Recital I (For Cathy): a Drama 'Through the Voice'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

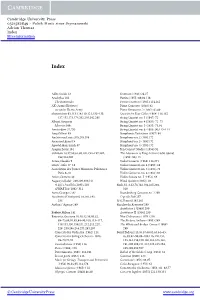

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

The Shaping of Time in Kaija Saariaho's Emilie

THE SHAPING OF TIME IN KAIJA SAARIAHO’S ÉMILIE: A PERFORMER’S PERSPECTIVE Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS May 2020 Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Brent E. Archer Graduate Faculty Representative Elaine J. Colprit Nora Engebretsen-Broman © 2020 Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor This document examines the ways in which Kaija Saariaho uses texture and timbre to shape time in her 2008 opera, Émilie. Building on ideas about musical time as described by Jonathan Kramer in his book The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies (1988), such as moment time, linear time, and multiply-directed time, I identify and explain how Saariaho creates linearity and non-linearity in Émilie and address issues about timbral tension/release that are used both structurally and ornamentally. I present a conceptual framework reflecting on my performance choices that can be applied in a general approach to non-tonal music performance. This paper intends to be an aid for performers, in particular conductors, when approaching contemporary compositions where composers use the polarity between tension and release to create the perception of goal-oriented flow in the music. iv To Adeli Sarasola and Denise Zephier, with gratitude. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the many individuals who supported me during my years at BGSU. First, thanks to Dr. Emily Freeman Brown for offering me so many invaluable opportunities to grow musically and for her detailed corrections of this dissertation. -

Melody Baggech, Fruit Bag, Babel, Credo for Plastical Score, Etc

Melody Baggech 2100 Fullview Drive, Ada, Oklahoma 74820 | (580) 235-5822 | [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE Professor of Voice – East Central University, 2018-present Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Associate Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2010-2018 Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera/Musical Theatre Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Assistant Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2001-2010 Private Studio Voice, Opera Theatre, Diction, Vocal Literature, Beginning Italian, Gospel Singers. Actively recruit and perform. Expanded existing opera program to include full-length performances and collaboration with ECU’s Theatre Department, local theatre companies and professional regional opera company. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Faculty, StartTalk Russian Language Camp, ECU 2012. Subjects taught: Russian folk song, Russian opera, Russian art song/poetry Adjunct Instructor of Voice, Panhandle State University, 1991-1993 Taught private studio voice, accompanied student juries. Performed in faculty recital series. Instructor of Voice, University of Oklahoma, March 20-April 27, 2000 Taught private studio voice to majors and non-majors. Private Studio Voice, Suburban Washington D.C., 2000-2001 Graduate Teaching Assistant, West Texas A&M University, 1988-1990 Voice Instructor, Moore High School, Moore, Oklahoma, 1998-1999 Voice Instructor, Travis Middle School, Amarillo, Texas, 1990-1991 EDUCATION DMA Vocal Performance, University of Oklahoma, 1998 Dissertation – An English Translation of Olivier Messiaen’s Traité de Rythme, de Couleur, et d’Ornithologie vol. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

The Full Concert Program and Notes (Pdf)

Program Sequenza I (1958) for fl ute Diane Grubbe, fl ute Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe Kyle Bruckmann, oboe O King (1968) for voice and fi ve players Hadley McCarroll, soprano Diane Grubbe, fl ute Matt Ingalls, clarinet Mark Chung, violin Erik Ulman, violin Christopher Jones, piano David Bithell, conductor Sequenza V (1965) for trombone Omaggio Toyoji Tomita, trombone Interval a Berio Laborintus III (1954-2004) for voices, instruments, and electronics music by Luciano Berio, David Bithell, Christopher Burns, Dntel, Matt Ingalls, Gustav Mahler, Photek, Franz Schubert, and the sfSound Group texts by Samuel Beckett, Luciano Berio, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Paul Griffi ths, Ezra Pound, and Eduardo Sanguinetti David Bithell, trumpet; Kyle Bruckmann, oboe; Christopher Burns, electronics / reciter; Mark Chung, violin; Florian Conzetti, percussion; Diane Grubbe, fl ute; Karen Hall, soprano; Matt Ingalls, clarinets; John Ingle, soprano saxophone; Christopher Jones, piano; Saturday, June 5, 2004, 8:30 pm Hadley McCarroll, soprano; Toyoji Tomita, trombone; Erik Ulman, violin Community Music Center Please turn off cell phones, pagers, and other 544 Capp Street, San Francisco noisemaking devices prior to the performance. Sequenza I for solo flute (1958) Sequenza V for solo trombone (1965) Sequenza I has as its starting point a sequence of harmonic fields that Sequenza V, for trombone, can be understood as a study in the superposition generate, in the most strongly characterized ways, other musical functions. of musical gestures and actions: the performer combines and mutually Within the work an essentially harmonic discourse, in constant evolution, is transforms the sound of his voice and the sound proper to his instrument; in developed melodically. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Friday Evening, December 1, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn, Mezzo-soprano Tengku Irfan, Piano Khari Joyner, Cello LUCIANO BERIO (1925–2003) Sequenza I (1958) GIORGIO CONSOLATI, Flute Folk Songs (1965–67) Black Is the Color I Wonder as I Wander Loosin yelav Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan Love Song KADY EVANYSHYN, Mezzo-soprano Intermission BERIO Sequenza XIV (2002) KHARI JOYNER, Cello “points on the curve to find…” (1974) TENGKU IRFAN, Piano Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program faith, in spite of it all, in the lingering pres- ence of the past. This gave his work a dis- by Matthew Mendez tinctly humanistic bent, and for all his experimental impulses, Berio’s relationship LUCIANO BERIO to the musical tradition was a cord that Born October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy never would be cut. Died May 27, 2003, in Rome, Italy Sequenza I In 1968 during his tenure on the Juilliard One way Berio’s interest in -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

El Lenguaje Musical De Luciano Berio Por Juan María Solare

El lenguaje musical de Luciano Berio por Juan María Solare ( [email protected] ) El compositor italiano Luciano Berio (nacido en Oneglia el 24 de octubre de 1925, muerto en Roma el 27 de mayo del 2003) es uno de los más imaginativos exponentes de su generación. Durante los años '50 y '60 fue uno de los máximos representantes de la vanguardia oficial europea, junto a su compatriota Luigi Nono, al alemán Karlheinz Stockhausen y al francés Pierre Boulez. Si lograron sobresalir es porque por encima de su necesidad de novedad siempre estuvo la fuerza expresiva. Gran parte de las obras de Berio ha surgido de una concepción estructuralista de la música, entendida como un lenguaje de gestos sonoros; es decir, de gestos cuyo material es el sonido. (Con "estructuralismo" me refiero aquí a una actitud intelectual que desconfía de aquellos resultados artísticos que no estén respaldados por una estructura justificable en términos de algún sistema.) Los intereses artísticos de Berio se concentran en seis campos de atención: diversas lingüísticas, los medios electroacústicos, la voz humana, el virtuosismo solista, cierta crítica social y la adaptación de obras ajenas. Debido a su interés en la lingüística, Berio ha examinado musicalmente diversos tipos de lenguaje: 1) Lenguajes verbales (como el italiano, el español o el inglés), en varias de sus numerosas obras vocales; 2) Lenguajes de la comunicación no verbal, en obras para solistas (ya sean cantantes, instrumentistas, actores o mimos); 3) Lenguajes musicales históricos, como -por ejemplo- el género tradicional del Concierto, típico del siglo XIX; 4) Lenguajes de las convenciones y rituales del teatro; 5) Lenguajes de sus propias obras anteriores: la "Sequenza VI" para viola sola (por ejemplo) fue tomada por Berio tal cual, le agregó un pequeño grupo de cámara, y así surgió "Chemins II". -

Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, Mezzo-Soprano" (2004)

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-17-2004 Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, mezzo- soprano Beth Alice Reichgott Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Reichgott, Beth Alice, "Junior Recital: Beth Alice Reichgott, mezzo-soprano" (2004). All Concert & Recital Programs. 3480. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/3480 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. JUNIOR RECITAL BETH ALICE REICHGOTT, mezzo-soprano Sean Cator, piano Assisted by: Leslie Lyons, violoncello and John Rozzoni, baritone HOCKETT FAMILY RECITAL HALL FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2004 7:00PM JUNIOR RECITAL BETH ALICE REICHGOTT, mezzo-soprano Sean Cator, piano Assisted by: Leslie Lyons, violoncello and John Rozzoni, baritone Vaga luna che inargenti Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) Bella Nice, che d' amore Per pieta, bell' idol mio Auf dem Wasser zu singen Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Du bist die Ruh Auf dem Strom Quando men vo Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) from La boheme INTERMISSION Must the winter come so soon? Samuel Barber (1910-1981) from Vanessa Une poupee aux yeux d'email Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) from Les contes d'Hoffmann Ariettes oubliees (1903) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) 2. I1 Pleure dans mon Coeur 3. L'Ombre des Arbres 4. Chevaux de Bois The Plough Boy Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) The trees they grow so high The Ash Grove Oliver Cromwell Baby, It's Cold Outside Frank Loesser (1910-1969) \ I r,' Junior Recital presented in partial fulfillment of a Bachelor's degree in Vocal Performance and Music Education. -

Dictionary of Music.Pdf

The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music Christine Ammer The Facts On File Dictionary of Music, Fourth Edition Copyright © 2004 by the Christine Ammer 1992 Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ammer, Christine The Facts On File dictionary of music / Christine Ammer.—4th ed. p. cm. Includes index. Rev. ed. of: The HarperCollins dictionary of music. 3rd ed. c1995. ISBN 0-8160-5266-2 (Facts On File : alk paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3009-5 (e-book) 1. Music—Dictionaries. 2. Music—Bio-bibliography. I. Title: Dictionary of music. II. Ammer, Christine. HarperCollins dictionary of music. III. Facts On File, Inc. IV. Title. ML100.A48 2004 780'.3—dc22 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by James Scotto-Lavino Cover design by Semadar Megged Illustrations by Carmela M. Ciampa and Kenneth L. Donlan Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise.” Copyright © 1960 Hinrichsen Edition, Peters Edition Limited, London. -

Music Theatre

11 Music Theatre In the 1950s, when attention generally was fi xed on musical funda- mentals, few young composers wanted to work in the theatre. Indeed, to express that want was almost enough, as in the case of Henze, to separate oneself from the avant-garde. Boulez, while earning his living as a theatre musician, kept his creative work almost entirely separate until near the end of his time with Jean-Louis Barrault, when he wrote a score for a production of the Oresteia (1955), and even that work he never published or otherwise accepted into his offi cial oeuvre. Things began to change on both sides of the Atlantic around 1960, the year when Cage produced his Theatre Piece and Nono began Intolleranza, the fi rst opera from inside the Darmstadt circle. However, opportunities to present new operas remained rare: even in Germany, where there were dozens of theatres producing opera, and where the new operas of the 1920s had found support, the Hamburg State Opera, under the direction of Rolf Liebermann from 1959 to 1973, was unusual in com- missioning works from Penderecki, Kagel, and others. Also, most com- posers who had lived through the analytical 1950s were suspicious of standard genres, and when they turned to dramatic composition it was in the interests of new musical-theatrical forms that sprang from new material rather than from what appeared a long-moribund tradition. (It was already a truism that no opera since Turandot had joined the regular international repertory. What was not realized until the late 1970s was that there could be a living operatic culture based on rapid obsolescence.) Meanwhile, Cage’s work—especially the piano pieces he 190 Music Theatre 191 had written for Tudor in the 1950s—had shown that no new kind of music theatre was necessary, that all music is by nature theatre, that all performance is drama.