“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Friday Evening, December 1, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn, Mezzo-soprano Tengku Irfan, Piano Khari Joyner, Cello LUCIANO BERIO (1925–2003) Sequenza I (1958) GIORGIO CONSOLATI, Flute Folk Songs (1965–67) Black Is the Color I Wonder as I Wander Loosin yelav Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan Love Song KADY EVANYSHYN, Mezzo-soprano Intermission BERIO Sequenza XIV (2002) KHARI JOYNER, Cello “points on the curve to find…” (1974) TENGKU IRFAN, Piano Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program faith, in spite of it all, in the lingering pres- ence of the past. This gave his work a dis- by Matthew Mendez tinctly humanistic bent, and for all his experimental impulses, Berio’s relationship LUCIANO BERIO to the musical tradition was a cord that Born October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy never would be cut. Died May 27, 2003, in Rome, Italy Sequenza I In 1968 during his tenure on the Juilliard One way Berio’s interest in -

Luciano Berio's Sequenza V Analyzed Along the Lines of Four Analytical

Peer-Reviewed Paper JMM: The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.9, Winter 2010 Luciano Berio’s Sequenza V analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer Niels Chr. Hansen, Royal Academy of Music Aarhus, Denmark and Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK Abstract In this paper, Luciano Berio’s ‘Sequenza V’ for solo trombone is analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer himself in an interview from 1980. It is argued that the piece in general can be interpreted as an exploration of the ‘morphological’ dimension involving transformation of the traditional image of the trombone as an instrument as well as of the performance context. The first kind of transformation is revealed by simultaneous singing and playing, continuous sounds and considerable use of polyphony, indiscrete pitches, plunger, flutter-tongue technique, and unidiomatic register, whereas the latter manifests itself in extra-musical elements of theatricality, especially with reference to clown acting. Such elements are evident from performance notes and notational practice, and they originate from biographical facts related to the compositional process and to Berio’s sources of inspiration. Key topics such as polyphony, amalgamation of voice and instrument, virtuosity, theatricality, and humor – of which some have been recognized as common to the Sequenza series in general – are explained in the context of the analytical model. As a final point, a revised version of the four-dimensional model is presented in which tension-inducing characteristics in the ‘pitch’, ‘temporal’ and ‘dynamic’ dimensions are grouped into ‘local’ and ‘global’ components to avoid tension conflicts within dimensions. -

HEKMAN, MARK P., D.M.A. Cross-Disciplinary Adaptation: a Training Plan for Luciano Berio's Sequenza XII. (2017) Directed by Dr

HEKMAN, MARK P., D.M.A. Cross-disciplinary Adaptation: A Training Plan for Luciano Berio’s Sequenza XII. (2017) Directed by Dr. Michael Burns. 42 pp. This paper applies macro concepts of athletic endurance training to music performance by adapting a running training plan into a multi-week bassoon practice sequence leading up to a musical goal. The adapted practice program reflects a training plan for an endurance athlete. The purpose is to examine if adopting an athletic-based approach can be helpful to musicians. The sequence was followed and the results show that specified practice programs can be beneficial in music pedagogy. CROSS-DISCIPLINARY ADAPTATION: A TRAINING PLAN FOR LUCIANO BERIO’S SEQUENZA XII by Mark P. Hekman A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2017 Approved by Committee Chair APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation, written by Mark P. Hekman, has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Committee Chair _______________________________ Committee Members _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date of Acceptance by Committee Date of Final Oral Examination ii PREFACE The key point leading to the hypothesis explored in this document is: A small adjustment in my approach to cycling training created exponential results and the positive effects of the experience continue to overwhelm me. I wanted to see if a similar approach could have similar benefits in musical performance. There was a window for fulfilling my childhood dream of becoming a professional cyclist which was closing. -

Towards a Precise Calculation of the Total Intended Duration of Luciano Berio’S Sequenza VII for Solo Oboe

Towards a Precise Calculation of the Total Intended Duration of Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII for Solo Oboe Olivier Paul Hal Barrier https://rcid.org/0000-0001-9446-8437 University of Pretoria, South Africa Clorinda Panebianco https://orcid.org/0000-0002-06370966X University of Pretoria, South Africa [email protected] Abstract The score of Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII for solo oboe exhibits a strict and definite temporal space, yet most performers do not manage to perform the work within the prescribed time. The score is presented as a matrix with thirteen lines and columns and each line undergoes a temporal compression. The impetus of this practitioner-based study was driven by a need to find a method of performing the unusual time increments and to be as close as possible to the composer’s intent regarding the temporal grid. The aim of this study was to investigate and demonstrate a method of calculating and performing the intended duration of Sequenza VII so that the performance realises the absolute duration intended by Berio. Two methods were used to calculate the total duration of the composition. The result of the precise calculation of the predetermined total duration of Sequenza VII is six minutes and thirty seconds, and therefore refines the results of previous explorations of this subject by other scholars. Keywords: oboe solo; Luciano Berio; Sequenza VII; empirical duration; “absolute” interpreta- tion; interpretivist perspective Introduction Vignette My first encounter with Sequenza VII started on the day that Luciano Berio passed away in 2003. The news was relayed over the radio. -

Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice As Compositional Process in Berio's Sequenza I for Solo Flute

Chapter 11 Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice as Compositional Process in Berio’s Sequenza I for Solo Flute Irna Priore The ideal listener is the one who can catch all the implications; the ideal composer is the one who can control them. Luciano Berio, 18 August 1995 Introduction Luciano Berio’s first Sequenza dates from 1958 and was written for the Italian flutist Severino Gazzelloni (1919–92). The first Sequenza is an important work in many ways. It not only inaugurates the Sequenza series, but is also the third major work for unaccompanied flute in the twentieth century, following Varèse’s Density 21.5 (1936) and Debussy’s Syrinx (1913).1 Berio’s work for solo flute is an undeniable challenge for the interpreter because it is a virtuoso piece, it is written in proportional notation without barlines, and it is structurally ambiguous.2 It is well known that performances of this piece brought Berio much dissatisfaction, a fact that led to the publication of a new version by Universal Edition in 1992.3 This new edition was intended to supply a metrical understanding of the work, apparently lacking or too vaguely implied in the original score. However, while some aspects of the piece have been clarified by Berio himself, 1 A three-note chromatic motif has been observed running as a unifying thread in all three works. See Cynthia Folio, ‘Luciano Berio’s Sequenza for Flute: A Performance Analysis’, The Flutist Quarterly, 15/4 (1990), p. 18. 2 The observations regarding the difficulty of the work were compiled from informal interviews conducted between autumn 2003 and spring 2004 with professionals teaching in American universities and colleges, to whom I am indebted. -

Luciano Berio's Sequenza

LUCIANO BERIO’S SEQUENZA III : THE USE OF VOCAL GESTURE AND THE GENRE OF THE MAD SCENE Patti Yvonne Edwards, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2004 APPROVED: Laurel Miller, Co-Major Professor Graham H. Phipps, Co-Major Professor and Director of Graduate Studies Jeffrey Snider, Committee Member and Chair of Vocal Studies James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Edwards, Patti Yvonne, Luciano Berio’s Sequenza III: The Use of Vocal Gesture and the Genre of the Mad Scene. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2004, 37 pp., references, 44 titles. Sequenza III was written in the mid -1960s and is widely available for study and performance, but how can this work be defined? Is it a series of sounds, or phonemes, or the anxious mutterings of a woman? Is it performance art or an operatic mad scene? Sequenza III could be all of these or something else entirely. Writing about my method of preparation will work to allay some of my own and other performer’s fears about attempting this unusual repertory. Very little in this piece is actually performed on pitch, and even then the pitches are not definite. The intervals on the five-line staff are to be observed but the singer may choose to sing within her own vocal range. The notation that Berio has used is new and specific, but the emotional markings and dynamics drawn from these markings permit a variety of interpretive decisions by the performer. -

Form and Virtuosity in Luciano Berio's Sequenza I

University of Alberta Form and Virtuosity in Luciano Berio's Sequenza I by Ian Knopke A thesis submitted to the Facuity of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Fa11 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Sireet 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Li'brary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnbute or seU reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. The objective of this thesis is an analysis of Luciano Berio's Sequenza I, for solo flute, using the composer's own published comments on the compositional system used in creating the piece. Additional insights into this system are provided by materials relating to an earlier composition, Nones, for orchestra. -

A Personal Experience

MASTERWORKS FOR BASS CLARINET – by Rocco Parisi hen the composer Saverio version of Paganini’s Capriccio 24 for violin. I Mercadante first met Catterino remember his gaze ranging between astonishment Catterini who played the glicibarifono and surprise, as if he was listening and seeing (the forefather of the modern bass something extraordinary. Some days later he phoned Wclarinet) in “La Fenice” Theater Orchestra in Venice, me, asking if I was available to work with him on a he immediately became fascinated by this instrument bass clarinet version of his Sequenza IXa for clarinet. and recognized its great potential. Mercadante was The main theme of every Berio Sequenza for so moved by Catterini’s virtuosity that he wrote solo instrument is the required virtuosity both in conceptual and technical aspects. These were the a solo for him in the opera Emma di Antiochia, elements that really amazed Berio in my version commissioned for the 1834 carnival season and of Paganini’s Capriccio 24. I worked with him for played in March of the same year. This is the first four days in his house in Florence in 1997. He solo ever written for bass clarinet. was fascinated by the versatility of my bass clarinet Emma di Antiochia was considered a masterpiece. playing and loved the low sounds and high sounds at This solo impressed and interested critics of the the same time. These are the parameters that inspired day who referred to the bass clarinet sound as “voce the new version, Sequenza IXc for bass clarinet. del clarinetto e insieme del fagotto vale a dire che Compared with the previous version for clarinet, ha le note dell’uno e dell’altro” (like the sound of a everything has been shifted down by a 10th and clarinet and a bassoon at the same time). -

Tempo Ligeti the Postmodernist?

Tempo http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM Additional services for Tempo: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Ligeti the Postmodernist? Mike Searby Tempo / Issue 199 / January 1997, pp 9 15 DOI: 10.1017/S0040298200005544, Published online: 23 November 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0040298200005544 How to cite this article: Mike Searby (1997). Ligeti the Postmodernist?. Tempo, pp 915 doi:10.1017/S0040298200005544 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM, IP address: 141.241.166.121 on 25 Apr 2013 Mike Searby Ligeti the Postmodernist? The stylistic changes in Gyorgy Ligeti's music eminent influence on Ligeti in his formative years: since 1960 have in some ways mirrored those in Bartok remained my idol until 1950, and he continued the wider contemporary music world. In his to be very important [to] me even after I left the music of the 1960s he displays an experimental country in 1956.4 and systematic approach to the exploration of sound matter which can also be seen in the Ligeti himself considers that Bartok's influence contemporaneous music of composers such as has returned in his music: Xenakis, Penderecki and Stockhausen. In the Ever since the 1980s I have experienced a kind of 1970s his music shows a more eclectic approach, return to Bartok, especially as far as the Piano particularly the opera Le Grand Macabre (1974-7) Concerto is concerned.5 in which there is much plundering of past styles - The resulting music, however, is very different to such as allusions to Monteverdi, Rossini, and his Bartok-tinged music of the 1950s because it Verdi. -

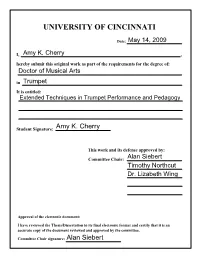

Extended Techniques in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 14, 2009 I, Amy K. Cherry , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Trumpet It is entitled: Extended Techniques in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy Student Signature: Amy K. Cherry This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Alan Siebert Timothy Northcut Dr. Lizabeth Wing Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Alan Siebert Extended Techniques in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy a document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Division of the CollegeǦConservatory of Music 2009 by Amy K. Cherry B.M., University of Illinois, 1993 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1995 Committee Chair: Alan Siebert ABSTRACT The impetus for this study was the question of whether extended techniques are actually being taught in college trumpet studio settings as standard skills necessary on the instrument. The specific purposes of this document included: 1) catalogue the extended techniques available to today’s trumpet performer, 2) reflect on their current use and address the question of how and when students are introduced to extended techniques, 3) contribute pedagogical exercises and suggestions to aid trumpeters in the study of some of the more challenging techniques, and 4) conclude with a Guided Approach to the literature detailing suggestions for the study of the twenty pieces referenced in this document.