Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice As Compositional Process in Berio's Sequenza I for Solo Flute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

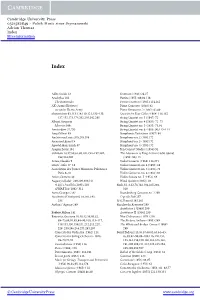

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

The Shaping of Time in Kaija Saariaho's Emilie

THE SHAPING OF TIME IN KAIJA SAARIAHO’S ÉMILIE: A PERFORMER’S PERSPECTIVE Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS May 2020 Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Brent E. Archer Graduate Faculty Representative Elaine J. Colprit Nora Engebretsen-Broman © 2020 Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor This document examines the ways in which Kaija Saariaho uses texture and timbre to shape time in her 2008 opera, Émilie. Building on ideas about musical time as described by Jonathan Kramer in his book The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies (1988), such as moment time, linear time, and multiply-directed time, I identify and explain how Saariaho creates linearity and non-linearity in Émilie and address issues about timbral tension/release that are used both structurally and ornamentally. I present a conceptual framework reflecting on my performance choices that can be applied in a general approach to non-tonal music performance. This paper intends to be an aid for performers, in particular conductors, when approaching contemporary compositions where composers use the polarity between tension and release to create the perception of goal-oriented flow in the music. iv To Adeli Sarasola and Denise Zephier, with gratitude. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the many individuals who supported me during my years at BGSU. First, thanks to Dr. Emily Freeman Brown for offering me so many invaluable opportunities to grow musically and for her detailed corrections of this dissertation. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique

The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique K J BALDWIN PHD 2020 The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique KERRY JANE BALDWIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by Manchester Metropolitan University 2020 CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Literature Review iii 1. 1900-1965 Historical Context: Influences on Sequenza V 1 a. Early Twentieth Century Developments 4 b. Glissando Techniques for Trombone 6 i. The False Glissando 6 ii. The Reverse Slide Glissando 10 c. Flutter Tongue 11 d. Theatrical Works 12 e. Berio & Grock 13 2. Performing Sequenza V 15 a. Introduction and Context b. Preparing to Learn Sequenza V 17 i. Instructions 17 ii. Equipment: Instrument 17 iii. Equipment: Mutes 18 iv. Equipment: Costume 19 c. Movement 20 d. Interpreting the Score 21 i. Tempo 21 ii. Notation 22 iii. Dynamics 24 iv. Muting 24 e. Sections A and B 26 f. WHY 27 g. The Third System 29 h. Multiphonics 31 i. Final Bar 33 j. The Sixth System 34 k. Further Vocal Pitches 35 l. Glissandi 36 m. Multiphonic Glissandi 40 n. Enharmonic Changes 44 o. Breathy Sounds 46 p. Flutter Tongue 47 q. Notable Performances of Sequenza V 47 i. Christian Lindberg 48 ii. Benny Sluchin 48 iii. Alan Trudel 49 3. 1966 – 2020 Historical Context: The Impact of Sequenza V 50 a. Techniques Repeated 50 b. Further Developments 57 c. -

Review of Berio's Sequenzas

1 JMM – The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.7, Winter 2009. © JMM 7.7. http://www.musicandmeaning.net/issues/showArticle.php?artID=7.7 Halfyard, Janet, ed., Berio’s Sequenzas: Essays on Performance, Composition and Analysis (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). (Reviewed by Emma Gallon) 1 Berio’s Sequenzas (1958-2002) Although Berio has verified that the title Sequenza refers to the sequence of harmonic fields established by each of the series‟ fourteen works for a different solo instrument, the pieces are also united “by particular compositional aims and preoccupations – virtuosity, polyphony, the exploration of a specific instrumental idiom – applied to a series of different instruments”. (Janet Halfyard, “Forward” in Halfyard 2007: p.xx) These compositional aims in their various manifestations are explored in all of the essays in this book without exception, and both Berio‟s understanding of the terms, their relation to the pieces‟ signification and their implications for the receiver, be it performer, listener or analyst will be discussed below. Further details on Berio’s Sequenzas can be found on the Ashgate website at http://www.ashgate.com. The introduction to the book by the late David Osmond-Smith, leading authority on Berio and key in establishing Berio‟s reputation in Britain, focuses on the simultaneous musical commentary that the parallel Chemins series provides as the text of the Sequenza unfolds, and contrasts it with the difficult and almost prosaic retrospective commentaries that the musicologists in this book must undertake verbally in order to unweave the complex polyphonic strands of past echoes and present formations that Berio knots together. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Fylkingen's Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974

Fylkingen’s Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974 Teddy Hultberg Abstract In the 1960s the concept and the genre of “text-sound composition” were born in Sweden. Being an offspring of sound poetry in various forms and of the new electro- acoustic music of the post-war years, it took shape as an intermedia art form par excel- lence. This essay traces the emergence of text-sound in a Swedish context and especially its appearance at the internationally renowned text-sound festivals held at Fylkingen in Stockholm during the years 1968–1974. By the time the term was invented in the 1960, text-sound composition, as an aesthetic practice, was already an international phenomenon. The Swedish version of this intermedia genre was given an international plat- form through the famous text-sound festivals that were organised by Fylkingen in Stockholm between 1968 and 1974. Founded as a chamber music society in 1933, Fylkingen had at this time developed into an organisa- tion that promoted all the new events in music, dance and theatre. And in this context sound poetry and text-sound composition appeared to be typi- cal art forms of the time – art forms that would explore the interstices between word and sound, poetry and music, and which would further the investigation of the electro-acoustic landscape staked out in avant-garde music from the post-war period by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luciano Berio. In short, the history of text-sound composition can be seen as the history of how technology during the early 1960s changed the poetic expression when it opened the literary field to a new kind of sound poetry. -

“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA “Sequenza I per flauto solo ” Luciano Berio Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter Alba María Jiménez Pérez Independent Project, Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Spring Semester. Year 2020 Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring Semester. Year 2020 Author: Alba María Jiménez Pérez Title: “Sequenza I per flauto solo . Luciano Berio. Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter” Supervisor: Johan Norrback Examiner: Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT This master thesis presents a comparison between the two versions of the piece Sequenza I for solo flute, written by Luciano Berio. Finding two editions of a piece with so different approach regarding the notation is not so common and understanding the process behind their composition is really important for its interpretation. Because of that, this thesis begins with the composer’s framework as well as the evolution of the piece composition and continues with the differences between both scores. The comparison has been done from a theoretical perspective, with the scores for reference as well as from an interpretative point of view. Finally, the author explains her own decisions and conclusions regarding the interpretation of the piece, obtained from this investigation. KEY WORDS: Berio, sequenza, flute, proportional notation, traditional rhythmic notation. INDEX Backround…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….5 Introduction and methodology…………………………………………………………..………..5 1. Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1 Sequences…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.2 Evolution of the Sequenza I………………………………………………….………. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

The King's Singers the King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 3-21-1991 Concert: The King's Singers The King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The King's Singers, "Concert: The King's Singers" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5665. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5665 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 THE KING'S SINGERS David Hurley, Countertenor Alastair Hume, Countertenor Bob Chilcott, Tenor Bruce Russell, Baritone Simon Carrington, Baritone Stephen Connolly, Bass I. Folksongs of North America THE FELLER FROM FORTUNE arranged by Robert Chilcott SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW I BOUGHT ME A CAT THE GIFT TO BE SIMPLE n. Great Masters of the English Renaissance Sacred Music from Tudor England TERRA TREMUIT William Byrd 0 LORD, MAKE THY SERVANT ELIZABETH OUR QUEEN (1543-1623) SING JOYFULLY UNTO GOD OUR STRENGTH AVE MARIA Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Ill. HANDMADE PROVERBS Toro Takemitsu (b. 1930) CRIES OF LONDON Luciano Berio (b. 1925) INTERMISSION IV. SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN OPERA Paul Drayton (b. 1944) v. Arrangements in Close Harmony Selections from the Lighter Side of the Repertoire Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, March 21, 1991 8:15 p.m. The King's Singers are represented by IMG Artists, New York.