The Keynesian Theory of Determination of National Income

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Income Multiplier: Its Theory Its Philosophy Its Utility

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 The national income multiplier: Its theory its philosophy its utility John Colin Jones The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, John Colin, "The national income multiplier: Its theory its philosophy its utility" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8768. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8768 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NATIOHAL INCOME MULTIPLIER; ITS THEORY, ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS UTILITY J» COLIN H. JONES B.A. University of WaJes^ U.C.W., Aberystwyth, 195Ô Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by: , Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 6 1959 D a te UMI Number: EP39569 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dis»art«t)on Publishsng UMI EP39569 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

"Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-Based Multiplier Analysis"

Chapter 14 – Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-based Multiplier Analysis (Round) Chapter 14 Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-based Multiplier Analysis Jeffery Round1 14.1 Introduction This chapter sets out the framework of a social accounting matrix (SAM) and shows how it can be used to construct SAM-based multipliers to analyse the effects of macroeconomic policies on distribution and poverty. Estimates provided by a social accounting matrix (SAM) can be useful - even essential - for calibrating a much broader class of models to do with monitoring poverty and income distribution. But this chapter is limited to a review of how SAMs are used to develop simple economy-wide multipliers for poverty and income distribution analysis. What is a SAM? A SAM is a particular representation of the macro and meso economic accounts of a socio-economic system, which capture the transactions and transfers between all economic agents in the system (Pyatt and Round, 1985; Reinert and Roland-Holst, 1997). In common with other economic accounting systems it records transactions taking place during an accounting period, usually one year. The main features of a SAM are threefold. First, the accounts are represented as a square matrix; where the incomings and outgoings for each account are shown as a corresponding row and column of the matrix. The transactions are shown in the cells, so the matrix displays the interconnections between agents in an explicit way. Second, it is comprehensive, in the sense that it portrays all the economic activities of the system (consumption, production, accumulation and distribution), although not necessarily in equivalent detail. -

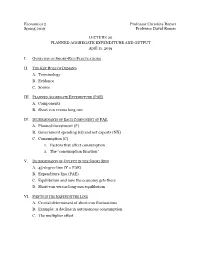

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

Circular Flow of Income Compiled from Internet

Circular flow of income Compiled from internet (not my own creation) The circular flow of income is a way of representing the flows of money between the two main groups in society - producers (firms) and consumers (households). These flows are part of the fundamental process of satisfying human wants. As we have already seen, a free market economy consists of two components, or sectors, as they are called. These are firms and households. People in households work for firms (selling their factor services) and receive wages in exchange. On the scale of the whole economy, this is known as national income - the total amount of income earned over a given time period. This money is spent on food, clothing, transport, entertainment etc, and so it returns to the firms. This is the circular flow. Figure 1 Circular flow of income We can see this circular flow in Figure 1. Households sell their factor services to firms (in the factor markets) and in exchange receive wages (the left-hand side of the flow). In the meantime, households spend this income on goods and services (in the goods market) and in exchange receive the goods and services themselves (the right-hand side of the flow). Economists call the wages plus the other forms of income, national income and give it the code 'Y'. Domestic consumption is given the code 'C'. Not all income is spent, however. Some is saved. Savings are coded as 'S'. Other money is used to buy goods or services produced overseas. The money to buy these goods and services flows out of the country. -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics -

12 Revision – National Income, Circular Flow, Multiplier

●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●● 12 Revision – National income, circular flow, multiplier The main economic goals There are usually five economic main aims for 2. A low level of unemployment government. 3. A low and stable rate of inflation 1. A steady rate of increase of national output 4. A favourable balance of payments position (economic growth) 5. An equitable distribution of income. The circular flow of income model Households INVESTMENT SAVING EXPORTS Expenditure Goods and Factors of Wages, rent, IMPORTS on goods and services production interest, and services profits GOVERNMENT Firms TAXES SPENDING Households provide the factors of production and 2. The income method measures the value of receive income. They buy the goods and services all the incomes earned in the economy. produced by the firms which use the income 3. The expenditure method measures the received, and in this way the income circulates value of all spending on goods and services in throughout the economy. the economy. This is calculated by summing The leakages from the system are savings, taxes up the spending by all the different sectors in and imports. The injections are investment, the economy. government spending and exports. The economy In practice, however, the data that is collected to is in equilibrium when leakages are equal to calculate each of the three values comes from injections. many different and varied sources, and inevitably there will be inaccuracies in the data, leading to imbalances among the final values. Measurement of national income Some of these inaccuracies are the result of the The most commonly used measure of a country’s timing of the data gathering; often figures have national income is gross domestic product (GDP). -

Coronavirus and the Effects on UK GDP

Article Coronavirus and the effects on UK GDP How the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the wider containment efforts are expected to impact on UK gross domestic product (GDP) as well as some of the challenges that National Statistical Institutes are likely to face. Contact: Release date: Next release: Sumit Dey-Chowdhury 6 May 2020 To be announced [email protected]. uk +44 (0)2075 928622 Table of contents 1. Executive summary 2. Background 3. The circular flow of income 4. The treatment of non-market output in GDP 5. The treatment of the CJRS and SEISS in GDP 6. Practical challenges 7. Publications 8. Conclusions 9. Authors Page 1 of 14 1 . Executive summary Forecasters expect the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to lead to a contraction in the UK and global economy this year, reflecting how it has led to a reduction in the demand for goods and services and the impact on the ability of businesses to supply those products. The impact is expected to reflect the length of the pandemic as well as the public health restrictions imposed and other voluntary social distancing measures. The response to COVID-19 will also impact on the ability of National Statistical Institutes (NSIs) to compile estimates of gross domestic product (GDP), inflation and the labour market. We are responding to these challenges so that we capture the economic activity of the UK in line with the latest international guidance. In this article, we describe how those transactions that are most likely to be impacted by the pandemic will be reflected in the production, income and expenditure measures of GDP ( Section 3), including how we have reflected this accordingly in our volume-based estimates of health and education output ( Section 4). -

Measuring Gdp and Economic Growth

MEASURING GDP Objectives AND ECONOMIC CHAPTER GROWTH 20 After studying this chapter, you will able to Define GDP and use the circular flow model to explain why GDP equals aggregate expenditure and aggregate income Explain the two ways of measuring GDP Explain how we measure real GDP and the GDP deflator Explain how we use real GDP to measure economic growth and describe the limitations of our measure © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 An Economic Barometer Gross Domestic Product GDP Defined What exactly is GDP GDP or gross domestic product, is the market value of How do we use it to tell us whether our economy is in a all final goods and services produced in a country in a recession or how rapidly our economy is expanding? given time period. How do we take the effects of inflation out of GDP to This definition has four parts: compare economic well-being over time Market value And how to we compare economic well-being across Final goods and services counties? Produced within a country In a given time period © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 Gross Domestic Product Gross Domestic Product Final goods and services Market value GDP is the value of the final goods and services produced. GDP is a market value—goods and services are valued at their market prices. A final good (or service), is an item bought by its final user during a specified time period. To add apples and oranges, computers and popcorn, we add the market values so we have a total value of output A final good contrasts with an intermediate good, which is in dollars. -

Macroeconomics II: the Circular Flow of Income

Macroeconomics II: The Circular Flow of Income Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret Hall Hilary Term 2004 introduction • “What is annually saved is as regularly consumed as what is annually spent, and nearly in the same time too; but it is consumed by a different set of people. That portion of his revenue which a rich man annually spends, is in most cases consumed by idle guests…That portion which he annually saves, as for the sake of the profit it is immediately employed as a capital, is consumed in the same manner…but by a different set of people”, Adam Smith, 1776. OECD macroeconomic performance OECD EU USA JAPAN GERMANY FRANCE ITALY UK Output Growth 1960-1973 4.9 4.7 4.0 9.7 4.3 5.4 5.3 3.1 1973-1979 3.2 2.6 2.9 3.5 2.4 2.7 3.5 1.5 1979-1989 2.9 2.2 2.8 3.8 2.0 2.1 2.4 2.4 1989-1999 2.6 2.0 3.0 1.7 2.2 1.7 1.3 1.9 Unemployment 1960-1973 2.9 2.6 4.8 1.2 1.0 2.6 5.7 3.3 1973-1979 5.0 4.6 6.7 1.9 3.0 4.4 6.0 4.9 1979-1989 7.3 9.4 7.3 2.5 5.8 8.8 8.2 9.8 1989-1999 7.4 9.9 5.8 3.1 7.5 11.2 10.9 8.3 Inflation 1960-1973 3.9 4.1 3.1 6.1 3.4 4.9 4.9 4.8 1973-1979 8.8 9.6 7.8 9.5 4.6 11.1 16.7 15.6 1979-1989 5.4 6.6 5.3 2.5 2.8 7.5 11.4 7.0 1989-1999 2.7 3.4 2.4 1.0 2.4 2.1 4.6 3.8 Source: Economics of the OECD 2000 exam paper data tables 1, 4 and 5. -

The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics

entropy Article The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics Aleksander Jakimowicz Department of World Economy, Institute of Economics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Palace of Culture and Science, 1 Defilad Sq., 00-901 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 13 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to examine the role of thermodynamics, and in particular, entropy, for the development of economics within the last 150 years. The use of entropy has not only led to a significant increase in economic knowledge, but also to the emergence of such scientific disciplines as econophysics, complexity economics and quantum economics. Nowadays, an interesting phenomenon can be observed; namely, that rapid progress in economics is being made outside the mainstream. The first significant achievement was the emergence of entropy economics in the early 1970s, which introduced the second law of thermodynamics to considerations regarding production processes. In this way, not only was ecological economics born but also an entropy-based econometric approach developed. This paper shows that non-extensive cross-entropy econometrics is a valuable complement to traditional econometrics as it explains phenomena based on power-law probability distribution and enables econometric model estimation for non-ergodic ill-behaved (troublesome) inverse problems. Furthermore, the entropy economics has accelerated the emergence of modern econophysics and complexity economics. These new directions of research have led to many interesting discoveries that usually contradict the claims of conventional economics. Econophysics has questioned the efficient market hypothesis, while complexity economics has shown that markets and economies function best near the edge of chaos. -

Economics 102 Fall 2015 Answers to Homework #5 Due December 14, 2015

Economics 102 Fall 2015 Answers to Homework #5 Due December 14, 2015 Directions: The homework will be collected in a box before the large lecture. Please place your name, TA name, and section number on the top of the homework (legibly). Make sure you write your name as it appears on your ID so that you can receive the correct grade. Late homework will not be accepted so make plans ahead of time. Please show your work. Good luck! Please realize that you are essentially creating “your brand” when you submit this homework. Do you want your homework to convey that you are competent, careful, professional? Or, do you want to convey the image that you are careless, sloppy, and less than professional. For the rest of your life you will be creating your brand: please think about what you are saying about yourself when you do any work for someone else! 1) Aggregate Consumption and Expenditure – The Keynesian Cross The following table gives some information regarding GDP, Consumption (C), Taxes (T), Transfers (TR), and Investment (I) in the autarkic (no imports or exports) nation of Haagland. Year GDP or Y C T TR G I 2014 $350 $200 $100 $50 $75 $200 2015 $450 $250 $100 $50 $75 $200 a) Given the above information, assuming that autonomous consumption and the marginal propensity to consume are constant, find an equation for consumption as a function of disposable income (Disposable Income = Yd = Y – (T – TR)). The fact that autonomous consumption and MPC are constant tells us that the consumption function is linear; thus, we need only identify two points that lie on the consumption function line to solve for the line.