Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Theories of Endogenous Growth

Economics 314 Coursebook, 2012 Jeffrey Parker 5 THEORIES OF ENDOGENOUS GROWTH Chapter 5 Contents A. Topics and Tools ............................................................................. 1 B. The Microeconomics of Innovation and Human Capital Investment ........... 3 Returns to research and development .............................................................................. 4 Human capital vs. knowledge capital ............................................................................. 6 Returns to education ..................................................................................................... 6 C. Understanding Romer’s Chapter 3 ....................................................... 9 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 The textbook’s modeling strategy and the research literature ............................................. 9 The basic setup of the R&D model ............................................................................... 10 The knowledge production function .............................................................................. 11 Analysis of the model without capital ........................................................................... 12 The R&D model with capital ...................................................................................... 16 Returns to scale and endogenous growth ....................................................................... 17 Scale effects in -

THE DEBATE of the MODERN THEORIES of REGIONAL ECONOMIC GROWTH Ra Ximhai, Vol

Ra Ximhai ISSN: 1665-0441 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México México Díaz-Bautista, Alejandro; González-Andrade, Salvador THE DEBATE OF THE MODERN THEORIES OF REGIONAL ECONOMIC GROWTH Ra Ximhai, vol. 10, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2014, pp. 187-206 Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México El Fuerte, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=46132135014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Ra Ximhai Revista de Sociedad, Cultura y Desarrollo Sustentable Ra Ximhai Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México ISSN: 1665-0441 México 2014 THE DEBATE OF THE MODERN THEORIES OF REGIONAL ECONOMIC GROWTH Alejandro Díaz-Bautista y Salvador González-Andrade Ra Ximhai, Julio - Diciembre, 2014/Vol. 10, Número 6 Edición Especial Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México Mochicahui, El Fuerte, Sinaloa. pp. 187 - 206 Ra Ximhai Vol. 10, Número 6 Edición Especial, Julio - Diciembre 2014 DEBATE EN LAS TEORÍAS MODERNAS DE CRECIMIENTO REGIONAL THE DEBATE OF THE MODERN THEORIES OF REGIONAL ECONOMIC GROWTH Alejandro Díaz-Bautista1 y Salvador González-Andrade2 1He is Professor of Economics and Researcher at the Department of Economic Studies, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF), he has also been a member of the United States - Mexico Border Governors Council of Economic Advisers. Email: [email protected]. 2He is Professor of Economics and Researcher at the Department of Economic Studies, COLEF. Email: [email protected] RESUMEN ¿Cómo podemos explicar las diferencias en el crecimiento económico en las distintas regiones del país y del mundo en los últimos sesenta años? El objetivo del estudio es el de realizar una revisión de la literatura tradicional de los principales modelos del crecimiento económico regional. -

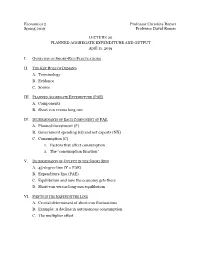

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE and OUTPUT Ap

Economics 2 Professor Christina Romer Spring 2019 Professor David Romer LECTURE 20 PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE AND OUTPUT April 11, 2019 I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS II. THE KEY ROLE OF DEMAND A. Terminology B. Evidence C. Source III. PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (PAE) A. Components B. Short run versus long run IV. DETERMINANTS OF EACH COMPONENT OF PAE p A. Planned investment (I ) B. Government spending (G) and net exports (NX) C. Consumption (C) 1. Factors that affect consumption 2. The “consumption function” V. DETERMINANTS OF OUTPUT IN THE SHORT RUN A. 45-degree line (Y = PAE) B. Expenditure line (PAE) C. Equilibrium and how the economy gets there D. Short-run versus long-run equilibrium VI. SHIFTS IN THE EXPENDITURE LINE A. Crucial determinant of short-run fluctuations B. Example: A decline in autonomous consumption C. The multiplier effect Economics 2 Christina Romer Spring 2019 David Romer LECTURE 20 Planned Aggregate Expenditure and Output April 11, 2019 Announcements • We have handed out Problem Set 5. • It is due at the start of lecture on Thursday, April 18th. • Problem set work session Monday, April 15th, 6:00–8:00 p.m. in 648 Evans. • Research paper reading for next time. • Romer and Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes.” I. OVERVIEW OF SHORT-RUN FLUCTUATIONS Real GDP in the United States, 1948–2018 Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data); data from Bureau of Economic Analysis. Short-Run Fluctuations • Times when output moves above or below potential (booms and recessions). • Recessions are costly and very painful to the people affected. Deviation of GDP from Potential and the Unemployment Rate Unemployment Rate Percent Deviation of GDP from Potential Source: FRED; data from Bureau of Labor Statistics. -

Endogenous Growth Theory: Intellectual Appeal and Empirical Shortcomings Author(S): Howard Pack Source: the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol

American Economic Association Endogenous Growth Theory: Intellectual Appeal and Empirical Shortcomings Author(s): Howard Pack Source: The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Winter, 1994), pp. 55-72 Published by: American Economic Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2138151 Accessed: 02/08/2010 15:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aea. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic Perspectives. http://www.jstor.org Journal of EconomicPerspectives- Volume 8, Number1-Winter 1994-Pages 55- 72 Endogenous Growth Theory: Intellectual Appeal and Empirical Shortcomings Howard Pack F ollowing along the path pioneered by Romer (1986) and Lucas (1988), endogenous growth theory has led to a welcome resurgence of interest in the determinants of long-term growth. -

DEVELOPMENT THEORY and the ECONOMICS of GROWTH Jaime

1 DEVELOPMENT THEORY AND THE ECONOMICS OF GROWTH Jaime Ros University of Notre Dame June 1999 DRAFT 2 Contents Introduction 1. The book’s aim and scope 2. Overview of the book 1. Some stylized facts 1. Incomes per capita across the world 2. Growth rates since 1965 Appendix 2. A mature economy: growth and factor accumulation 1. The Solow model 2. Empirical shortcomings 3. Extensions: technology and human capital 4. Endogenous investment rates Appendix 3. Labor surplus economies 1. The Lewis model 2. Are savings rates correlated with profit shares? 3. Surplus labor and the elasticity of labor supply 4. Efficiency wages and underemployment Appendix 4. Increasing returns, external economies, and multiple equilibria 3 1. Increasing returns to scale and efficiency wages 2. Properties and extensions 3. Empirical evidence Appendix 5. Internal economies, imperfect competition and pecuniary externalities 1. The big push in a multisectoral economy 2. Economies of specialization and a Nurksian trap 3. Vertical externalities: A Rodan-Hirschman model 6. Endogenous growth and early development theory 1. Models of endogenous growth 2. Empirical assessment 3. A development model with increasing returns and skill acquisition 7. Trade, industrialization, and uneven development 1. Openness and growth in the neoclassical framework 2. The infant industry argument as a case of multiple equilibria 3. Different rates of technical progress 4. Terms of trade and uneven development Appendix 8. Natural resources, the Dutch disease, and the staples thesis 1. On Graham's paradox 2. The Dutch disease under increasing returns 3. Factor mobility, linkages, and the staple thesis 4. An attempt at reconciliation: Two hybrid models Appendix 9. -

Chapter 5 Theories of Endogenous Growth

Economics 314 Coursebook, 2010 Jeffrey Parker 5 THEORIES OF ENDOGENOUS GROWTH Chapter 5 Contents A. Topics and Tools ............................................................................. 1 B. The Microeconomics of Innovation and Human Capital Investment ........... 3 Returns to research and development .............................................................................. 4 Human capital vs. knowledge capital ............................................................................. 6 Returns to education ..................................................................................................... 6 C. Understanding Romer=s Chapter 3, Part A ............................................. 9 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 Romer’s modeling strategy and the research literature ...................................................... 9 The basic setup of the R&D model ............................................................................... 10 The knowledge production function .............................................................................. 11 Analysis of the model without capital ........................................................................... 12 The R&D model with capital ...................................................................................... 16 Returns to scale and endogenous growth ....................................................................... 17 Scale effects in -

AGGREGATE DEMAND and ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, Et Al.), 2Nd Edition

Chapter 24 AGGREGATE DEMAND AND ECONOMIC FLUCTUATIONS Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin, et al.), 2nd Edition Chapter Overview This chapter first introduces the analysis of business cycles, and introduces you to the two stylized facts of the business cycle. The chapter then presents the Classical theory of savings-investment balance through the market for loanable funds. Next, the Keynesian aggregate demand analysis in the form of the traditional "Keynesian Cross" diagram is developed. You will learn what happens when there’s an unexpected fall in spending, and the role of the multiplier in moving to a new equilibrium. Chapter Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Describe how unemployment and inflation are thought to normally behave over the business cycle. 2. Model consumption and investment, the components of aggregate demand in the simple model. 3. Describe the problem that “leakages” present for maintaining aggregate demand, and the classical and Keynesian approaches to leakages. 4. Understand how the equilibrium levels of income, consumption, investment, and savings are determined in the Keynesian model, as presented in equations and graphs. 5. Explain how, in the Keynesian model, the macroeconomy can equilibrate at a less-than-full-employment output level. 6. Describe the workings of “the multiplier,” in words and equations. Key Terms Okun’s “law” behavioral equation “full-employment output” (Y*) marginal propensity to consume aggregate expenditure (AE) marginal propensity to save accounting identity paradox of thrift Chapter 24 – Aggregate Demand and Economic Fluctuations 1 Active Review Fill in the Blank 1. The macroeconomic goal that involves keeping the rate of unemployment and inflation at acceptable levels over the business cycle is the goal of . -

A Tale of Two Cities: Factor Accumulation and Technical Change in Hong Kong and Singapore

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1992, Volume 7 Volume Author/Editor: Olivier Jean Blanchard and Stanley Fischer, editors Volume Publisher: MIT Press Volume ISBN: 0-262-02348-2 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/blan92-1 Conference Date: March 6-7, 1992 Publication Date: January 1992 Chapter Title: A Tale of Two Cities: Factor Accumulation and Technical Change in Hong Kong and Singapore Chapter Author: Alwyn Young Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10990 Chapter pages in book: (p. 13 - 64) Alwyn Young SLOAN SCHOOLOF MANAGEMENT,MIT AND NBER A Tale of Two Cities: Factor Accumulation and Technical Change in Hong Kong and Singapore* 1. Introduction Recent years have witnessed an enormous revival of interest in growth theory, stimulated in no small part by the development of innovative models of endogenous growth by Romer (1986, 1990), Lucas (1988), Grossman and Helpman (1991a,b), Jones and Manuelli (1990), Rebelo (1991), and Stokey (1988). The empirical implications of these models have been subjected to extensive regression analysis using cross- national data sets (e.g., Barro 1991; Levine and Renelt 1991). Almost no attempt has been made, however, to link these new theories to the empirical experience of individual economies.1 Case study analyses pro- vide both the author and the reader with the opportunity to develop a rich understanding of the conditions, processes, and outcomes that have governed the growth experience of actual economies. As such, they provide a means of testing the implications of existing theories and developing one's thinking on the growth process. -

Growth in Overlapping Generation Economies with Non-Renewable Resources∗

Growth in Overlapping Generation Economies with Non-Renewable Resources∗ Betty Agnani, María-José Gutiérrez and Amaia Iza DFAEII - University of the Basque Country† September 2004 ∗We thank three anonymous referees, Jaime Alonso, Cruz Angel Echevarría, Tim Kehoe and Victor Rios-Rull for comments. Financial aid from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales and Universidad del País Vasco through projects SEC 2003-02510/ECO (Gutiérrez and Iza), CICYT 1393-12254/2000 (Agnani and Gutiérrez), BEC2000/1394 (Iza), MTAS 33/00 (Iza) and 9/UPV 00035.321- 13511/2001(Gutiérrez and Iza), respectively, and from Fundación BBVA is gratefully acknowledged. All errors are our own responsibility. †Correspondence to Universidad del País Vasco, Avda. Lehendakari Aguirre 83, 48015 Bilbao (Spain). Fax: 34-946013774. e-mail: [email protected] (Agnani), [email protected] (Gutiérrez) and jepiz- [email protected] (Iza). 1 Growth in Overlapping Generation Economies with Non-Renewable Resources ABSTRACT: Feasibility of positive steady-state growth in overlapping genera- tion (OLG) economies that use non-renewable resources as essential inputs in the production process is analyzed. The model we use is, in essence, that of Di- amond [9] with non-renewable resources and exogenous technological progress. The main finding is that having a high enough labor share is a necessary con- dition for the economy to exhibit positive steady-state growth rate. This condi- tion does not need to be satisfied in infinitely-lived agent economies. The reason is that although technological progress is introduced exogenously, in the OLG economy, the growth rate of the economy depends among others on capital ac- cumulation, which requires savings paid out of wage income. -

The Aggregate Expenditure Model a Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics

The Aggregate Expenditure Model A Stylized Look at Business Cycle Dynamics Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University Outline 1. The Aggregate Expenditure Model 2. An Expanded Aggregate Expenditure Model 3. The Multiplier Effect • Textbook Readings: Ch. 12 Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University From Macro Variables to (Short-Run) Macro Models • The first of three models - The Aggregate Expenditure Model § Solely output variables are in this model • Next class: Aggregate Demand - Aggregate Supply Model § Both output and prices are in this model • Later: Expanded Loanable Funds Model (Monetary Policy) § Output, prices and financial markets are in this model Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University A Quick Review • We have measurements GDP = C + I + G + NX § Consumption: Households purchases of goods and services § Investment: Housing, business investment in equipment, software, buildings plus inventories § Government spending: defense, infrastructure, social security, … § Net exports: Exports minus imports • We need a model § What forces drive the overall economy? Elements of Macroeconomics ▪ Johns Hopkins University What Are We Looking For With This Model? • We acknowledge that boom/bust cycles are regular occurrences • Periodically, we see big imbalances § Millions want jobs, but can’t find them ➞ Unemployment jumps § Millions want to drive cars and trucks ➞ Gasoline prices soar and inflation jumps • We want a model that identifies equilibrium, BUT ALLOWS FOR IMBALANCES Elements of Macroeconomics -

History, Microdata, and Endogenous Growth

EC11CH23_Akcigit ARjats.cls July 29, 2019 15:22 Annual Review of Economics History, Microdata, and Endogenous Growth Ufuk Akcigit1,2,3 and Tom Nicholas4 1Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA; email: [email protected] 2National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA 3Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, DC 20009, USA 4Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA; email: [email protected] Access provided by Harvard University on 09/10/19. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019. 11:615–33 Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019.11:615-633. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Keywords The Annual Review of Economics is online at economic development, growth, history, innovation economics.annualreviews.org https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics- Abstract 080218-030204 The study of economic growth is concerned with long-run changes, and Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. therefore, historical data should be especially influential in informing the All rights reserved development of new theories. In this review, we draw on the recent literature JEL Codes: O31, O38, O40 to highlight areas in which study of history has played a particularly promi- nent role in improving our understanding of growth dynamics. Research at the intersection of historical data, theory, and empirics has the potential to reframe how we think about economic growth in much the same way that historical perspectives helped to shape the first generation of endogenous growth theories. 615 EC11CH23_Akcigit ARjats.cls July 29, 2019 15:22 1. INTRODUCTION The study of history has been instrumental to the development of endogenous growth theory. -

Chapter 2 the AK Model

Chapter 2 The AK Model April 2, 2008 1 Introduction The neoclassical model presented in the previous chapter takes the rate of technological change as being determined exogenously, by non-economic forces. There is good reason, however, to believe that technological change depends on economic decisions, because it comes from industrial innovations made by profit-seeking firms, and depends on the funding of science, the accumulation of human capital and other such economic activities. Technology is thus an endogenous variable, determined within the economic system. Growth theories should take this endogeneity into account, especially since the rate of technological progress is what determines the long-run growth rate. Incorporating endogenous technology into growth theory forces us to deal with the diffi - cult phenomenon of increasing returns to scale. More specifically, people must be given an incentive to improve technology. But because the aggregate production function F exhibits constant returns in K and L alone, Euler’stheorem tells us that it will take all of the econ- omy’s output to pay capital and labor their marginal products in producing final output, leaving nothing over to pay for the resources used in improving technology.1 Thus a theory 1 Euler’s Theorem states that if F is homogeneous of degree 1 in K and L (the definition of constant returns) then F1 (K, L) K + F2 (K, L) L = F (K, L) (E) th where Fi is the partial derivative with respect to the i argument. The marginal products of K and L are F1 and F2 respectively. So if K and L are paid their marginal products then the left-hand side is the total payment to capital (price F1 times quantity K) plus the total payment to labor, and the equation states that these payments add up to total output.