Reconstructing the Fragmented Library of Mondsee Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Monastic History in Bookbinding Waste

Fragmentology A Journal for the Study of Medieval Manuscript Fragments Fragmentology is an international, peer-reviewed Open Access journal, dedicated to publishing scholarly articles and reviews concerning medieval manuscript frag- ments. Fragmentology welcomes submissions, both articles and research notes, on any aspect pertaining to Latin and Greek manuscript fragments in the Middle Ages. Founded in 2018 as part of Fragmentarium, an international research project at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, and the Zeno-Karl-Schindler Foun- dation, Fragmentology is owned and published by Codices Electronici AG and controlled by the Editorial Board in service to the scholarly community. Authors of articles, research notes, and reviews published in Fragmentology retain copyright over their works and have agreed to publish them in open access under a Creative Commons Attribution license. Submissions are free, and Fragmentology does not require payment or membership from authors or institutions. Editors: Christoph Flüeler (Fribourg) William Duba (Fribourg) Book Review Editor: Veronika Drescher (Fribourg/Paris) Editorial Board: Lisa Fagin Davis, (Boston, MA), Christoph Egger (Vienna), Thomas Falmagne (Frankfurt), Scott Gwara (Columbia, SC), Nicholas Herman (Philadelphia), Christoph Mackert (Leipzig), Marilena Maniaci (Cassino), Stefan Morent (Tübingen), Åslaug Ommundsen (Bergen), Nigel Palmer (Oxford) Instructions for Authors: Detailed instructions can be found at http://fragmen- tology.ms/submit-to-fragmentology/. Authors must agree to publish their work in Open Access. Fragmentology is published annually at the University of Fribourg. For further information, inquiries may be addressed to [email protected]. Editorial Address: Fragmentology University of Fribourg Rue de l’Hôpital 4 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland. -

Reconstructing the Fragmented Library of Mondsee Abbey

Reconstructing the Fragmented Library of Mondsee Abbey IVANA DOBCHEVA and VERONIKA WÖBER, Austrian National Library, Austria The Benedictine monastery of Mondsee was an important local centre for book production in Upper Austria already shortly after its foundation in 748. A central factor for the growth of the library were the monastic reform movements, which prompted the production of new liturgical books and consequently the discarding of older ones. When a bookbinding workshop was installed in the 15th century many of these manuscripts, regarded as useless, were cut up and re-used in bindings for new manuscripts, incunabula or archival materials. The aim of our two-year project funded by the Austrian Academy of Science (Go Digital 2.0) is to bring these historical objects in one virtual collection, where their digital facsimile and scholarly descriptions will be freely accessible online to a wide group of scholars from the fields of philology, codicology, history of the book and bookbinding. After a short glance at the history of Mondsee and the fate of the fragments in particular, this article gives an overview of the different procedures established in the project for the detecting and processing of the detached and in-situ fragments. Particular focus lays on the technical challenges encountered by the digitalisation, such as the work with small in-situ fragments partially hidden within the bookbinding. Discussed are also ways to address some disadvantages of digital facsimiles, namely the loss of information about the materiality of physical objects. Key words: Fragments, Manuscripts, Mondsee, Digitisation, Medieval library. CHNT Reference: Ivana Dobcheva and Veronika Wöber. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Books, Manuscripts and More for March 2020

Leo Cadogan March 2020 [email protected] LEO CADOGAN RARE BOOKS 74 Mayton Street, London N7 6QT BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS AND MORE FOR MARCH 2020 item 44 FARMING, WEATHER AND MEDICAL ADVICE FOR THE YEAR 1. Aicher, Otto, O.S.B.: Institutiones oeconomicae, sive discursus morales in duos libros Oeconomicorum Aristotelis, quibus omnia domesticae doctrinae, seu familiae regendae 1 Leo Cadogan March 2020 [email protected] elementa continentur. Accessit his liber III. de oeconomia in specie, quid quovis mense faciendum sit oeconomo. Salisburgi [Salzburg], typis Melchioris Hann 1690. 8vo. (14.8 cms. x 9.6 cms.), pp. [16] 223 [1]. Engraved extra title-page, featuring woman holding shovel (personification of Economy?), by J. Franck (possibly the German engraver Johann Franck - cf. Benezit). Light spotting and browning, very good, bound in brown morocco, decorated in gilt, arms at centre of front cover of Mondsee Abbey in Upper Austria, edges gilt, ties removed (worming to front cover, slightly rubbed). Inscription to verso of extra title-page, (Josephus ? Rysigger, professus Mondseensis, 1690), covered over with paper, a small seal applied to front pastedown, inscription to f.f.e.p. recto “Fran: Jac: Posch parochus in Ischl”. Finely-bound copy of the first edition of this handbook to household management, following the pseudo-Aristotelian work ‘Economics’. The book includes (126-223) a guide to the months of the year, with each month having a list of things to do on the farm, a list of rustic observations, which are largely concerned with the weather, and a list of medical observations. There are also general chapters on the times for sowing seed, instructions for what to do when the moon is in each sign of the Zodiac, and a list of rules for the farm manager. -

Fun in the Water for All the Family

The MondSeeLand, home to both the Mondsee and Irrsee lake, has been a popular holiday destination for decades. At just 27 km away from the festival city of Salzburg, international guests to the region can enjoy the many activities it has to offer. Fun in the water for all the family The Mondsee and Irrsee lakes are the warmest lakes in the Salzkammergut region and can reach temperatures of 27 °C in July and August. The Irrsee lake is very natural and ideal for all gentle water sports. The Mondsee lake plays host to numerous water sports activities such as surfing and sailing schools, wakeboarding, kite surfing, water skiing schools, diving schools, boat trips, diving, etc. The Mondsee is 11.8 km long and 2.5 km at its widest point. The Irrsee is 5 km long and 1 km at its widest point. Both lakes have excellent water quality. - 1 - Walking, cycling, running A high quality network of footpaths has been created around the Mondsee and Irrsee over the last few years, covering more than 100 km and leading to the neighbouring lakes – the Attersee, Fuschlsee and Wolfgangsee. A nature map of the MondSeeLand can be purchased from the tourist office (for 1 euro). This shows all the footpaths, cycle paths, jogging paths and specially designated relaxation areas. The cycle paths and footpaths are all well signposted and suitable for family days out. Meetings, congresses and company events The ‘Schloss Mondsee’ castle is home to a modern conference and events centre for hosting a variety of activities. International congresses and conferences of up to 500 participants are increasingly being held here, attracted by the fascination of the MondSeeLand, the good connection with the A1 motorway and the high quality historical atmosphere. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04210-0 — the Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West Volume 2 Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04210-0 — The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West Volume 2 Index More Information 1191 Index Aachen (chapel), 420 advocates, 859 – 61 Aachen, Synods of (816-819), 184 , 186 – 7 , 291 , lay nobility as, 581 , 585 323 , 375 , 387 , 422 , 424 , 438 – 41 , 455 , 462 , 482 , Áed mac Bricc of Rahugh, 301 497 – 8 , 508 – 9 , 526 Ælfric of Eynsham, 511 , 513 Aaron, Bishop of Kraków, 885 Colloquy , 415 Abelard, Peter, 652 , 675 , 682 , 697 , 735 , 740 , 741 , 743 , Aelred of Rievaulx, 573 , 721 , 751 , 753 , 756 777 , 967 , 1076 Rule for a Recluse , 753 , 759 Sic et Non, 458 Æthelwold of Winchester, 426 , 507 – 17 , Abbaye- aux- Dames of Saintes (monastery), 252 – 53 534 , 539 – 40 Abbo of Fleury, 595 , 627 Agaune, Life of the Abbots of , 61 Collectio , 6 2 1 , 6 2 7 Agaune, Saint- Maurice d’ (monastery), 37 , 116 , Abraham of Kaškar, 69 181 , 244 , 248 , 292 – 3 Abraham of Pboou/ Farshut, 54 Agde, Council of (506), 750 Abraham of Quiduna, Life of, 749 , 759 Agilulf, Lombard King, 238 Adalbero of Laon, Carmen ad Rotbertum Agnes of Antioch, 889 regem , 1157 Agnes of Babenberg, 889 Acemetes (monastery), 343 – 44 Agnes of Bohemia, 893 Acta Murensia , 5 7 2 Agnes of Hereford, 907 Acts of Paul and Thecla , 43 , 99 Agnes of Meissen (or Quedlinburg), 1004 Acts of Peter , 43 Agriculture, see also property and land Acts of the Apostles , 42 animal husbandry and pastoralism, 841 – 44 Acts of Thomas , 43 in Byzantium, 354 – 56 , see also property and land Adalard of Corbie, 460 , 472 cereal production, -

St. Pölten Abbey Was Founded Around 790 by the Bene 788 It Became an Imperial Benedictine Abbey

MigratiMigratioonn iinn thethe MiddlMiddlee Ages:Ages: ParasiteParasite stagesstages inin mmoonasterinasterialal latrinelatrine pits.pits. AndreasAndreas R.R. HasslHassl1,41,4,, AlicAlicee KKaaltenbergerltenberger22,, RonalRonaldd RisyRisy33 1 Institute of Specific Prophylaxis and Tropical Medicine, Center for Pathophysiology, Infectiology and Immunology, Medical University of Vienna 2 Institute of Archeologies, University of Innsbruck 3 Stadtarchäologie St. Pölten 4 MicroMicro--BBiiologologyy CCoonsultnsult Dr.Dr. AndAndrreaseas HasslHassl A fascinating aspect of archeomicrobiology is the evidence of endoparasitic diseases in long before deceased persons and domestic animals that can be revealed by studying well preserved excretions and that can elucidate everyday life of groups of people. During more recent archeological excavations in abandoned monasteries in Mondsee (Upper Austria) and St. Pölten (Lower Austria) well preserved refuse pits were discovered and the contents were scientifically processed in an interdisciplinary approach. Mondsee Abbey was founded in 748 by the Bavarian duke, in The St. Pölten abbey was founded around 790 by the Bene 788 it became an Imperial Benedictine abbey. 831 – 1142 it dictine abbey Tegernsee. After devastation it was repopulated was part of the monastery to Regensburg Cathedral. In 1506 by Canons Regular in 1081. In 1784 the abbey was dissolved, the possession passed from Bavaria to Austria. After a period but the buildings are used as the bishop seat of the diocese St. of decline during the Reformation, the abbey entered a second Pölten since 1785. period of prosperity, culminating in an extensive re-building of In the case of the abbey in St. the church and the monastic premises 1730 – 1770. In 1791 the abbey was dissolved. -

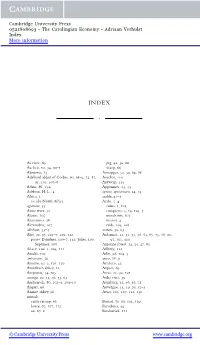

The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information INDEX . Aa river, 69 pig, 42, 50, 66 Aachen, 12, 34, 90–1 sheep, 66 Abruzzes, 13 Annappes, 32, 39, 64, 78 Adalhard abbot of Corbie, 60, 68–9, 75, 87, Anschar, 110 93, 101, 107–8 Antwerp, 134 Adam, H., 130 Appenines, 13, 35 Adelson, H. L., 4 aprisio, aprisionarii, 14, 53 Africa, 3 arable, 41–3 see also North Africa Arabs, 2–4 agrarium, 53 coins, 3, 105 Aisne river, 32 conquests, 3, 14, 103–5 Alcuin, 107 merchants, 105 Alemannia, 26 money, 4 Alexandria, 107 raids, 104, 108 allodium, 53–4 aratura, 50, 63 Alps, 92, 95, 104–7, 109, 112 Ardennes, 12, 34, 55, 58, 63, 65, 73, 76, 90, passes: Bundner,¨ 106–7, 112; Julier, 106; 97, 101, 110 Septimer, 106 Argonne forest, 34, 35, 47, 83 Alsace, 100–1, 109, 111 Arlberg, 112 Amalfi, 106 Arles, 98, 104–5 ambascatio, 50 arms, 78–9 Amiens, 92–3, 101, 130 Arnhem, 55 Amorbach abbey, 12 Arques, 69 Ampurias, 54, 105 Arras, 22, 90, 101 ancinga, 20, 43, 46, 55, 63 Aube river, 50 Andernach, 80, 102–3, 109–10 Augsburg, 42, 46, 56, 73 Angers, 98 Auvergne, 13, 19, 20, 52–3 Aniane abbey, 98 Avars, 105, 107, 112, 130 animals cattle raising, 66 Badorf, 79–80, 103, 109 horse, 67, 107, 112 Barcelona, 54 ox, 67–8 Bardowiek, 111 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information 152 Index Barisis, 82–3 carropera, 50 Bas-Languedoc, 19 carruca, 67 Bastogne, 90, 97 casata, 44 Bavaria, 32, 35, 42–3, 55–6, 82, 99, 105, castellum, -

Conference on Manuscript Studies 1974-2017

SAINT LOUIS CONFERENCE ON MANUSCRIPT STUDIES PROGRAMS 1974–2017 From 1974 to 2017 the Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies—which features papers on medieval and Renaissance manuscript studies, including such topics as paleography, codicology, illumination, text editing, library history, cataloguing, etc.—was organized and hosted by the Vatican Film Library at Saint Louis University. The conference continues and is now held under the auspices of the Saint Louis University Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies as part of its Annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 44th Conference (2017) pp. 3–14 43rd Conference (2016) pp. 15–26 42nd Conference (2015) pp. 27–38 41st Conference (2014) pp. 39–49 40th Conference (2013) pp. 50–60 39th Conference (2012) pp. 61–72 38th Conference (2011) pp. 73–84 37th Conference (2010) pp. 85–95 36th Conference (2009) pp. 96–107 35th Conference (2008) pp. 108–111 34th Conference (2007) pp. 112–115 33rd Conference (2006) pp. 116–119 32nd Conference (2005) pp. 120–123 31st Conference (2004) pp. 124–127 30th Conference (2003) pp. 128–130 29th Conference (2002) pp. 131–133 28th Conference (2001) pp. 134–137 27th Conference (2000) pp. 138–140 26th Conference (1999) pp. 141–143 25th Conference (1998) pp. 144–147 24th Conference (1997) pp. 148–151 23rd Conference (1996) pp. 152–155 22nd Conference (1995) pp. 156–159 21st Conference (1994) pp. 160–164 20th Conference (1993) pp. 165–167 19th Conference (1992) pp. 168–170 18th Conference (1991) pp. 171–174 17th Conference (1990) pp. 175–178 16th Conference (1989) pp. 179–182 15th Conference (1988) pp. -

Books and Libraries Within Monasteries Eva Schlotheuber and John T

975 53 Books and Libraries within Monasteries Eva Schlotheuber and John T. McQuillen (sections by Eva Schlotheuber translated by Eliza Jaeger) “One praises medieval libraries more than one knows them.” (Paul Lehmann) Books within the Monastery: A Tour To Jerome of Mondsee (d. 1475), master of the University of Vienna and pro- ponent of the Melk reform, the omnipresence of books within monasteries was self- evident. He expressed this sentiment in the title of his short work “Remarks that religious should have table readings, not only in the refectory, but also in other places (within the monastery).”1 Reading aloud was thought to make the contents of a text more accessible, individual reading to pro- mote introspection, and above all, to encourage compliance with the rule of silence, since reading aloud to one’s self was not the same as talking. Humbert of Romans (1200– 77), Dominican master general, wrote in his instructions for the various offices of the order that the librarian was to open the library regularly, but also to ensure that the books that most of the brothers did not personally possess were located in “appropriate places of silence,” usually chained to desks.2 Although the most extensive book collections were usually kept within the confines of the library, books could be found in many other places throughout the community. The early eighth-century Codex Amiatinus provides one of our ear- liest visualizations of a medieval book collection from a monastic setting. This manuscript was produced at the monastery of Wearmouth– Jarrow in Northumbria, but was based upon a sixth- century manuscript from Italy, the 1 Mittelalterliche Bibliothekskataloge Deutschlands und der Schweiz (hereafter MBK), 4 vols. -

BODY-SOUL DEBATES in ENGLISH, FRENCH and GERMAN MANUSCRIPTS C. 1200 - C

BODY-SOUL DEBATES IN ENGLISH, FRENCH AND GERMAN MANUSCRIPTS c. 1200 - c. 1500 Emily Jean Richards rk Centre for Medieval Studies April 2009 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the history of body-soul debates in English, Anglo-Nonnan, Northern French and Gennan from c.1200-1500. Focusing uniquely on the question of contexts rather than origins for the debates, I summarise their roots in apocryphal and pre-Christian myth before turning to close readings of the debates themselves and detailed examinations of their manuscripts. I argue that the various adaptations of the Latin 'Visio Philiberti' should be seen not only within the context of each language's vernacular literature, but also as a reaction to doctrinal changes in Christian theology during the period in which they were written. I also look at how these adaptations reflect the transmission of the debates by the religious orders, and examine the evidence for my argument that each body soul debate constructs specific paradigms of body and soul's relationship, focusing in particular on the differences between the hostile debates in England and France on the one side, and the 'friendly' debates in Gennany on the other. Finally, I examine parallel developments in the regulation of vernacular devotional literature in England, France and Germany in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, using a case study ofBL MS Additional 37049 to argue that these developments are reflected in more repressive and authoritarian adaptations of body-soul debates. Siting this hypothesis within the context of recent discussions of 'vernacular theology', I argue that body-soul debates functioned as literature which sanctioned authoritarian attitudes to vernacular literature and society, while at the same time presenting the possibility of a dialogic response to repressive measures and destabilising the topo; of obedience and subservience that they ostensibly support. -

Fairfield County Genealogy Society 1 Quarter NEWSLETTER

Volume 29 Number 1, 34th Year NEWSLETTER 1st Quarter 2018 Fairfield County Genealogy Society 1st Quarter NEWSLETTER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement ................................................................ .....................................................................2 Thank You Notes & Cards ................................................................ ...........................................................2 President’s Message ..................................................................................................................................3 History of Fairfield County's African Americans Program .............................................................................3 Volunteers Always Needed ........................................................................................................................4 Robert “Bob” Edward Killian, Sr. Obituary ..................................................................................................5 DNA Committee Report .............................................................................................................................5 Genealogy Resource Library 2017 Statistics ................................................................................................6 Cemetery Report .......................................................................................................................................7 Lowry Cemetery Visit ................................................................................................................................................