Towards a Precise Calculation of the Total Intended Duration of Luciano Berio’S Sequenza VII for Solo Oboe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

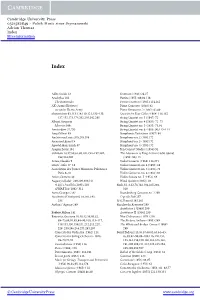

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Invenzione Festival Berio

INVENZIONE FESTIVAL BERIO Du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 www.cnsmd-lyon.fr , Paris DES SIGNES DES : conception graphique conception Invenzione festival Berio du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 La musique n’est pas pressée : elle vit dans notre culture, le temps des arbres et des forêts, de la mer et des grandes villes. Luciano Berio Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Luciano Berio a marqué pour toujours la musique de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Son œuvre, sans frontières et d’une incroyable diversité, a mis à profit toutes les techniques, du sérialisme à l’électroacoustique. L’homme ne s’est laissé enfermer dans aucun clan, parti pris théorique ou gratuité abstraite. Son intelligence prend appui sur la vie, un esprit d’invention et une imagination généreuse. Il réinventa les continuités en gardant une curiosité insatiable pour les expériences exploratoires. Ses dialogues avec littérature, linguistique, anthropologie ou ethnomusicologie ont nourri son inventivité et c’est en tant que compositeur qu’il s’est approprié les matières qui le fascinaient afin d’en extraire des effets parfois fort éloignés de leur contexte d’origine. Berio a aussi sondé des domaines originaux et longtemps oubliés de notre culture occidentale, en particulier celui de la voix féminine qui a pris de plus en plus de place dans ses œuvres ; le chant impliquant un texte, Berio a collaboré avec des poètes tels que Sanguineti. Passionné par le potentiel des timbres instrumentaux, il a écrit une vaste série de pièces pour instruments solo, les fameuses Sequenza, puis s’est attaché dès les années 60 à explorer les plus improbables combinaisons de timbres. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique

The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique K J BALDWIN PHD 2020 The Influence of Berio Sequenza V on Trombone Repertoire and Technique KERRY JANE BALDWIN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by Manchester Metropolitan University 2020 CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Literature Review iii 1. 1900-1965 Historical Context: Influences on Sequenza V 1 a. Early Twentieth Century Developments 4 b. Glissando Techniques for Trombone 6 i. The False Glissando 6 ii. The Reverse Slide Glissando 10 c. Flutter Tongue 11 d. Theatrical Works 12 e. Berio & Grock 13 2. Performing Sequenza V 15 a. Introduction and Context b. Preparing to Learn Sequenza V 17 i. Instructions 17 ii. Equipment: Instrument 17 iii. Equipment: Mutes 18 iv. Equipment: Costume 19 c. Movement 20 d. Interpreting the Score 21 i. Tempo 21 ii. Notation 22 iii. Dynamics 24 iv. Muting 24 e. Sections A and B 26 f. WHY 27 g. The Third System 29 h. Multiphonics 31 i. Final Bar 33 j. The Sixth System 34 k. Further Vocal Pitches 35 l. Glissandi 36 m. Multiphonic Glissandi 40 n. Enharmonic Changes 44 o. Breathy Sounds 46 p. Flutter Tongue 47 q. Notable Performances of Sequenza V 47 i. Christian Lindberg 48 ii. Benny Sluchin 48 iii. Alan Trudel 49 3. 1966 – 2020 Historical Context: The Impact of Sequenza V 50 a. Techniques Repeated 50 b. Further Developments 57 c. -

Review of Berio's Sequenzas

1 JMM – The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.7, Winter 2009. © JMM 7.7. http://www.musicandmeaning.net/issues/showArticle.php?artID=7.7 Halfyard, Janet, ed., Berio’s Sequenzas: Essays on Performance, Composition and Analysis (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007). (Reviewed by Emma Gallon) 1 Berio’s Sequenzas (1958-2002) Although Berio has verified that the title Sequenza refers to the sequence of harmonic fields established by each of the series‟ fourteen works for a different solo instrument, the pieces are also united “by particular compositional aims and preoccupations – virtuosity, polyphony, the exploration of a specific instrumental idiom – applied to a series of different instruments”. (Janet Halfyard, “Forward” in Halfyard 2007: p.xx) These compositional aims in their various manifestations are explored in all of the essays in this book without exception, and both Berio‟s understanding of the terms, their relation to the pieces‟ signification and their implications for the receiver, be it performer, listener or analyst will be discussed below. Further details on Berio’s Sequenzas can be found on the Ashgate website at http://www.ashgate.com. The introduction to the book by the late David Osmond-Smith, leading authority on Berio and key in establishing Berio‟s reputation in Britain, focuses on the simultaneous musical commentary that the parallel Chemins series provides as the text of the Sequenza unfolds, and contrasts it with the difficult and almost prosaic retrospective commentaries that the musicologists in this book must undertake verbally in order to unweave the complex polyphonic strands of past echoes and present formations that Berio knots together. -

“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA “Sequenza I per flauto solo ” Luciano Berio Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter Alba María Jiménez Pérez Independent Project, Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Spring Semester. Year 2020 Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring Semester. Year 2020 Author: Alba María Jiménez Pérez Title: “Sequenza I per flauto solo . Luciano Berio. Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter” Supervisor: Johan Norrback Examiner: Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT This master thesis presents a comparison between the two versions of the piece Sequenza I for solo flute, written by Luciano Berio. Finding two editions of a piece with so different approach regarding the notation is not so common and understanding the process behind their composition is really important for its interpretation. Because of that, this thesis begins with the composer’s framework as well as the evolution of the piece composition and continues with the differences between both scores. The comparison has been done from a theoretical perspective, with the scores for reference as well as from an interpretative point of view. Finally, the author explains her own decisions and conclusions regarding the interpretation of the piece, obtained from this investigation. KEY WORDS: Berio, sequenza, flute, proportional notation, traditional rhythmic notation. INDEX Backround…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….5 Introduction and methodology…………………………………………………………..………..5 1. Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1 Sequences…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.2 Evolution of the Sequenza I………………………………………………….………. -

The Full Concert Program and Notes (Pdf)

Program Sequenza I (1958) for fl ute Diane Grubbe, fl ute Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe Kyle Bruckmann, oboe O King (1968) for voice and fi ve players Hadley McCarroll, soprano Diane Grubbe, fl ute Matt Ingalls, clarinet Mark Chung, violin Erik Ulman, violin Christopher Jones, piano David Bithell, conductor Sequenza V (1965) for trombone Omaggio Toyoji Tomita, trombone Interval a Berio Laborintus III (1954-2004) for voices, instruments, and electronics music by Luciano Berio, David Bithell, Christopher Burns, Dntel, Matt Ingalls, Gustav Mahler, Photek, Franz Schubert, and the sfSound Group texts by Samuel Beckett, Luciano Berio, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Paul Griffi ths, Ezra Pound, and Eduardo Sanguinetti David Bithell, trumpet; Kyle Bruckmann, oboe; Christopher Burns, electronics / reciter; Mark Chung, violin; Florian Conzetti, percussion; Diane Grubbe, fl ute; Karen Hall, soprano; Matt Ingalls, clarinets; John Ingle, soprano saxophone; Christopher Jones, piano; Saturday, June 5, 2004, 8:30 pm Hadley McCarroll, soprano; Toyoji Tomita, trombone; Erik Ulman, violin Community Music Center Please turn off cell phones, pagers, and other 544 Capp Street, San Francisco noisemaking devices prior to the performance. Sequenza I for solo flute (1958) Sequenza V for solo trombone (1965) Sequenza I has as its starting point a sequence of harmonic fields that Sequenza V, for trombone, can be understood as a study in the superposition generate, in the most strongly characterized ways, other musical functions. of musical gestures and actions: the performer combines and mutually Within the work an essentially harmonic discourse, in constant evolution, is transforms the sound of his voice and the sound proper to his instrument; in developed melodically. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

The Digital Concert Hall

Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall he time has finally come! Four years have Emmanuelle Haïm, the singers Marlis Petersen passed since the Berliner Philharmoniker – the orchestra’s Artist in Residence – Diana T elected Kirill Petrenko as their future chief Damrau, Elīna Garanča, Anja Kampe and Julia conductor. Since then, the orchestra and con- Lezhneva, plus the instrumentalists Isabelle ductor have given many exciting concerts, fuel- Faust, Janine Jansen, Alice Sara Ott and Anna ling anticipation of a new beginning. “Strauss Vinnitskaya. Yet another focus should be like this you encounter once in a decade – if mentioned: the extraordinary opportunities to you’re lucky,” as the London Times wrote about hear members of the Berliner Philharmoniker their Don Juan together. as protagonists in solo concertos. With the 2019/2020 season, the partnership We invite you to accompany the Berliner officially starts. It is a spectacular opening with Philharmoniker as they enter the Petrenko era. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, whose over- Look forward to getting to know the orchestra whelmingly joyful finale is perfect for the festive again, with fresh inspiration and new per- occasion. Just one day later, the work can be spectives, and in concerts full of energy and heard once again at an open-air concert in vibrancy. front of the Brandenburg Gate, to welcome the people of Berlin. Further highlights with Kirill Petrenko follow: the New Year’s Eve concert, www.digital-concert-hall.com featuring works by Gershwin and Bernstein, a concert together with Daniel Barenboim as the soloist, Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, Beethoven’s Fidelio at the Baden-Baden Easter Festival and in Berlin, and – for the European concert – the first appearance by the Berliner Philharmoniker in Israel for 26 years. -

Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Friday Evening, December 1, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn, Mezzo-soprano Tengku Irfan, Piano Khari Joyner, Cello LUCIANO BERIO (1925–2003) Sequenza I (1958) GIORGIO CONSOLATI, Flute Folk Songs (1965–67) Black Is the Color I Wonder as I Wander Loosin yelav Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan Love Song KADY EVANYSHYN, Mezzo-soprano Intermission BERIO Sequenza XIV (2002) KHARI JOYNER, Cello “points on the curve to find…” (1974) TENGKU IRFAN, Piano Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program faith, in spite of it all, in the lingering pres- ence of the past. This gave his work a dis- by Matthew Mendez tinctly humanistic bent, and for all his experimental impulses, Berio’s relationship LUCIANO BERIO to the musical tradition was a cord that Born October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy never would be cut. Died May 27, 2003, in Rome, Italy Sequenza I In 1968 during his tenure on the Juilliard One way Berio’s interest in -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence.