = 0.75 Y + 75 Y - 0.75 Y = 75 (1 - .75) Y = 75 0.25Y = 75 multiply both sides by 4 Y = 4 * 75 = 300 billion Since the equilibrium GDP of 300 billion is higher than the actual GDP of 200 billion, we can forecast an increase in actual GDP (as long as the economy is not operating at capacity).