Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Regional Music Scholars Conference Abstracts Friday, March 27 Paper Session 1 1:00-3:05

2015 REGIONAL MUSIC SCHOLARS CONFERENCE A Joint Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory (RMSMT), Society for Ethnomusicology, Southwest Chapter (SEMSW), and Rocky Mountain Chapter of the American Musicological Society (AMS-RMC) School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, Colorado State University March 27 and 28, 2015 ABSTRACTS FRIDAY, MARCH 27 PAPER SESSION 1 1:00-3:05— NEW APPROACHES TO FORM (RMSMT) Peter M. Mueller (University of Arizona) Connecting the Blocks: Formal Continuity in Stravinsky’s Sérénade en La Phrase structure and cadences did not expire with the suppression of common practice tonality. Joseph Straus points out the increased importance of thematic contrast to delineate sections of the sonata form in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Igor Stravinsky exploited other musical elements (texture, range, counterpoint, dynamics, etc.) to delineate sections in his neoclassical works. While theorists have introduced large-scale formal approaches to Stravinsky’s works (block juxtaposition, stratification, etc.), this paper presents an examination of smaller units to determine how they combine to form coherence within and between blocks. The four movements of the Sérénade present unique variations of phrase construction and continuity between sections. The absence of clear tonic/dominant relationships calls for alternative formal approaches to this piece. Techniques of encirclement, enharmonic ties, and rebarring reveal methods of closure. Staggering of phrases, cadences, and contrapuntal lines aid coherence to formal segments. By reversing the order of phrases in outer sections, Stravinsky provides symmetrical “bookends” to frame an entire movement. Many of these techniques help to identify traditional formal units, such as phrases, periods, and small ternary forms. -

Musical Notations 3

F.A.P. May/June 1971 Musical Notations on Stamps: Part 3 By J. Posell Since my last article on this subject which appeared in FAP Journals (Vol. 14, 4 and 5), a number of stamps have been issued with musical notation which have aroused considerable interest and curiosity. Rather than waiting the five year period which I promised our readers, I have been prevailed upon to compile a listing of these issues now. Some of the information contained here has already been sent to different collectors who made inquiries of me; some of it has already appeared in print. However, it seems appropriate to include it all under one roof again and so I beg the indulgence of my friends who may find some of this reading repetitious. AJMAN Scott ??? Michel 427 A This issue was described in detail by this writer in the Western Stamp Collector for 16 May 1970. The issue consists of four stamps and a souvenir sheet all issued both perforated and imperforate. The imperforate stamps include the musical quotation both at top and bottom plus a picture of a violin in the border at right. The notation is strangely incorrect on all issues. The following information is extracted from the above article. The music on the Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) stamp is the opening chorale from the St. Matthew Passion (Ah dearest Jesu), Bach's most famous oratorio. This is originally written in the key of B minor but on the stamp it has been transposed down to the key of G minor. -

Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017

AAP: Music American nostalgia: Samuel Barber (1910-81), Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017 Aaron Copland • Parents immigrated to the US and opened a furniture store in Brooklyn • Youngest of five children • Began studying piano at age 13 • Studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) • The school of music at CUNY Queens College is named after him: Aaron Copland School of Music Career: • Composed – musical style incorporates Latin American (Brazilian, Cuban, Mexican), Jewish, Anglo-American, and African-American (jazz) sources • Conducted (1958-78) • Wrote essays about music • Visiting teaching positions (New School for Social Research, Henry Street Settlement, Harvard University) • Public lectures (Harvard’s Norton Professor of Poetics, 1951-52) Copland organized concerts that promoted the music of his peers: Marc Blitzstein (1905-64) Roy Harris (1898-1979) Paul Bowles (1910-99) Charles Ives (1874-1954) Henry Brant (1913-2008) Walter Piston (1894-1976) Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) Carl Ruggles (1876-1971) Israel Citkowitz (1909-74) Roger Sessions (1896-1985) Vivian Fine (1913-2000) Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) Copland was a mentor to younger composers: Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) Irving Fine (1914-62) David del Tredici (b. 1937) Lukas Foss (1922-2009) David Diamond (1915-2005) Barbara Kolb (b. 1939) Jacob Druckman (1928-96) William Schuman (1910-92) Elliott Carter (1908-2012) AAP: Music Selected works Orchestra Ballets (also published as orchestral suites) Music for the Theatre (1925) Billy the Kid -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

Luciano Berio's Sequenza V Analyzed Along the Lines of Four Analytical

Peer-Reviewed Paper JMM: The Journal of Music and Meaning, vol.9, Winter 2010 Luciano Berio’s Sequenza V analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer Niels Chr. Hansen, Royal Academy of Music Aarhus, Denmark and Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK Abstract In this paper, Luciano Berio’s ‘Sequenza V’ for solo trombone is analyzed along the lines of four analytical dimensions proposed by the composer himself in an interview from 1980. It is argued that the piece in general can be interpreted as an exploration of the ‘morphological’ dimension involving transformation of the traditional image of the trombone as an instrument as well as of the performance context. The first kind of transformation is revealed by simultaneous singing and playing, continuous sounds and considerable use of polyphony, indiscrete pitches, plunger, flutter-tongue technique, and unidiomatic register, whereas the latter manifests itself in extra-musical elements of theatricality, especially with reference to clown acting. Such elements are evident from performance notes and notational practice, and they originate from biographical facts related to the compositional process and to Berio’s sources of inspiration. Key topics such as polyphony, amalgamation of voice and instrument, virtuosity, theatricality, and humor – of which some have been recognized as common to the Sequenza series in general – are explained in the context of the analytical model. As a final point, a revised version of the four-dimensional model is presented in which tension-inducing characteristics in the ‘pitch’, ‘temporal’ and ‘dynamic’ dimensions are grouped into ‘local’ and ‘global’ components to avoid tension conflicts within dimensions. -

El Lenguaje Musical De Luciano Berio Por Juan María Solare

El lenguaje musical de Luciano Berio por Juan María Solare ( [email protected] ) El compositor italiano Luciano Berio (nacido en Oneglia el 24 de octubre de 1925, muerto en Roma el 27 de mayo del 2003) es uno de los más imaginativos exponentes de su generación. Durante los años '50 y '60 fue uno de los máximos representantes de la vanguardia oficial europea, junto a su compatriota Luigi Nono, al alemán Karlheinz Stockhausen y al francés Pierre Boulez. Si lograron sobresalir es porque por encima de su necesidad de novedad siempre estuvo la fuerza expresiva. Gran parte de las obras de Berio ha surgido de una concepción estructuralista de la música, entendida como un lenguaje de gestos sonoros; es decir, de gestos cuyo material es el sonido. (Con "estructuralismo" me refiero aquí a una actitud intelectual que desconfía de aquellos resultados artísticos que no estén respaldados por una estructura justificable en términos de algún sistema.) Los intereses artísticos de Berio se concentran en seis campos de atención: diversas lingüísticas, los medios electroacústicos, la voz humana, el virtuosismo solista, cierta crítica social y la adaptación de obras ajenas. Debido a su interés en la lingüística, Berio ha examinado musicalmente diversos tipos de lenguaje: 1) Lenguajes verbales (como el italiano, el español o el inglés), en varias de sus numerosas obras vocales; 2) Lenguajes de la comunicación no verbal, en obras para solistas (ya sean cantantes, instrumentistas, actores o mimos); 3) Lenguajes musicales históricos, como -por ejemplo- el género tradicional del Concierto, típico del siglo XIX; 4) Lenguajes de las convenciones y rituales del teatro; 5) Lenguajes de sus propias obras anteriores: la "Sequenza VI" para viola sola (por ejemplo) fue tomada por Berio tal cual, le agregó un pequeño grupo de cámara, y así surgió "Chemins II". -

CHAN 3094 BOOK.Qxd 11/4/07 3:13 Pm Page 2

CHAN 3094 Book Cover.qxd 11/4/07 3:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 3094(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH PETER MOORES FOUNDATION CHAN 3094 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:13 pm Page 2 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Wozzeck Opera in three acts (fifteen scenes), Op. 7 Libretto by Alban Berg after Georg Büchner’s play Woyzeck Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht English translation by Richard Stokes Wozzeck, a soldier.......................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Drum Major .................................................................................................Alan Woodrow tenor Andres, a soldier...............................................................................................Peter Bronder tenor Captain ................................................................................................................Stuart Kale tenor Doctor .................................................................................................................Clive Bayley bass First Apprentice................................................................................Leslie John Flanagan baritone Second Apprentice..............................................................................................Iain Paterson bass The Idiot..................................................................................................John Graham-Hall tenor Marie ..........................................................................................Dame Josephine Barstow soprano Margret ..................................................................................................Jean -

Defining Instrumental Collage Music in Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi

TEMPERED CONFETTI: DEFINING INSTRUMENTAL COLLAGE MUSIC IN TEMPERED CONFETTI AND VENNI, VIDDI, – Andrew Campbell Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2016 APPROVED: Panayiotis Kokoras, Major Professor Jon Nelson, Committee Member Joseph Klein, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Music Composition John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Campbell, Andrew S. Tempered Confetti: Defining Instrumental Collage Music in Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi, –. Master of Arts (Composition), August 2016, 83 pp., 4 figures, 9 examples, bibliography, 40 titles. This thesis explores collage music's formal elements in an attempt to better understand its various themes and apply them in a workable format. I explore the work of John Zorn; how time is perceived in acoustic collage music and the concept of "super tempo"; musical quotation and appropriation in acoustic collage music; the definition of acoustic collage music in relation to other acoustic collage works; and musical montages addressing the works of Charles Ives, Lucciano Berio, George Rochberg, and DJ Orange. The last part of this paper discusses the compositional process used in the works Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi, – and how all issues of composing acoustic collage music are addressed therein. Copyright 2016 by Andrew Campbell ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................v -

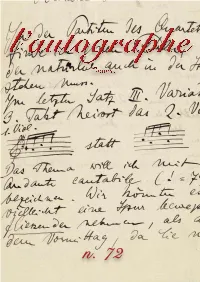

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. 1. Richard Adler (New York City, 1921 - Southampton, 2012) Autograph dedication signed on the frontispiece of the musical score of the popular song “Whatever Lola Wants” from the musical comedy “Damn Yankees” by the American composer and producer of several Broadway shows and his partner Jerry Ross. 5 pp. In fine condition. Countersigned with signature and dated “6/2/55” by the accordionist Muriel Borelli. $ 125/Fr. 115/€ 110 2. Franz Allers (Carlsbad, 1905 - Paradise, 1995) Photo portrait with autograph dedication and musical quotation signed, dated June 1961 of the Czech born American conductor of ballet, opera and Broadway musicals. (8 x 10 inch.). In fine condition. -

Seattle Symphony Media Releases Berio's Sinfonia

IMMEDIATE RELEASE JUNE 27, 2018 Shiva Shafii Public Relations Manager 206.215.4758 | [email protected] Rosalie Contreras Vice President of Communications 206.215.4782 | [email protected] “A crashing ocean of sound as Roomful of Teeth joins Seattle Symphony" – The Seattle Times SEATTLE SYMPHONY MEDIA RELEASES BERIO’S SINFONIA FEATURING GRAMMY-WINNING ENSEMBLE ROOMFUL OF TEETH ON JULY 20 ALBUM INCLUDES VIBRANT PERFORMANCES OF BOULEZ’S NOTATIONS I–IV AND RAVEL’S LA VALSE Ludovic Morlot leads the Seattle Symphony and Roomful of Teeth in a performance of Berio’s Sinfonia. Photo by Brandon Patoc. AVAILABLE FOR PRE-SALE JULY 6 ON AMAZON AND ITUNES SEATTLE, WA – On the latest Seattle Symphony Media release featuring works by Berio, Boulez and Ravel, Music Director Ludovic Morlot and the Seattle Symphony present exhilarating performances of works by composers that mirror the innovative and vibrant spirit of the orchestra. The July 20 release of the “unforgettable, kaleidoscopic performance” (Seattle Times) of Berio’s Sinfonia featuring Grammy Award-winning ensemble Roomful of Teeth coupled with Boulez’s Notations I–IV for Orchestra and Ravel’s La valse create a sonic spectrum unlike any other. “These three composers drew on the Viennese tradition — Berio from Mahler, Boulez from Schoenberg, Ravel from J. Strauss — and expanded it to create amazingly rich orchestral scores through their incredible skill as orchestrators,” said Music Director Ludovic Morlot. “What a delight it was to work with Roomful of Teeth, whose outstanding versatility makes them ideal champions for this repertoire.” Berio’s Sinfonia was born out of the social and cultural upheavals of 1968 and 1969, demonstrating the profound power that music has to respond to cultural events. -

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana ABSTRACTS & PROGRAM NOTES updated October 30, 2015 Abeles, Harold see Ondracek-Peterson, Emily (The End of the Conservatory) Abeles, Harold see Jones, Robert (Sustainability and Academic Citizenship: Collegiality, Collaboration, and Community Engagement) Adams, Greg see Graf, Sharon (Curriculum Reform for Undergraduate Music Major: On the Implementation of CMS Task Force Recommendations) Arnone, Francesca M. see Hudson, Terry Lynn (A Persistent Calling: The Musical Contributions of Mélanie Bonis and Amy Beach) Bailey, John R. see Demsey, Karen (The Search for Musical Identity: Actively Developing Individuality in Undergraduate Performance Students) Baldoria, Charisse The Fusion of Gong and Piano in the Music of Ramon Pagayon Santos Recipient of the National Artist Award, Ramón Pagayon Santos is an icon in Southeast Asian ethnomusicological scholarship and composition. His compositions are conceived within the frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions and feature western and non- western elements, including Philippine indigenous instruments, Javanese gamelan, and the occasional use of western instruments such as the piano. Receiving part of his education in the United States and Germany (M.M from Indiana University, Ph. D. from SUNY Buffalo, studies in atonality and serialism in Darmstadt), his compositional style developed towards the avant-garde and the use of extended techniques. Upon his return to the Philippines, however, he experienced a profound personal and artistic conflict as he recognized the disparity between his contemporary western artistic values and those of postcolonial Southeast Asia. Seeking a spiritual reorientation, he immersed himself in the musics and cultures of Asia, doing fieldwork all over the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, resulting in an enormous body of work. -

Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice As Compositional Process in Berio's Sequenza I for Solo Flute

Chapter 11 Vestiges of Twelve-Tone Practice as Compositional Process in Berio’s Sequenza I for Solo Flute Irna Priore The ideal listener is the one who can catch all the implications; the ideal composer is the one who can control them. Luciano Berio, 18 August 1995 Introduction Luciano Berio’s first Sequenza dates from 1958 and was written for the Italian flutist Severino Gazzelloni (1919–92). The first Sequenza is an important work in many ways. It not only inaugurates the Sequenza series, but is also the third major work for unaccompanied flute in the twentieth century, following Varèse’s Density 21.5 (1936) and Debussy’s Syrinx (1913).1 Berio’s work for solo flute is an undeniable challenge for the interpreter because it is a virtuoso piece, it is written in proportional notation without barlines, and it is structurally ambiguous.2 It is well known that performances of this piece brought Berio much dissatisfaction, a fact that led to the publication of a new version by Universal Edition in 1992.3 This new edition was intended to supply a metrical understanding of the work, apparently lacking or too vaguely implied in the original score. However, while some aspects of the piece have been clarified by Berio himself, 1 A three-note chromatic motif has been observed running as a unifying thread in all three works. See Cynthia Folio, ‘Luciano Berio’s Sequenza for Flute: A Performance Analysis’, The Flutist Quarterly, 15/4 (1990), p. 18. 2 The observations regarding the difficulty of the work were compiled from informal interviews conducted between autumn 2003 and spring 2004 with professionals teaching in American universities and colleges, to whom I am indebted.