Working Paper No. 134

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unemployment, Aggregate Demand, and the Distribution of Liquidity

Unemployment, Aggregate Demand, and the Distribution of Liquidity Zach Bethune Guillaume Rocheteau University of Virginia University of California, Irvine Tsz-Nga Wong Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond February 13, 2017 Abstract We develop a New-Monetarist model of unemployment in which distributional considerations matter. Households who lack commitment are subject to both employment and expenditure risk. They self- insure by accumulating real balances and, possibly, claims on firms profits. The distribution of liquidity is endogenous and responds to idiosyncratic risks and monetary policy. Despite the ex-post heterogeneity our model can be solved in closed form in a variety of cases. We show the existence of an aggregate demand channel according to which the distribution of workers across employment states, and their incomes in those states, affects the distribution of liquid wealth and firms’ profits. An increase in unemployment benefits or wages has a positive effect on aggregate demand and can lead to higher employment. Moreover, an increase in productivity has a multiplier effect on firms’ revenue. JEL Classification Numbers: D83 Keywords: unemployment, money, distribution. 1 Introduction We develop a New-Monetarist model of unemployment in which liquidity and distributional considerations matter. Our approach is motivated by the strong empirical evidence that household heterogeneity in terms of income and wealth, together with liquidity constraints, affect aggregate consumption and unemployment (e.g., Mian and Sufi, 2010?; Carroll et al., 2015). There is a recent literature that formalizes search frictions and liquidity constraints in goods markets that reduce the ability of firms to sell their output, their incentives to hire, and ultimately the level of unemployment (e.g., Berentsen, Menzio, and Wright, 2010; Michaillat and Saez, 2015). -

AS-AD and the Business Cycle

Chapter AS-AD and the Business Cycle CHAPTER OUTLINE 1. Provide a technical definition of recession and describe the history of the U.S. business cycle and the global business cycle. A. Dating Business-Cycle Turning Points B. U.S. Business-Cycle History C. Recent Cycles 2. Explain the influences on aggregate supply. A. Aggregate Supply Basics 1. Why the AS Curve Slopes Upward a. Business Failure and Startup b. Temporary Shutdowns and Restarts c. Changes in Output Rate 2. Production at a Pepsi Plant B. Changes in Aggregate Supply 1. Changes in Potential GDP 2. Changes in Money Wage Rate and Other Resource Prices 3. Explain the influences on aggregate demand. A. Aggregate Demand Basics 1. The Buying Power of Money 2. The Real Interest Rate 3. The Real Prices of Exports and Imports B. Changes in Aggregate Demand 1. Expectations 2. Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy 3. The World Economy C. The Aggregate Demand Multiplier 4. Explain how fluctuations in aggregate demand and aggregate supply create the business cycle. A. Aggregate Demand Fluctuations B. Aggregate Supply Fluctuations C. Adjustment Toward Full Employment 710 Part 10 . ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS CHAPTER ROADMAP What’s New in this Edition? Chapter 29 is now the first chapter in which the students en‐ counter the AS‐AD model. This chapter now uses some of the material from the second edition’s Chapter 23 introduc‐ tion to AS‐AD to explain the beginning about aggregate supply and aggregate demand. The connection between the AS‐AD model and business cycle has been rewritten and made even more straightforward for the students. -

Some Answers FE312 Fall 2010 Rahman 1) Suppose the Fed

Problem Set 7 – Some Answers FE312 Fall 2010 Rahman 1) Suppose the Fed reduces the money supply by 5 percent. a) What happens to the aggregate demand curve? If the Fed reduces the money supply, the aggregate demand curve shifts down. This result is based on the quantity equation MV = PY, which tells us that a decrease in money M leads to a proportionate decrease in nominal output PY (assuming of course that velocity V is fixed). For any given price level P, the level of output Y is lower, and for any given Y, P is lower. b) What happens to the level of output and the price level in the short run and in the long run? In the short run, we assume that the price level is fixed and that the aggregate supply curve is flat. In the short run, output falls but the price level doesn’t change. In the long-run, prices are flexible, and as prices fall over time, the economy returns to full employment. If we assume that velocity is constant, we can quantify the effect of the 5% reduction in the money supply. Recall from Chapter 4 that we can express the quantity equation in terms of percent changes: ΔM/M + ΔV/V = ΔP/P + ΔY/Y We know that in the short run, the price level is fixed. This implies that the percentage change in prices is zero and thus ΔM/M = ΔY/Y. Thus in the short run a 5 percent reduction in the money supply leads to a 5 percent reduction in output. -

Institutions, History and Wage Bargaining Outcomes: International Evidence from the Post-World War Two Era

Chris Minns and Marian Rizov Institutions, history and wage bargaining outcomes: international evidence from the post-World War Two era Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Minns, Chris and Rizov, Marian (2015) Institutions, history and wage bargaining outcomes: international evidence from the post-World War Two era. Business History, 57 (3). pp. 358-375. ISSN 0007-6791 DOI: 10.1080/00076791.2014.983480 © 2015 Taylor & Francis This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88847/ Available in LSE Research Online: June 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Institutions, History and Wage Bargaining Outcomes: International Evidence from the Post-World War Two Era Chris Minnsa and Marian Rizovb aDepartment of Economic History, London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Economics, Middlesex University Business School, London, United Kingdom (Submitted 29th September 2013; accepted 16 July 2014) Abstract This paper uses international evidence to assess the impact of tripartism and other forms of government involvement in bargaining on wage moderation and wage dispersion. -

Aggregate Demand and the Dynamics of Unemployment

Aggregate Demand and the Dynamics of Unemployment Edouard Schaal Mathieu Taschereau-Dumouchel New York University The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania June 3, 2016 Abstract We introduce an aggregate demand externality into the Mortensen-Pissarides model of equi- librium unemployment. Because firms care about the demand for their products, an increase in unemployment lowers the incentives to post vacancies which further increases unemploy- ment. This positive feedback creates a coordination problem among firms and leads to multiple equilibria. We show, however, that the multiplicity disappears when enough heterogeneity is introduced in the model. In this case, the unique equilibrium still exhibits interesting dynamic properties. In particular, the importance of the aggregate demand channel grows with the size and duration of shocks, and multiple stationary points in the dynamics of unemployment can exist. We calibrate the model to the U.S. economy and show that the mechanism generates ad- ditional volatility and persistence in labor market variables, in line with the data. In particular, the model can generate deep, long-lasting unemployment crises. JEL Classifications: E24, D83 1 1 Introduction The slow recovery that followed the Great Recession of 2007-2009 has revived interest in the long-held view in macroeconomics that episodes of high unemployment can persist for extended periods of time because of depressed aggregate demand. The mechanism seems intuitive: when firms expect lower demand for their products, they refrain from hiring and unemployment increases. In turn, as unemployment rises, aggregate income and spending decline, effectively confirming the low aggregate demand. In this paper, we propose a theory of unemployment and aggregate demand to investigate this mechanism. -

Wage Restraint, Employment, and the Legacy of the General Theory's

Wage Restraint, Employment, and the Legacy of the General Theory’s Chapter 19 Oliver Landmann University of Freiburg i.Br. 1. Introduction The role of wages in the determination of aggregate employment remains one of the most hotly debated public policy issues in many European countries, and in Germany in particular. This is not surprising in view of the high-profile collective bargaining process in which organized labor and employers negotiate over wages under conditions of persistent high unemployment. Of course, neither side wishes to be seen as merely pursuing its narrow self-interest. Both employers and unions make every effort to argue as convincingly as possible that their respective bargaining positions are conducive to employment growth and macroeconomic stability. Employers invoke neoclassical labor market theory to reject any demands for wage increases in excess of labor productivity growth. Such wage increases, they argue, mean rising labor costs and hence cause job losses. Unions, in contrast, emphasize demand-side repercussions and appeal to the keynesian notion of the circular flow of income. They maintain that any attempt to boost employment through wage restraint is doomed to fail, mainly because this would reduce the purchasing power of consumers and thus domestic demand. Accordingly, they tend to put the blame for high unemployment on misguided fiscal and monetary policies. In contrast, the mainstream consensus regards the longer-term trends of output and employment as supply-determined and, therefore, rejects demand-side explanations of unemployment, except for the very short-run cyclical movements. Keynes (1936) devoted an entire chapter of his General Theory, the famous Chapter 19, to the macroeconomic effects of changes in money-wages. -

Aggregate Supply and Unemployment

Aggregate Supply Explain why the elasticity of the aggregate supply curve for an economy varies between infinity and zero (12) Are supply-side policies likely to be more effective than demand-side policies in reducing unemployment? (13) Aggregate supply (AS) measures the output of goods and services than an economy can supply at a given price level in a given time period. The output potential of the economy depends on (a) the stock of factor inputs available (b) the productivity of factor inputs (c) the pace of technological progress. The elasticity of aggregate supply is a measure of how responsive output is to changes in demand. Supply elasticity normally depends on (a) the degree of spare capacity in the economy (b) the time period involved (c) the amount of stocks that can be used to meet changes in demand There is a continuing debate about the elasticity of aggregate supply. Standard Keynesian theory assumes a perfectly elastic aggregate supply curve. Changes in aggregate demand lead to changes in the equilibrium level of national output - prices are assumed to be constant in the injections and withdrawals framework. Neo- classical economists argue that aggregate supply in independent of the price level. The AS curve is assumed to be vertical in the long run - and can shift following increases in the stock and productivity of factors of production. A synthesis view shows the elasticity of aggregate supply changing at different levels of output. These views are shown in the diagrams below. Price Level (P) SRAS1 AD1 AD2 Y1 Y2 Real National Output (Y) In the diagram above the short run aggregate supply curve is drawn as perfectly elastic. -

Aggregate Demand by RENEE HALTOM

JARGONALERT Aggregate Demand BY RENEE HALTOM hat determines how much the economy pro- cycles but as a workable prescription for how policymakers duces in any given period? One way to think should respond to them. This backfired when attempts to Wabout it is through the concept of aggregate continually boost aggregate demand worked a little too well, demand, along with a partner concept, aggregate supply. resulting in inflation. The lesson was that the economy can’t An aggregate demand curve displays the quantity of goods be pushed beyond its sustainable level of supply for long. and services that are demanded at every possible price level in But many economists continue to argue that economists the economy. The aggregate quantity of goods and services should counteract demand shortfalls in recessions. This is demanded generally is high when prices are low and low when what the 2009 fiscal stimulus law tried to do. And in the prices are high (the opposite being true for aggregate supply, aftermath of the Great Recession, Christina Romer, then which slopes upward). Where the two intersect is, in theory, head of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, at the current level of gross domestic product (GDP). noted the presence of factors that Keynes might have agreed This theoretical framework can help economists think would be harmful to aggregate demand: a fall in wealth fol- through the causes of business cycles. For example, four com- lowing the 2007-2008 financial crisis, disruptions of credit, ponents of aggregate demand cause the aggregate demand shrinking government spending, and cautious spending from curve to shift outward when they increase: the amounts nervous consumers. -

Power, Platforms and the Free Trade Delusion

Trade and Development Report 2018: Power, Platforms and the Free Trade Delusion Addendum UNDERSTANDING THE GLOBAL ECONOMY ∗ WITH THE UN GLOBAL POLICY MODEL ∗ This UNCTAD Technical Addendum to the Trade and Development Report 2018: Power, Platforms and the Free Trade Delusion was prepared by external consultant Prof. Amitava Dutt (Department of Political Science, University of Notre Dame, USA and FLACSO-Ecuador), with guidance of UNCTAD’s Senior staff members. This paper has not been formally edited. - 1 - 1. Injections and leakages and financing For understanding the growth of an economy, it is useful to start with an accounting identity that shows how final production (net of intermediate goods that are used up in production) of a region, or its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is purchased by different sectors of the economy, that is, = + + + , where Y is total production, C is consumption, mostly purchased − by households, I is investment, mostly purchases by firms, G is government expenditure on goods and services, E is exports and M imports. This production identity shows that goods and services produced must end up as consumption, investment (which is mostly for adding to the stock of productive capital), government expenditure and exports, with imports subtracted because part of the first three items may represent purchases of what is produced abroad. The value of what is produced is equal to the value of income, and income can be consumed, saved, or taxed. From this we get the income identity = + + , where S is private saving and T is taxes (less transfers), we can use the production identity to get ( ) + ( ) + ( ) = 0, which we will refer to as the identity −. -

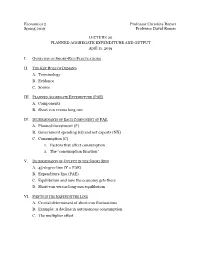

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

The Morale Effects of Pay Inequality

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE MORALE EFFECTS OF PAY INEQUALITY Emily Breza Supreet Kaur Yogita Shamdasani Working Paper 22491 http://www.nber.org/papers/w22491 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2016 We thank James Andreoni, Dan Benjamin, Stefano DellaVigna, Pascaline Dupas, Edward Glaeser, Robert Gibbons, Uri Gneezy, Seema Jayachandran, Lawrence Katz, Peter Kuhn, David Laibson, Ulrike Malmendier, Bentley MacLeod, Sendhil Mullainathan, Mark Rosenzweig, Bernard Salanie, and Eric Verhoogen for their helpful comments. Arnesh Chowdhury, Mohar Dey, Piyush Tank, and Deepak Saraswat provided outstanding research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge operational support from JPAL South Asia and financial support from the National Science Foundation, the IZA Growth and Labor Markets in Low Income Countries (GLM-LIC) program, and the Private Enterprise Development for Low Income Countries (PEDL) initiative. The project was registered in the AEA RCT Registry, ID 0000569. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2016 by Emily Breza, Supreet Kaur, and Yogita Shamdasani. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Morale Effects of Pay Inequality Emily Breza, Supreet Kaur, and Yogita Shamdasani NBER Working Paper No. 22491 August 2016 JEL No. -

Marx and Keynes: from Exploitation to Employment

Institute for International Political Economy Berlin Marx and Keynes: from exploitation to employment Author: Fritz Helmedag Working Paper, No. 113/2019 Editors: Sigrid Betzelt, Eckhard Hein (lead editor), Martina Metzger, Jennifer Pedussel Wu, Martina Sproll, Christina Teipen, Achim Truger, Markus Wissen, Reingard Zimmer Marx and Keynes: from exploitation to employment Fritz Helmedag* Abstract Marx’s and Keynes’s analyses of capitalism complement each other well. In a rather general model including the public sector and international trade it is shown that the labour theory of value provides a sound foundation to reveal the factors influencing employment. Workers buy ‘necessaries’ out of their disposa- ble wages from an integrated basic sector, whereas the ‘luxury’ department’s revenues spring from other sources of income. In order to maximize profits, the wage good industry controls the level of unit labour costs. After all, effective demand governs the volume of work. On this basis, implications for economic policy are outlined. JEL-classification: E11, E12, E24 Keywords: Employment, Marx, Keynes, Surplus value * Chemnitz University of Technology, Economics Department, Thüringer Weg 7, D-09107 Chemnitz, Germany. Email: [email protected] Paper presented at the IPE 10th Anniversary Conference: Studying Modern Capi- talism – The Relevance of Marx Today, Berlin, 12-13 July 2018. 2 Fritz Helmedag 1. Surplus value and the rate of profit The essence of this article is that the great economic thinkers mentioned in the title make a good couple not only regarding their exposure of capitalism’s mal- functions but also, and more importantly, from an analytical point of view.