Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthias Theodor Vogt, Ulf Großmann (Text) Unter Mitwirkung Von Andreas Herrmann (Materialien)

i Matthias Theodor Vogt, Ulf Großmann (Text) unter Mitwirkung von Andreas Herrmann (Materialien) Szenarien-Entwicklung in der Haushaltsplanung der Stadt Pforzheim für das Südwestdeutsche Kammerorchester Pforzheim (SWDKO) Edition kulturelle Infrastruktur ii Edition kulturelle Infrastruktur Inhaltsverzeichnis 0. VERZEICHNIS der im Anhang abgedruckten Dokumente zum Südwestdeutschen Kammerorchester Pforzheim......................................................................... iii 1. ANALYSE .....................................................................................................1 1.1. Haushaltslage........................................................................................1 1.2. Namensgebung......................................................................................3 1.3. Künstlerische Stellung ............................................................................7 1.4. Wirtschaftlichkeit ...................................................................................9 1.5. Das Format Kammerorchester ............................................................... 14 1.6. Ausland .............................................................................................. 15 2. U LTRA VIRES............................................................................................. 17 2.1 Rechtsk onformität................................................................................ 17 2.2 Rechtslage ......................................................................................... -

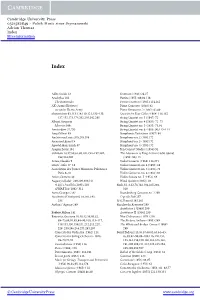

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

What Is Cultural Policy?

Matthias Theodor Vogt Prof. Dr. phil. Dr. habil. Klingewalde 40 D-02828 Görlitz Tel. +49/3581/42094.21 Fax 28 Mail: [email protected] Görlitz, March 2010 What is Cultural Policy? 1. A budget orientated approach·················································································· 2 2. Federation level, Länder level, Community level, Multicommunity level, Churches ·········· 5 3. The international union of states off the track? ·························································· 7 4. Radio and TV stations as ‘media and factors’ of culture ··············································· 9 4.1. Supply orientation versus demand orientation?·················································10 4.2. Reports medium versus a proper medium of art ···············································12 4.3. TV as a manifestation of mentality ··································································13 5. The shaping of frameworks for the arts through the elaborating of legal norms············13 6. Culture as an economic phenomenon·······································································14 7. Civil society··········································································································19 8. The humanities ·····································································································21 8.1. What are the humanities? ··············································································22 8.2. The humanities in the German system of higher education·································25 -

The Shaping of Time in Kaija Saariaho's Emilie

THE SHAPING OF TIME IN KAIJA SAARIAHO’S ÉMILIE: A PERFORMER’S PERSPECTIVE Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS May 2020 Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Brent E. Archer Graduate Faculty Representative Elaine J. Colprit Nora Engebretsen-Broman © 2020 Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor This document examines the ways in which Kaija Saariaho uses texture and timbre to shape time in her 2008 opera, Émilie. Building on ideas about musical time as described by Jonathan Kramer in his book The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies (1988), such as moment time, linear time, and multiply-directed time, I identify and explain how Saariaho creates linearity and non-linearity in Émilie and address issues about timbral tension/release that are used both structurally and ornamentally. I present a conceptual framework reflecting on my performance choices that can be applied in a general approach to non-tonal music performance. This paper intends to be an aid for performers, in particular conductors, when approaching contemporary compositions where composers use the polarity between tension and release to create the perception of goal-oriented flow in the music. iv To Adeli Sarasola and Denise Zephier, with gratitude. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the many individuals who supported me during my years at BGSU. First, thanks to Dr. Emily Freeman Brown for offering me so many invaluable opportunities to grow musically and for her detailed corrections of this dissertation. -

Melody Baggech, Fruit Bag, Babel, Credo for Plastical Score, Etc

Melody Baggech 2100 Fullview Drive, Ada, Oklahoma 74820 | (580) 235-5822 | [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE Professor of Voice – East Central University, 2018-present Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Associate Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2010-2018 Private Studio Voice, Music Theatre Voice, Opera/Musical Theatre Workshop, Diction I and II, Vocal Pedagogy, Music Appreciation, Beginning Italian. Actively recruit and perform. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Assistant Professor of Voice - East Central University, 2001-2010 Private Studio Voice, Opera Theatre, Diction, Vocal Literature, Beginning Italian, Gospel Singers. Actively recruit and perform. Expanded existing opera program to include full-length performances and collaboration with ECU’s Theatre Department, local theatre companies and professional regional opera company. Assist with production of departmental vocal events. Faculty, StartTalk Russian Language Camp, ECU 2012. Subjects taught: Russian folk song, Russian opera, Russian art song/poetry Adjunct Instructor of Voice, Panhandle State University, 1991-1993 Taught private studio voice, accompanied student juries. Performed in faculty recital series. Instructor of Voice, University of Oklahoma, March 20-April 27, 2000 Taught private studio voice to majors and non-majors. Private Studio Voice, Suburban Washington D.C., 2000-2001 Graduate Teaching Assistant, West Texas A&M University, 1988-1990 Voice Instructor, Moore High School, Moore, Oklahoma, 1998-1999 Voice Instructor, Travis Middle School, Amarillo, Texas, 1990-1991 EDUCATION DMA Vocal Performance, University of Oklahoma, 1998 Dissertation – An English Translation of Olivier Messiaen’s Traité de Rythme, de Couleur, et d’Ornithologie vol. -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Intolleranza 1960

FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA Intertestualità relativa al libretto: Angelo Maria Ripellino, Vivere è stare svegli in Angelo Maria Ripellino, Non un giorno ma adesso, in Poesie prime e ultime, Torino, Aragno, 2006 Lirica 2011 Henri Alleg, La tortura, con uno scritto di J.-P. Sartre, Torino, Einaudi 1958 Roberto Fertonani (a cura di), A coloro che verranno in Per conoscere Brecht, antologia delle opere, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milano 1970 Sentieri esplorativi & Risorse di studio Paul Éluard, Liberté, dal sito internet: http://eddyburg.it/article/articleview/3309/0/25/ Franco Calamandrei (cura di), Julius Fucik, Scritto sotto la forca, Universale Economica, Milano 1951 per studenti di scuola secondaria di II grado, La cancrena, Einaudi, Torino 1959 università, conservatorio, educazione permanente Vladimir Maiakovski, La nostra marcia dal sito internet: http://italpag.altervista.org/6_letteratura/letteratura17.htm Intertestualità relativa ai contesti storici e sociali richiamati dalla composizione di Nono: Documenti audiovisivi: Intolerance, un film di David Wark Griffith con Lilian Gish, Mae Marsh, Robert Harron, Tully Marshall e Howard Gaye. Wark Producing Corporation - USA 1916, Ermitage 2005 Henri Alleg, giornalista francese e direttore di Alger républicain, quotidiano algerino di opposizione, dibatte sul tema della tortura in un’intervista, condotta da Amy Goodman per conto dell’emittente televisiva statunitense Democracy Now (testo in lingua inglese e estratto audiovisivo in http://www.democracynow.org/blog/2010/12/29/watch_amy_goodman_on_cnns_john_king_usa) La battaglia di Algeri, un film di Gillo Pontecorvo con Yacef Saadi, Jean Martin, Michèle Fawzia El Kader, Ugo Paletti e Tommaso Neri. Igor Film e Casbah Film - Italia 1966, Surf Video 2005 Borinage, un documentario di Joris Ivens e Henri Stork - Belgio 1934 (sulla condizione degli emigranti italiani in Belgio) Marcinelle, un film di Andrea e Antonio Frazzi con Claudio Amendola, Maria Grazia Cucinotta, Antonio Manzini e Lorenza Indovina. -

Thesis Submission

Rebuilding a Culture: Studies in Italian Music after Fascism, 1943-1953 Peter Roderick PhD Music Department of Music, University of York March 2010 Abstract The devastation enacted on the Italian nation by Mussolini’s ventennio and the Second World War had cultural as well as political effects. Combined with the fading careers of the leading generazione dell’ottanta composers (Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Ildebrando Pizzetti), it led to a historical moment of perceived crisis and artistic vulnerability within Italian contemporary music. Yet by 1953, dodecaphony had swept the artistic establishment, musical theatre was beginning a renaissance, Italian composers featured prominently at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse , Milan was a pioneering frontier for electronic composition, and contemporary music journals and concerts had become major cultural loci. What happened to effect these monumental stylistic and historical transitions? In addressing this question, this thesis provides a series of studies on music and the politics of musical culture in this ten-year period. It charts Italy’s musical journey from the cultural destruction of the post-war period to its role in the early fifties within the meteoric international rise of the avant-garde artist as institutionally and governmentally-endorsed superman. Integrating stylistic and aesthetic analysis within a historicist framework, its chapters deal with topics such as the collective memory of fascism, internationalism, anti- fascist reaction, the appropriation of serialist aesthetics, the nature of Italian modernism in the ‘aftermath’, the Italian realist/formalist debates, the contradictory politics of musical ‘commitment’, and the growth of a ‘new-music’ culture. In demonstrating how the conflict of the Second World War and its diverse aftermath precipitated a pluralistic and increasingly avant-garde musical society in Italy, this study offers new insights into the transition between pre- and post-war modernist aesthetics and brings musicological focus onto an important but little-studied era. -

The Full Concert Program and Notes (Pdf)

Program Sequenza I (1958) for fl ute Diane Grubbe, fl ute Sequenza VII (1969) for oboe Kyle Bruckmann, oboe O King (1968) for voice and fi ve players Hadley McCarroll, soprano Diane Grubbe, fl ute Matt Ingalls, clarinet Mark Chung, violin Erik Ulman, violin Christopher Jones, piano David Bithell, conductor Sequenza V (1965) for trombone Omaggio Toyoji Tomita, trombone Interval a Berio Laborintus III (1954-2004) for voices, instruments, and electronics music by Luciano Berio, David Bithell, Christopher Burns, Dntel, Matt Ingalls, Gustav Mahler, Photek, Franz Schubert, and the sfSound Group texts by Samuel Beckett, Luciano Berio, Dante, T. S. Eliot, Paul Griffi ths, Ezra Pound, and Eduardo Sanguinetti David Bithell, trumpet; Kyle Bruckmann, oboe; Christopher Burns, electronics / reciter; Mark Chung, violin; Florian Conzetti, percussion; Diane Grubbe, fl ute; Karen Hall, soprano; Matt Ingalls, clarinets; John Ingle, soprano saxophone; Christopher Jones, piano; Saturday, June 5, 2004, 8:30 pm Hadley McCarroll, soprano; Toyoji Tomita, trombone; Erik Ulman, violin Community Music Center Please turn off cell phones, pagers, and other 544 Capp Street, San Francisco noisemaking devices prior to the performance. Sequenza I for solo flute (1958) Sequenza V for solo trombone (1965) Sequenza I has as its starting point a sequence of harmonic fields that Sequenza V, for trombone, can be understood as a study in the superposition generate, in the most strongly characterized ways, other musical functions. of musical gestures and actions: the performer combines and mutually Within the work an essentially harmonic discourse, in constant evolution, is transforms the sound of his voice and the sound proper to his instrument; in developed melodically. -

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(S): David Osmond-Smith Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Berio and the Art of Commentary Author(s): David Osmond-Smith Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1592, (Oct., 1975), pp. 871-872 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/959202 Accessed: 21/05/2008 10:04 By purchasing content from the publisher through the Service you agree to abide by the Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. These Terms and Conditions of Use provide, in part, that this Service is intended to enable your noncommercial use of the content. For other uses, please contact the publisher of the journal. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mtpl. Each copy of any part of the content transmitted through this Service must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. For more information regarding this Service, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org As for Alice herself, when she marriedin February taking tea with Adele.12 Brahms seems to have 1896, Brahms was invited to be best man, an been pleased with the results. 'Have I actually sent invitation he declined only because he could not you the double portrait of Strauss and me?', he face the prospect of having to wear top hat and asked Simrock(30 October 1894), 'or does the com- white gloves. Alice's husband was the painter poser of Jabuka no longer interestyou?' But here, Franzvon Bayros,who in 1894,for the goldenjubilee too, matters of dress caused him concern. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXTENDED FROM WHAT?: TRACING THE CONSTRUCTION, FLEXIBLE MEANING, AND CULTURAL DISCOURSES OF “EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES” A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Charissa Noble March 2019 The Dissertation of Charissa Noble is approved: Professor Leta Miller, chair Professor Amy C. Beal Professor Larry Polansky Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Charissa Noble 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgements and Dedications viii Introduction to Extended Vocal Techniques: Concepts and Practices 1 Chapter One: Reading the Trace-History of “Extended Vocal Techniques” Introduction 13 The State of EVT 16 Before EVT: A Brief Note 18 History of a Construct: In Search of EVT 20 Ted Szántó (1977): EVT in the Experimental Tradition 21 István Anhalt’s Alternative Voices (1984): Collecting and Codifying EVT 28evt in Vocal Taxonomies: EVT Diversification 32 EVT in Journalism: From the Musical Fringe to the Mainstream 42 EVT and the Classical Music Framework 51 Chapter Two: Vocal Virtuosity and Score-Based EVT Composition: Cathy Berberian, Bethany Beardslee, and EVT in the Conservatory-Oriented Prestige Economy Introduction: EVT and the “Voice-as-Instrument” Concept 53 Formalism, Voice-as-Instrument, and Prestige: Understanding EVT in Avant- Garde Music 58 Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio 62 Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt 81 Conclusion: The Plight of EVT Singers in the Avant-Garde -

Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn

Friday Evening, December 1, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Giorgio Consolati, Flute Kady Evanyshyn, Mezzo-soprano Tengku Irfan, Piano Khari Joyner, Cello LUCIANO BERIO (1925–2003) Sequenza I (1958) GIORGIO CONSOLATI, Flute Folk Songs (1965–67) Black Is the Color I Wonder as I Wander Loosin yelav Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan Love Song KADY EVANYSHYN, Mezzo-soprano Intermission BERIO Sequenza XIV (2002) KHARI JOYNER, Cello “points on the curve to find…” (1974) TENGKU IRFAN, Piano Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 20 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program faith, in spite of it all, in the lingering pres- ence of the past. This gave his work a dis- by Matthew Mendez tinctly humanistic bent, and for all his experimental impulses, Berio’s relationship LUCIANO BERIO to the musical tradition was a cord that Born October 24, 1925, in Oneglia, Italy never would be cut. Died May 27, 2003, in Rome, Italy Sequenza I In 1968 during his tenure on the Juilliard One way Berio’s interest in