Berio Embraced Virtuosity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

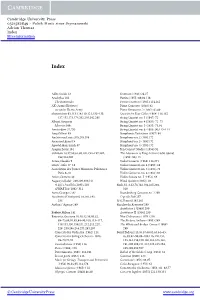

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

Developing Concepts of Musical Style

Durham E-Theses Developing concepts of musical style Marshall, Nigel Andrew How to cite: Marshall, Nigel Andrew (2001) Developing concepts of musical style, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3809/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham School of Education Developing concepts of musical style Nigel Andrew MarshaJJ 2001 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. This Thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy =- '1· JUN 2002 " .. .life is full of noise, death alone is silent: work Noise, noise of man, and noise of beast. Noise bought, sold or prohibited. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Review of Berio's Sequenzas

1 JMM – The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.7, Winter 2009. © JMM 7.7. http://www.musicandmeaning.net/issues/showArticle.php?artID=7.7 Halfyard, Janet, ed., Berio’s Sequenzas: Essays on Performance, Composition and Analysis (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). (Reviewed by Emma Gallon) 1 Berio’s Sequenzas (1958-2002) Although Berio has verified that the title Sequenza refers to the sequence of harmonic fields established by each of the series‟ fourteen works for a different solo instrument, the pieces are also united “by particular compositional aims and preoccupations – virtuosity, polyphony, the exploration of a specific instrumental idiom – applied to a series of different instruments”. (Janet Halfyard, “Forward” in Halfyard 2007: p.xx) These compositional aims in their various manifestations are explored in all of the essays in this book without exception, and both Berio‟s understanding of the terms, their relation to the pieces‟ signification and their implications for the receiver, be it performer, listener or analyst will be discussed below. Further details on Berio’s Sequenzas can be found on the Ashgate website at http://www.ashgate.com. The introduction to the book by the late David Osmond-Smith, leading authority on Berio and key in establishing Berio‟s reputation in Britain, focuses on the simultaneous musical commentary that the parallel Chemins series provides as the text of the Sequenza unfolds, and contrasts it with the difficult and almost prosaic retrospective commentaries that the musicologists in this book must undertake verbally in order to unweave the complex polyphonic strands of past echoes and present formations that Berio knots together. -

“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA “Sequenza I per flauto solo ” Luciano Berio Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter Alba María Jiménez Pérez Independent Project, Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Spring Semester. Year 2020 Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring Semester. Year 2020 Author: Alba María Jiménez Pérez Title: “Sequenza I per flauto solo . Luciano Berio. Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter” Supervisor: Johan Norrback Examiner: Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT This master thesis presents a comparison between the two versions of the piece Sequenza I for solo flute, written by Luciano Berio. Finding two editions of a piece with so different approach regarding the notation is not so common and understanding the process behind their composition is really important for its interpretation. Because of that, this thesis begins with the composer’s framework as well as the evolution of the piece composition and continues with the differences between both scores. The comparison has been done from a theoretical perspective, with the scores for reference as well as from an interpretative point of view. Finally, the author explains her own decisions and conclusions regarding the interpretation of the piece, obtained from this investigation. KEY WORDS: Berio, sequenza, flute, proportional notation, traditional rhythmic notation. INDEX Backround…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….5 Introduction and methodology…………………………………………………………..………..5 1. Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1 Sequences…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.2 Evolution of the Sequenza I………………………………………………….………. -

The King's Singers the King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 3-21-1991 Concert: The King's Singers The King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The King's Singers, "Concert: The King's Singers" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5665. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5665 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 THE KING'S SINGERS David Hurley, Countertenor Alastair Hume, Countertenor Bob Chilcott, Tenor Bruce Russell, Baritone Simon Carrington, Baritone Stephen Connolly, Bass I. Folksongs of North America THE FELLER FROM FORTUNE arranged by Robert Chilcott SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW I BOUGHT ME A CAT THE GIFT TO BE SIMPLE n. Great Masters of the English Renaissance Sacred Music from Tudor England TERRA TREMUIT William Byrd 0 LORD, MAKE THY SERVANT ELIZABETH OUR QUEEN (1543-1623) SING JOYFULLY UNTO GOD OUR STRENGTH AVE MARIA Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Ill. HANDMADE PROVERBS Toro Takemitsu (b. 1930) CRIES OF LONDON Luciano Berio (b. 1925) INTERMISSION IV. SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN OPERA Paul Drayton (b. 1944) v. Arrangements in Close Harmony Selections from the Lighter Side of the Repertoire Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, March 21, 1991 8:15 p.m. The King's Singers are represented by IMG Artists, New York. -

Thesis Submission

Rebuilding a Culture: Studies in Italian Music after Fascism, 1943-1953 Peter Roderick PhD Music Department of Music, University of York March 2010 Abstract The devastation enacted on the Italian nation by Mussolini’s ventennio and the Second World War had cultural as well as political effects. Combined with the fading careers of the leading generazione dell’ottanta composers (Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Ildebrando Pizzetti), it led to a historical moment of perceived crisis and artistic vulnerability within Italian contemporary music. Yet by 1953, dodecaphony had swept the artistic establishment, musical theatre was beginning a renaissance, Italian composers featured prominently at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse , Milan was a pioneering frontier for electronic composition, and contemporary music journals and concerts had become major cultural loci. What happened to effect these monumental stylistic and historical transitions? In addressing this question, this thesis provides a series of studies on music and the politics of musical culture in this ten-year period. It charts Italy’s musical journey from the cultural destruction of the post-war period to its role in the early fifties within the meteoric international rise of the avant-garde artist as institutionally and governmentally-endorsed superman. Integrating stylistic and aesthetic analysis within a historicist framework, its chapters deal with topics such as the collective memory of fascism, internationalism, anti- fascist reaction, the appropriation of serialist aesthetics, the nature of Italian modernism in the ‘aftermath’, the Italian realist/formalist debates, the contradictory politics of musical ‘commitment’, and the growth of a ‘new-music’ culture. In demonstrating how the conflict of the Second World War and its diverse aftermath precipitated a pluralistic and increasingly avant-garde musical society in Italy, this study offers new insights into the transition between pre- and post-war modernist aesthetics and brings musicological focus onto an important but little-studied era. -

The Full Concert Program and Notes (Pdf)

Program Sequenza I (1958) for fl ute Diane Grubbe, fl ute Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe Kyle Bruckmann, oboe O King (1968) for voice and fi ve players Hadley McCarroll, soprano Diane Grubbe, fl ute Matt Ingalls, clarinet Mark Chung, violin Erik Ulman, violin Christopher Jones, piano David Bithell, conductor Sequenza V (1965) for trombone Omaggio Toyoji Tomita, trombone Interval a Berio Laborintus III (1954-2004) for voices, instruments, and electronics music by Luciano Berio, David Bithell, Christopher Burns, Dntel, Matt Ingalls, Gustav Mahler, Photek, Franz Schubert, and the sfSound Group texts by Samuel Beckett, Luciano Berio, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Paul Griffi ths, Ezra Pound, and Eduardo Sanguinetti David Bithell, trumpet; Kyle Bruckmann, oboe; Christopher Burns, electronics / reciter; Mark Chung, violin; Florian Conzetti, percussion; Diane Grubbe, fl ute; Karen Hall, soprano; Matt Ingalls, clarinets; John Ingle, soprano saxophone; Christopher Jones, piano; Saturday, June 5, 2004, 8:30 pm Hadley McCarroll, soprano; Toyoji Tomita, trombone; Erik Ulman, violin Community Music Center Please turn off cell phones, pagers, and other 544 Capp Street, San Francisco noisemaking devices prior to the performance. Sequenza I for solo flute (1958) Sequenza V for solo trombone (1965) Sequenza I has as its starting point a sequence of harmonic fields that Sequenza V, for trombone, can be understood as a study in the superposition generate, in the most strongly characterized ways, other musical functions. of musical gestures and actions: the performer combines and mutually Within the work an essentially harmonic discourse, in constant evolution, is transforms the sound of his voice and the sound proper to his instrument; in developed melodically. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Friday Evening, December 1, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn, Mezzo-soprano Tengku Irfan, Piano Khari Joyner, Cello LUCIANO BERIO (1925–2003) Sequenza I (1958) GIORGIO CONSOLATI, Flute Folk Songs (1965–67) Black Is the Color I Wonder as I Wander Loosin yelav Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan Love Song KADY EVANYSHYN, Mezzo-soprano Intermission BERIO Sequenza XIV (2002) KHARI JOYNER, Cello “points on the curve to find…” (1974) TENGKU IRFAN, Piano Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program faith, in spite of it all, in the lingering pres- ence of the past. This gave his work a dis- by Matthew Mendez tinctly humanistic bent, and for all his experimental impulses, Berio’s relationship LUCIANO BERIO to the musical tradition was a cord that Born October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy never would be cut. Died May 27, 2003, in Rome, Italy Sequenza I In 1968 during his tenure on the Juilliard One way Berio’s interest in -

Luciano Berio's Sequenza V Analyzed Along the Lines of Four Analytical

Peer-Reviewed Paper JMM: The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.9, Winter 2010 Luciano Berio’s Sequenza V analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer Niels Chr. Hansen, Royal Academy of Music Aarhus, Denmark and Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK Abstract In this paper, Luciano Berio’s ‘Sequenza V’ for solo trombone is analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer himself in an interview from 1980. It is argued that the piece in general can be interpreted as an exploration of the ‘morphological’ dimension involving transformation of the traditional image of the trombone as an instrument as well as of the performance context. The first kind of transformation is revealed by simultaneous singing and playing, continuous sounds and considerable use of polyphony, indiscrete pitches, plunger, flutter-tongue technique, and unidiomatic register, whereas the latter manifests itself in extra-musical elements of theatricality, especially with reference to clown acting. Such elements are evident from performance notes and notational practice, and they originate from biographical facts related to the compositional process and to Berio’s sources of inspiration. Key topics such as polyphony, amalgamation of voice and instrument, virtuosity, theatricality, and humor – of which some have been recognized as common to the Sequenza series in general – are explained in the context of the analytical model. As a final point, a revised version of the four-dimensional model is presented in which tension-inducing characteristics in the ‘pitch’, ‘temporal’ and ‘dynamic’ dimensions are grouped into ‘local’ and ‘global’ components to avoid tension conflicts within dimensions.