Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live-Electronic Music

live-Electronic Music GORDON MUMMA This b()oll br.gills (lnd (')uis with (1/1 flnO/wt o/Ihe s/u:CIIlflli01I$, It:clmulogira{ i,m(I1M/;OIn, find oC('(uimwf bold ;lIslJiraliml Iltll/ mm"k Ihe his lory 0/ ciec/muir 111111';(", 8u/ the oIJt:ninf!, mui dosing dlll/J/er.f IIr/! in {art t/l' l)I dilfcl'CIIt ltiJ'ton'es. 0110 Luerd ng looks UfI("/,- 1,'ulIl Ihr vll l/laga poillt of a mnn who J/(u pel'smlfl.lly tui(I/I'sscd lite 1)Inl'ch 0/ t:lcrh'Ollic tccJlIlulogy {mm II lmilll lIellr i/s beg-ilmings; he is (I fl'ndj/l(lnnlly .~{'hooletJ cOml)fJj~l' whQ Iws g/"lulll/llly (lb!Jfll'ued demenls of tlli ~ iedmoiQI!J' ;11(0 1111 a/rc(uiy-/orllleti sCI al COlli· plJSifion(l/ allillldes IInti .rki{l$. Pm' GarrlOll M umma, (m fllr. other IWfI((, dec lroll;c lerllll%gy has fllw/lys hetl! pre.telll, f'/ c objeci of 01/ fl/)sm'uillg rlln'osily (mrl inUre.fI. lu n MmSI; M 1I11111W'S Idslur)l resltllle! ",here [ . IIt:1lillg'S /(.;lIve,( nff, 1',,( lIm;lI i11g Ihe dCTleiojJlm!lIls ill dec/m1/ ;,. IIII/sir br/MI' 19j(), 1101 ~'/J IIIlIrli liS exlell siom Of $/ili em'fier lec1m%gicni p,"uedcnh b111, mOw,-, as (upcclS of lite eCQllol/lic lind soci(ll Irislm)' of the /.!I1riotl, F rom litis vh:wJ}f)il1/ Ite ('on,~i d ".r.f lHU'iQII.f kint/s of [i"t! fu! r/urmrl1lcI' wilh e/cclnmic medifl; sl/)""m;ys L'oilabomlive 1>t:rformrl1lce groU/JS (Illd speril/f "heme,f" of cIIgilli:C'-;lIg: IUltl ex/,/orcs in dt:lllil fill: in/tulmet: 14 Ihe new If'dllllJiolO' 011 pop, 10/1(, rock, nllrl jllu /Ill/SIC llJi inJlnwu:lI/s m'c modified //till Ille recording studio maltel' -

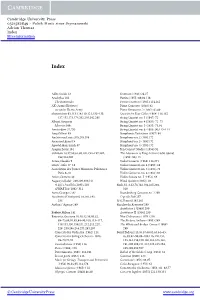

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

GB Donates to Project Extended to April Money Will Help Curb Erosion on Deadman’S Island Posals from Mid-March Until the by PAM BRANNON First of April

To advertise call (850) 932-8986 February 12, 2015 YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER 75¢ Residents City in tough spot reporting Golf course suspicious underwent activity $1.5M in BY MAT PELLEGRINO Gulf Breeze News renovations [email protected] B M P Y AT ELLEGRINO At least two people in the Tiger Gulf Breeze News [email protected] Point area came forward over the past week claiming that an individual has The City of Gulf Breeze admits been coming up to their home, knock- it sunk itself into a sand trap after ing on their door loudly and turning stating they have lost nearly $1 the knob on the door in an alleged at- million since the purchase of the tempt to get inside of the home. Tiger Point Golf Club in 2012. Erica Olson, who lives in the Crane City manager Edwin “Buz” Cove subdivision near The Club II, Eddy announced at the United said this happened to her last week Peninsula Association meeting on when it was pouring down rain with January 29 that the city had been her child inside the home. hemorrhaging money since the Another individual contacted Santa purchase. A purchase, Eddy said Rosa County deputies last Wednesday that has the city reevaluating its to report similar activity in the same plans for the golf club. general area. So far, the person has The city plans to hire a consul- not been identiied, and has not suc- tant to come in and look at what Photo by Mat Pellegrino | GBN cessfully opened any doors and en- the city can do to turn the golf tered any homes. -

“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA “Sequenza I per flauto solo ” Luciano Berio Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter Alba María Jiménez Pérez Independent Project, Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Spring Semester. Year 2020 Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring Semester. Year 2020 Author: Alba María Jiménez Pérez Title: “Sequenza I per flauto solo . Luciano Berio. Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter” Supervisor: Johan Norrback Examiner: Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT This master thesis presents a comparison between the two versions of the piece Sequenza I for solo flute, written by Luciano Berio. Finding two editions of a piece with so different approach regarding the notation is not so common and understanding the process behind their composition is really important for its interpretation. Because of that, this thesis begins with the composer’s framework as well as the evolution of the piece composition and continues with the differences between both scores. The comparison has been done from a theoretical perspective, with the scores for reference as well as from an interpretative point of view. Finally, the author explains her own decisions and conclusions regarding the interpretation of the piece, obtained from this investigation. KEY WORDS: Berio, sequenza, flute, proportional notation, traditional rhythmic notation. INDEX Backround…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….5 Introduction and methodology…………………………………………………………..………..5 1. Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1 Sequences…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.2 Evolution of the Sequenza I………………………………………………….………. -

The King's Singers the King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 3-21-1991 Concert: The King's Singers The King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The King's Singers, "Concert: The King's Singers" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5665. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5665 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 THE KING'S SINGERS David Hurley, Countertenor Alastair Hume, Countertenor Bob Chilcott, Tenor Bruce Russell, Baritone Simon Carrington, Baritone Stephen Connolly, Bass I. Folksongs of North America THE FELLER FROM FORTUNE arranged by Robert Chilcott SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW I BOUGHT ME A CAT THE GIFT TO BE SIMPLE n. Great Masters of the English Renaissance Sacred Music from Tudor England TERRA TREMUIT William Byrd 0 LORD, MAKE THY SERVANT ELIZABETH OUR QUEEN (1543-1623) SING JOYFULLY UNTO GOD OUR STRENGTH AVE MARIA Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Ill. HANDMADE PROVERBS Toro Takemitsu (b. 1930) CRIES OF LONDON Luciano Berio (b. 1925) INTERMISSION IV. SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN OPERA Paul Drayton (b. 1944) v. Arrangements in Close Harmony Selections from the Lighter Side of the Repertoire Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, March 21, 1991 8:15 p.m. The King's Singers are represented by IMG Artists, New York. -

AMRC Journal Volume 21

American Music Research Center Jo urnal Volume 21 • 2012 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder The American Music Research Center Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Dominic Ray, O. P. (1913 –1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music Eric Hansen, Editorial Assistant Editorial Board C. F. Alan Cass Portia Maultsby Susan Cook Tom C. Owens Robert Fink Katherine Preston William Kearns Laurie Sampsel Karl Kroeger Ann Sears Paul Laird Jessica Sternfeld Victoria Lindsay Levine Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Kip Lornell Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25 per issue ($28 outside the U.S. and Canada) Please address all inquiries to Eric Hansen, AMRC, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. Email: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISBN 1058-3572 © 2012 by Board of Regents of the University of Colorado Information for Authors The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing arti - cles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and proposals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (exclud - ing notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, Uni ver - sity of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. Each separate article should be submitted in two double-spaced, single-sided hard copies. -

The Full Concert Program and Notes (Pdf)

Program Sequenza I (1958) for fl ute Diane Grubbe, fl ute Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe Kyle Bruckmann, oboe O King (1968) for voice and fi ve players Hadley McCarroll, soprano Diane Grubbe, fl ute Matt Ingalls, clarinet Mark Chung, violin Erik Ulman, violin Christopher Jones, piano David Bithell, conductor Sequenza V (1965) for trombone Omaggio Toyoji Tomita, trombone Interval a Berio Laborintus III (1954-2004) for voices, instruments, and electronics music by Luciano Berio, David Bithell, Christopher Burns, Dntel, Matt Ingalls, Gustav Mahler, Photek, Franz Schubert, and the sfSound Group texts by Samuel Beckett, Luciano Berio, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Paul Griffi ths, Ezra Pound, and Eduardo Sanguinetti David Bithell, trumpet; Kyle Bruckmann, oboe; Christopher Burns, electronics / reciter; Mark Chung, violin; Florian Conzetti, percussion; Diane Grubbe, fl ute; Karen Hall, soprano; Matt Ingalls, clarinets; John Ingle, soprano saxophone; Christopher Jones, piano; Saturday, June 5, 2004, 8:30 pm Hadley McCarroll, soprano; Toyoji Tomita, trombone; Erik Ulman, violin Community Music Center Please turn off cell phones, pagers, and other 544 Capp Street, San Francisco noisemaking devices prior to the performance. Sequenza I for solo flute (1958) Sequenza V for solo trombone (1965) Sequenza I has as its starting point a sequence of harmonic fields that Sequenza V, for trombone, can be understood as a study in the superposition generate, in the most strongly characterized ways, other musical functions. of musical gestures and actions: the performer combines and mutually Within the work an essentially harmonic discourse, in constant evolution, is transforms the sound of his voice and the sound proper to his instrument; in developed melodically. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

Hiroya Miura

CURRICULUM VITAE HIROYA MIURA Department of Music 30 Preble Street, #253 Bates College Portland, ME 04101 75 Russell Street Mobile Phone: (917) 488-4085 Lewiston, ME 04240 [email protected] http://www.myspace.com/hiroyamusic EDUCATION 2007 D.M.A. (Doctor of Musical Arts) in Composition Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University, New York, NY Advisor: Professor Fred Lerdahl Dissertation: Cut for Satsuma Biwa and Chamber Orchestra 2001 M.A. in Composition Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University, New York, NY 1998 B.Mus. in Composition (Honors with Distinction) Faculty of Music McGill University, Montréal, QC 1995 D.E.C. (Diplôme d’études collégiales) in Pure and Applied Sciences Marianopolis College, Montréal, QC TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2005-Present Bates College Assistant Professor of Music Conductor of College Orchestra Courses Taught: Music Theory I, Music Theory III and IV, Music Composition, Music and Cinema, Introduction to Listening, Orchestration, Undergraduate Theses in Composition 1999-2005 Columbia University Teaching Fellow (2002-2005), Assistant Conductor of University Orchestra (1999-2002) Courses Taught: Introductory Ear Training (Instructor), Chromatic Harmony and Advanced Composition (Teaching Assistant) Hiroya Miura Curriculum Vitae CONDUCTING / PERFORMANCE EXPERIENCE Calling ---Opera of Forgiveness---* Principal Conductor Electronic Quartet with Jorge Sad, Santiago Diez, and Matias Giuliani at CCMOCA* No-Input Mixer performer Bates College Orchestra Music Director/ Principal Conductor Columbia