Form and Virtuosity in Luciano Berio's Sequenza I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

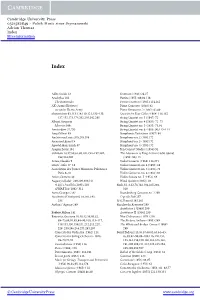

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

School of Music Undergraduate Journal

39 20th Century Discussions on Instrumentation and Timbre in Regards to Pierre Boulez and Le marteau sans maître By: Elsa Marshall As elements of music, including tonality, rhythm, and form, became more and more unfamiliar in modern compositions of the 20th century, the instrumentation of a piece sometimes provided the only link to the familiarity of Western art music. The use of unconventional timbres in other pieces further weakened relations to what was conventionally understood to be music and lead to intellectual debates on what is sound and what is music. The role of electronic instruments and machines in composition, as well as the inclusion of non-Western instruments beyond the role of sound effects, were new considerations for composers of the time. For some, the inclusion of these new sounds was necessary to the development of new music. In this paper I will first discuss composers John Cage, Edgard Varèse, and Pierre Boulez's ideas about instruments and timbres. I will then examine Boulez's ideas more specifically and how these relate to the aforementioned ideas. Finally, I will study various analyses of his instrumentation in Le marteau sans maître (1952-55) in relation to these modern debates. Discussions of Technology and Sound in Compositions and Writings of Boulez, Varèse, and Cage A large part of the discussions about defining music in the writings and interviews of Cage, Varèse, and Boulez consists of the analysis of timbres used in musical composition. More specifically, there are debates over the role of timbre in composition and the distinction or lack thereof between an object that produces sound and a musical instrument. -

HINDEMITH VAN DER ROOST Clarinet Concertos Eddy Vanoosthuyse, Clarinet Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra Sergio Rosales, Conductor

HINDEMITH VAN DER ROOST Clarinet Concertos Eddy Vanoosthuyse, Clarinet Central Aichi Symphony Orchestra Sergio Rosales, Conductor 1 Paul Hindemith (1895−1963): Clarinet Concerto Born in Frankfurt in 1895, the son of a house-painter, Paul Hindemith studied the violin privately with teachers from the Hoch Conservatory before being admitted to that institution with a free place at the age of thirteen. By 1915 he was playing second violin in his teacher Adolf Rebner’s quartet and had a place in the opera orchestra, of which he became leader in the same year. His father was killed in the war and Hindemith himself spent some time from 1917 as a member of a regimental band, returning after the war to the Rebner Quartet and the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. At the same time he was making his name as a composer of particular originality, striving to bring about a revolution in concert-going with his concept of Gebrauchsmusik (functional or utility music), and devoting much of his energy to the promotion of new music, in particular at the Donaueschingen Festival. Having changed from violin to viola, he formed the Amar-Hindemith Quartet in 1921, an ensemble that won considerable distinction for its performances of new music. In 1927 Hindemith was appointed professor of composition at the Berlin Musikhochschule, two years later disbanding the quartet – to which he could no longer give time – and instead performing in a string trio with Josef Wolfsthal, (replaced on his death by Szymon Goldberg) and the cellist Emanuel Feuermann. He was also enjoying a career as a viola soloist. -

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

A Conductor's Study of George Rochberg's Three Psalm Settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2002 A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings David Lawrence Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, David, "A conductor's study of George Rochberg's three psalm settings" (2002). LSU Major Papers. 51. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/51 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONDUCTOR’S STUDY OF GEORGE ROCHBERG’S THREE PSALM SETTINGS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in School of Music By David Alan Lawrence B.M.E., Abilene Christian University, 1987 M.M., University of Washington, 1994 August 2002 ©Copyright 2002 David Alan Lawrence All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................vi LIST -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Fylkingen's Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974

Fylkingen’s Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974 Teddy Hultberg Abstract In the 1960s the concept and the genre of “text-sound composition” were born in Sweden. Being an offspring of sound poetry in various forms and of the new electro- acoustic music of the post-war years, it took shape as an intermedia art form par excel- lence. This essay traces the emergence of text-sound in a Swedish context and especially its appearance at the internationally renowned text-sound festivals held at Fylkingen in Stockholm during the years 1968–1974. By the time the term was invented in the 1960, text-sound composition, as an aesthetic practice, was already an international phenomenon. The Swedish version of this intermedia genre was given an international plat- form through the famous text-sound festivals that were organised by Fylkingen in Stockholm between 1968 and 1974. Founded as a chamber music society in 1933, Fylkingen had at this time developed into an organisa- tion that promoted all the new events in music, dance and theatre. And in this context sound poetry and text-sound composition appeared to be typi- cal art forms of the time – art forms that would explore the interstices between word and sound, poetry and music, and which would further the investigation of the electro-acoustic landscape staked out in avant-garde music from the post-war period by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luciano Berio. In short, the history of text-sound composition can be seen as the history of how technology during the early 1960s changed the poetic expression when it opened the literary field to a new kind of sound poetry. -

“Sequenza I Per Flauto Solo” Luciano Berio Differences Between

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA “Sequenza I per flauto solo ” Luciano Berio Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter Alba María Jiménez Pérez Independent Project, Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Spring Semester. Year 2020 Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music with Specialisation in Symphonic Orchestra Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring Semester. Year 2020 Author: Alba María Jiménez Pérez Title: “Sequenza I per flauto solo . Luciano Berio. Differences between the proportional notation edition and the traditional rhythmic edition and its implications for the interpreter” Supervisor: Johan Norrback Examiner: Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT This master thesis presents a comparison between the two versions of the piece Sequenza I for solo flute, written by Luciano Berio. Finding two editions of a piece with so different approach regarding the notation is not so common and understanding the process behind their composition is really important for its interpretation. Because of that, this thesis begins with the composer’s framework as well as the evolution of the piece composition and continues with the differences between both scores. The comparison has been done from a theoretical perspective, with the scores for reference as well as from an interpretative point of view. Finally, the author explains her own decisions and conclusions regarding the interpretation of the piece, obtained from this investigation. KEY WORDS: Berio, sequenza, flute, proportional notation, traditional rhythmic notation. INDEX Backround…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….5 Introduction and methodology…………………………………………………………..………..5 1. Theoretical framework……………………………………………………………………….6 1.1 Sequences…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.2 Evolution of the Sequenza I………………………………………………….………. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

The King's Singers the King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 3-21-1991 Concert: The King's Singers The King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The King's Singers, "Concert: The King's Singers" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5665. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5665 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 THE KING'S SINGERS David Hurley, Countertenor Alastair Hume, Countertenor Bob Chilcott, Tenor Bruce Russell, Baritone Simon Carrington, Baritone Stephen Connolly, Bass I. Folksongs of North America THE FELLER FROM FORTUNE arranged by Robert Chilcott SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW I BOUGHT ME A CAT THE GIFT TO BE SIMPLE n. Great Masters of the English Renaissance Sacred Music from Tudor England TERRA TREMUIT William Byrd 0 LORD, MAKE THY SERVANT ELIZABETH OUR QUEEN (1543-1623) SING JOYFULLY UNTO GOD OUR STRENGTH AVE MARIA Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Ill. HANDMADE PROVERBS Toro Takemitsu (b. 1930) CRIES OF LONDON Luciano Berio (b. 1925) INTERMISSION IV. SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN OPERA Paul Drayton (b. 1944) v. Arrangements in Close Harmony Selections from the Lighter Side of the Repertoire Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, March 21, 1991 8:15 p.m. The King's Singers are represented by IMG Artists, New York. -

Survey of Music History I

MUHL M106 Introduction to Music Literature 2 credits Spring semester 2019 Ravi Shankar and Philip Glass working on Passages, 1990 (image from Maria Popova, “Remembering the Godfather of World Music: Ravi Shankar + Philip Glass, 1990,” Brain Pickings (13 December 2013), https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/12/13/pa ssages-ravi-shankar-philip-glass-1990/ , accessed 1 January 2020) Classes TR 8:30-9:20, CM 204g WF 10:30-11:20, CM 135 Bulletin description This course is an introduction to fundamental musical concepts and terminology as applied to listening skills. Students will study a selected body of standard genres and styles used in western art music from c. 800 to the present. This semester I am experimenting: rather than the “snapshots” focused on single pieces we have used in this course in recent years, we will consider specific decades (“snapshots”) in the “long twentieth century” (for me starting in 1889, the year Claude Debussy encountered gamelan music at the Paris World Exhibition), bringing together musics from across the traditional boundaries of western art music (aka “classical” music), jazz, popular, and world musics. We will, as usual, begin with a more general unit on the elements of music. A major focus throughout the course will be on developing skills in active listening and writing/talking about music. Prerequisites Co-requisite: MUTH-M103. This means you must currently be taking (or have taken) Theory II. Please let me know if you have questions on this front or are unsure if this course is appropriate for you. This course is not available for Loyola Core credit.