Macroeconomics V: Aggregate Demand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 9 Keynesian Models of Aggregate Demand

Economics 314 Coursebook, 2010 Jeffrey Parker 9 KEYNESIAN MODELS OF AGGREGATE DEMAND Chapter 9 Contents A. Topics and Tools ............................................................................ 2 B. Comparative-Static Analysis of the Closed-Economy Basic Keynesian Model 3 Expenditure equilibrium and the IS curve ....................................................................... 4 Expenditures and the IS curve ....................................................................................... 5 Money demand and monetary policy.............................................................................. 7 The LM curve .............................................................................................................. 8 The MP curve .............................................................................................................. 9 Aggregate demand and aggregate supply ......................................................................... 9 C. Some Simple Aggregate-Supply Models ............................................... 10 Case 1: Nominal-wage stickiness .................................................................................. 11 Case 2: Inflation stickiness with competitive labor market ............................................... 12 Case 3: Inflation stickiness with labor-market imperfections ............................................ 13 Case 4: Sticky wages with imperfect competition ............................................................ 13 D. The Open Economy ....................................................................... -

Inventory Investment, Internal-Finance Fluctuations, and the Business Cycle

ROBERT E. CARPENTER Emory University STEVEN M. FAZZARI Washington University in St. Louis BRUCE C. PETERSEN Washington University in St. Lou is Inventory Investment, Internal-Finance Fluctuations, and the Business Cycle IT IS A well-known fact that inventory disinvestment can account for much of the movement in output during recessions. Almost one-half of the shortfall in output, averaged over the five interwar business cycles, can be accounted for by inventory disinvestment, and the proportion has been even larger for postwar recessions.' A lesser-known fact is that corporate profits, and therefore internal-finance flows, are also ex- tremely procyclical and tend to lead the cycle. Wesley Mitchell finds that the percentage change in corporate income over the business cycle is several times greater than that in any other macroeconomic series in his study.2 Robert Lucas lists the high conformity and large variation of corporate income as one of the seven main qualitative features of the business cycle.3 The volatility of internal finance, which is also com- We thank Lee Benham, Robert Chirinko, Mark Gertler, Simon Gilchrist, Edward Greenberg, Charles Himmelberg, Anil Kashyap, Louis Maccini, Dorothy Petersen, and Toni Whited for helpful comments, and Andrew Meyer, Bruce Rayton, and James Mom- tazee for excellent research assistance. Robert Parks and Daniel Levy provided technical assistance. We acknowledge financial support from the Jerome Levy Economics Institute, the University Research Committee of Emory University, and Washington University. 1. See Abramovitz (1950, p. 5) and Blinder and Maccini (199la). 2. Mitchell (1951, p. 286). These series include the rate of bankruptcy, employment, and pig iron production, among others. -

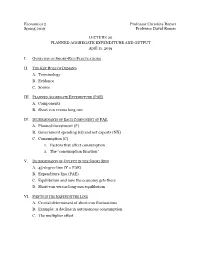

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

1 Keynesian Theory (IS-LM Model): How GDP and Interest Rates Are

Keynesian Theory (IS-LM Model): how GDP and interest rates are determined in Short Run with Sticky Prices. Historical background: The Keynesian Theory was proposed to show what could be done to shorten the Great Depression. key idea 1 is that during recessions producers have excessive capacity, they can supply any quantity at given price. That means the supply curve is flat (sticky price). In that case, the equilibrium quantity is determined by demand only. In other words, inadequate demand leads to insufficient quantity (recession). Recession can be avoided by increasing demand! Chapter 3: The Goods Market (Keynesian Cross) The key idea 2 is that, person A’s expenditure will become person B’s income, so B will spend, then person C’s income will rise, and C will spend, so on. In short, there are successive increases in output after someone spends. First of all, the aggregate demand for domestic goods can be decomposed as 푍 ≡ 퐶 + 퐼 + 퐺 + 푋 − 퐼푀 (푐표푛푠푢푚푝푡표푛 + 푛푣푒푠푡푚푒푛푡 + 푔표푣푒푟푛푚푒푛푡 푝푢푟푐ℎ푎푠푒 + 푒푥푝표푟푡 − 푚푝표푟푡) (1) This is an identity so we use ≡. In other words, such decomposition is always possible, see Table 3-1. Q1: which component will change if US government starts a new war against ISIS? Which component will be affected, in what way, by the fact that US dollar is appreciating? Next, we try to explain each component. For consumption, we let it be determined by disposable income. The consumption function is given by 퐶 = 퐶0 + 퐶1푌퐷 = 퐶0 + 퐶1(푌 − 푡푎푥 + 푡푟푎푛푠푓푒푟) (2) where 퐶0 is called _________________________________, and can be interpreted as___________________ 퐶1 is called _________________________________, and can be interpreted as___________________. -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

Mr. Keynes and the "Classics" Again: an Alternative Interpretation

Mr. Keynes and the "Classics" Again: An Alternative Interpretation David Colander Middlebury College It will be admitted by the least charitable reader that the textbook exposition of Keynesian economics and its integration with Classical economics are elegant. But it is also clear to most people who have read Keynes that the AS/AD textbook exposition of Keynesian economics embodies ideas that are not to be found in The General Theory, and includes others that Keynes went to great lengths to repudiate. In this paper I offer an alternative AS/AD exposition of Keynesian economics which better captures the essence of Keynes' ideas and offers a superior integration of Keynesian economics with Classical economics. The underlying ideas expressed in my alternative exposition are not original. They can be found, in varying degrees, in the work of Keynes, Don Patinkin, Abba Lerner, James Tobin, Paul Davidson, Robert Clower, Axel Leijonhufvud, and some of the New Keynesians, to mention only a few of those who have provided richer alternative interpretations of Keynesian economics. But these alternative interpretations are known primarily by macroeconomic and history of thought specialists. They have not become part of the standard core of macroeconomic theory as presented in the introductory and intermediate texts. Indeed, as I can testify to by experience, any attempt to include a discussion of these alternative interpretations in introductory or intermediate texts is met with great hostility by reviewers as being outside of the standard core. Despite the multitude of interpretations of Keynesian macroeconomics, only three have become part of the core of macroeconomics: Samuelson's Keynesian Cross, Hicks' IS/LM model, and a generic aggregate supply-demand model. -

Page 1 Econ 303: Intermediate Macroeconomics I Dr. Sauer

Econ 303: Intermediate Macroeconomics I Dr. Sauer Sample Questions for Exam #1 1. Variables that a model tries to explain are called: A) endogenous. B) exogenous. C) market clearing. D) fixed. 2. A measure of how fast prices are rising is called the: A) growth rate of real GDP. B) inflation rate. C) unemployment rate. D) market-clearing rate. 3. Deflation occurs when: A) real GDP decreases. B) the unemployment rate decreases. C) prices fall. D) prices increase, but at a slower rate. 4. A severe recession is called a(n): A) depression. B) deflation. C) exogenous event. D) market-clearing assumption. 5. The assumption of flexible prices is a more plausible assumption when applied to price changes that occur: A) from minute to minute. B) from year to year. C) in the long run. D) in the short run. 6. During the period between 1900 and 2000, the unemployment rate in the United States was highest in the: A) 1920s. B) 1930s. C) 1970s. D) 1980s. 7. The assumption of continuous market clearing means that: A) sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. B) buyers can buy all that they want at the going price. C) in any given month, buyers can buy all that they want and sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. D) at any given instant, buyers can buy all that they want and sellers can sell all that they want at the going price. 8. The total income of everyone in the economy adjusted for the level of prices is called: A) a recession. -

Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman Some Answers 1) A. During the Depression, the Federal Reserve Enacted Policies That Reduce

Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman Some Answers 1) a. During the Depression, the Federal Reserve enacted policies that reduced the money supply. Sketch a graph and on it indicate what this would do to the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves in the short run if output were originally at its natural level. What would happen to output and the aggregate price level in the short run? b. On the same graph, indicate what would happen to the short-run aggregate supply and aggregate demand curves over time if there were no further reductions in the money supply. Consequently, what would happen to output and price level over time? c. What is the final effect of this policy on output and the price level in the long run? Reduction of the money supply shifts the Aggregate Demand schedule and brings the economy from 1 to 2 in the short run. If the Fed does nothing else, the economy would find its way to 3 by a slow movement along the AD’ curve (or equivalently, shifts in the SRAS curve). The FINAL effect is no long run change in output, but a permanently lower price level. P LRAS 2 1 SRAS AD 3 AD’ Y Page 1 of 6 Problem Set 8 FE312 Fall 2011 Rahman 2) Throughout much of the 1990s, the United States experienced declining energy prices. Assume that the U.S. economy was in long-run equilibrium before these declines began. a. Use the aggregate demand-aggregate supply model to illustrate graphically the short-run AND long-run impact of this decline on output and prices. -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics -

Income and Expenditure

11 >>Income and Expenditure BE A PATRIOT AND SPEND FTER THE TERRORIST ATTACKS ON in recession, mainly because of a 14% drop ASeptember 11, 2001, many in real investment spending. A plunge in leading figures in American life consumer spending would have greatly made speeches urging the shocked nation deepened the recession. Fortunately, that to show fortitude—and keep buying con- didn’t happen: American consumers bought sumer goods. “Do your business around less of some goods and services, such as air the country. Fly and enjoy America’s great travel, but bought more of others. destination spots,” urged President Bush. As we explained in Chapter 10, the “Go shopping,” said former president source of most, but not all, recessions since Clinton. World War II has been negative demand chapter Such words were a far cry from British shocks, leftward shifts of the aggregate de- prime minister Winston Churchill’s famous mand curve. Over the course of this and What you will learn in 1940 declaration, in the face of an immi- the next three chapters, we’ll continue to this chapter: nent Nazi invasion of the United Kingdom, focus on the short-run behavior of the ® About consumption function, that he had nothing to offer but “blood, toil, economy, looking in detail at the factors which shows how disposable in- tears, and sweat.” But there was a reason that cause such shifts of the aggregate de- come affects consumer spending politicians of both parties called for spend- mand curve. In this chapter, we begin by ® How expected future income and ing, not sacrifice. -

Applying IS-LM Model in This Chapter We Learn the Potential Causes Of

Chapter 11: Applying IS-LM Model In this chapter we learn the potential causes of fluctuations in national income. We focus on demand shocks other than supply shocks. We also learn how the IS-LM model fits into the AD-AS model. Expansionary Fiscal Policy Suppose the government purchases rises by . If interest rate remains unchanged, from Keynesian cross we know the planned expenditure curve shifts (up down), and output (rises falls) by____________ Thus when goods market is in equilibrium, output rises for given interest rate. This implies that (IS LM) curve shifts (right left) But we have to take money market into account. Rising output will (increase decrease) the demand for real money balance. Since the supply of money remains fixed, interest rate must (rise fall) to clear the money market. That means we (move along shift) LM curve Finally we get Figure 11-1, which shows the effects of rising government purchase on output and interest rate, when both goods and money markets are in equilibrium. 1 Notice that interest rate (falls rises) and investment (falls rises). This fall in investment partially offsets the expansionary effect of the increase in government purchases. Thus, the increase in output in response to fiscal expansion is (bigger smaller) in the IS-LM model than it is in the Keynesian cross. This difference is explained by the crowding out of investment due to a higher interest rate. Expansionary Monetary Policy Suppose the money supply rises by . If output remains unchanged, then on the money market the money demand curve____________, and money supply curve ________________. -

A Review of Inventory Investment: the Macro and Micro Perspective

Journal of Financial Risk Management, 2016, 5, 57-62 Published Online March 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jfrm http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jfrm.2016.51007 A Review of Inventory Investment: The Macro and Micro Perspective Jianyu Huang Jinan University, Guangzhou, China Received 19 February 2016; accepted 28 March 2016; published 31 March 2016 Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article combed the domestic and foreign researches on inventory investment since 1990. We find that researches mainly focus on the macro level of the relationship between inventory in- vestment and business cycle, the effects of inflation or interest rates on inventory adjustment. While in the micro enterprise level, they study the determiners of inventory investment, including financing constraints, size and location. Besides, the role of inventory investment behavior on corporate performance has not yet reached a consensus. Based on the analysis of the existing lite- ratures, we put forward the possible directions for future research in the field of inventory in- vestment, combining with China’s specific conditions. Keywords Inventory Investment, Business Cycle, Influence Factors 1. Introduction Inventory is vital for both macro economy and micro enterprises. Accounting for less than 5% of the GDP fluc- tuation, inventory investment explains 20% of the production fluctuation. For the enterprise, inventory holding has both risks and opportunities. Too much inventory holding will generate storage cost and impairment loss, while little may not be able to meet the demand uncertainty in time and thus loss profit margins and market share.