Defining Instrumental Collage Music in Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

2015 Regional Music Scholars Conference Abstracts Friday, March 27 Paper Session 1 1:00-3:05

2015 REGIONAL MUSIC SCHOLARS CONFERENCE A Joint Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory (RMSMT), Society for Ethnomusicology, Southwest Chapter (SEMSW), and Rocky Mountain Chapter of the American Musicological Society (AMS-RMC) School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, Colorado State University March 27 and 28, 2015 ABSTRACTS FRIDAY, MARCH 27 PAPER SESSION 1 1:00-3:05— NEW APPROACHES TO FORM (RMSMT) Peter M. Mueller (University of Arizona) Connecting the Blocks: Formal Continuity in Stravinsky’s Sérénade en La Phrase structure and cadences did not expire with the suppression of common practice tonality. Joseph Straus points out the increased importance of thematic contrast to delineate sections of the sonata form in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Igor Stravinsky exploited other musical elements (texture, range, counterpoint, dynamics, etc.) to delineate sections in his neoclassical works. While theorists have introduced large-scale formal approaches to Stravinsky’s works (block juxtaposition, stratification, etc.), this paper presents an examination of smaller units to determine how they combine to form coherence within and between blocks. The four movements of the Sérénade present unique variations of phrase construction and continuity between sections. The absence of clear tonic/dominant relationships calls for alternative formal approaches to this piece. Techniques of encirclement, enharmonic ties, and rebarring reveal methods of closure. Staggering of phrases, cadences, and contrapuntal lines aid coherence to formal segments. By reversing the order of phrases in outer sections, Stravinsky provides symmetrical “bookends” to frame an entire movement. Many of these techniques help to identify traditional formal units, such as phrases, periods, and small ternary forms. -

Musical Notations 3

F.A.P. May/June 1971 Musical Notations on Stamps: Part 3 By J. Posell Since my last article on this subject which appeared in FAP Journals (Vol. 14, 4 and 5), a number of stamps have been issued with musical notation which have aroused considerable interest and curiosity. Rather than waiting the five year period which I promised our readers, I have been prevailed upon to compile a listing of these issues now. Some of the information contained here has already been sent to different collectors who made inquiries of me; some of it has already appeared in print. However, it seems appropriate to include it all under one roof again and so I beg the indulgence of my friends who may find some of this reading repetitious. AJMAN Scott ??? Michel 427 A This issue was described in detail by this writer in the Western Stamp Collector for 16 May 1970. The issue consists of four stamps and a souvenir sheet all issued both perforated and imperforate. The imperforate stamps include the musical quotation both at top and bottom plus a picture of a violin in the border at right. The notation is strangely incorrect on all issues. The following information is extracted from the above article. The music on the Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) stamp is the opening chorale from the St. Matthew Passion (Ah dearest Jesu), Bach's most famous oratorio. This is originally written in the key of B minor but on the stamp it has been transposed down to the key of G minor. -

Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017

AAP: Music American nostalgia: Samuel Barber (1910-81), Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017 Aaron Copland • Parents immigrated to the US and opened a furniture store in Brooklyn • Youngest of five children • Began studying piano at age 13 • Studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) • The school of music at CUNY Queens College is named after him: Aaron Copland School of Music Career: • Composed – musical style incorporates Latin American (Brazilian, Cuban, Mexican), Jewish, Anglo-American, and African-American (jazz) sources • Conducted (1958-78) • Wrote essays about music • Visiting teaching positions (New School for Social Research, Henry Street Settlement, Harvard University) • Public lectures (Harvard’s Norton Professor of Poetics, 1951-52) Copland organized concerts that promoted the music of his peers: Marc Blitzstein (1905-64) Roy Harris (1898-1979) Paul Bowles (1910-99) Charles Ives (1874-1954) Henry Brant (1913-2008) Walter Piston (1894-1976) Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) Carl Ruggles (1876-1971) Israel Citkowitz (1909-74) Roger Sessions (1896-1985) Vivian Fine (1913-2000) Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) Copland was a mentor to younger composers: Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) Irving Fine (1914-62) David del Tredici (b. 1937) Lukas Foss (1922-2009) David Diamond (1915-2005) Barbara Kolb (b. 1939) Jacob Druckman (1928-96) William Schuman (1910-92) Elliott Carter (1908-2012) AAP: Music Selected works Orchestra Ballets (also published as orchestral suites) Music for the Theatre (1925) Billy the Kid -

Tonalitysince 1950

Tonality Since 1950 Tonality Since 1950 documents the debate surrounding one of the most basic technical and artistic resources of music in the later 20th century. The obvious flourishing of tonality – a return to key, pitch center, and consonance – in recent decades has undermi- ned received views of its disintegration or collapse ca. 1910, in- tensifying the discussion of music’s acoustical-theoretical bases, and of its broader cultural and metaphysical meanings. While historians of 20th-century music have often marginalized tonal practices, the present volume offers a new emphasis on emergent historical continuities. Musicians as diverse as Hindemith, the Beatles, Reich, and Saariaho have approached tonality from many different angles: as a figure of nostalgic longing, or as a universal law; as a quoted artefact of music’s sedimented stylistic past, or as a timeless harmonic resource. Essays by 15 leading contributors cover a wide repertoire of concert and pop/rock music composed Tonal in Europe and America over the past half-century. Tonality Since 1950 Since 1950 ISBN 978-3-515-11582-7 www.steiner-verlag.de Musikwissenschaft Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag Edited by Felix Wörner, TonaWörner / Scheideler/ Rupprecht liUllricht Scheideler and Philipy Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Franz Steiner Verlag Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

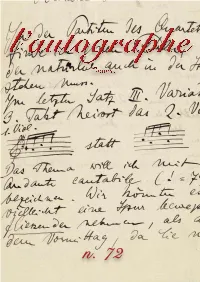

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. 1. Richard Adler (New York City, 1921 - Southampton, 2012) Autograph dedication signed on the frontispiece of the musical score of the popular song “Whatever Lola Wants” from the musical comedy “Damn Yankees” by the American composer and producer of several Broadway shows and his partner Jerry Ross. 5 pp. In fine condition. Countersigned with signature and dated “6/2/55” by the accordionist Muriel Borelli. $ 125/Fr. 115/€ 110 2. Franz Allers (Carlsbad, 1905 - Paradise, 1995) Photo portrait with autograph dedication and musical quotation signed, dated June 1961 of the Czech born American conductor of ballet, opera and Broadway musicals. (8 x 10 inch.). In fine condition. -

The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers' Solo Piano

International Education Studies; Vol. 14, No. 3; 2021 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers’ Solo Piano Works Used in Piano Education Sirin A. Demirci1 & Eda Nergiz2 1 Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey 2 State Conservatory Music Department, Giresun University, Turkey Correspondence: Sirin A. Demirci, Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 19, 2020 Accepted: November 6, 2020 Online Published: February 24, 2021 doi:10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 Abstract It is thought that to be successful in piano education it is important to understand how composers composed their solo piano works. In order to understand contemporary music, it is considered that the definition of today’s changing music understanding is possible with a closer examination of the ideas of contemporary composers about their artistic productions. For this reason, the qualitative research method was adopted in this study and the data obtained from the semi-structured interviews with 7 Turkish contemporary composers were analyzed by creating codes and themes with “Nvivo11 Qualitative Data Analysis Program”. The results obtained are musical elements of currents, styles, techniques, composers and genres that are influenced by contemporary Turkish composers’ solo piano works used in piano education. In total, 9 currents like Fluxus and New Complexity, 3 styles like Claudio Monteverdi, 5 techniques like Spectral Music and Polymodality, 5 composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Guillaume de Machaut and 9 genres like Turkish Folk Music and Traditional Greek are reached. -

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana ABSTRACTS & PROGRAM NOTES updated October 30, 2015 Abeles, Harold see Ondracek-Peterson, Emily (The End of the Conservatory) Abeles, Harold see Jones, Robert (Sustainability and Academic Citizenship: Collegiality, Collaboration, and Community Engagement) Adams, Greg see Graf, Sharon (Curriculum Reform for Undergraduate Music Major: On the Implementation of CMS Task Force Recommendations) Arnone, Francesca M. see Hudson, Terry Lynn (A Persistent Calling: The Musical Contributions of Mélanie Bonis and Amy Beach) Bailey, John R. see Demsey, Karen (The Search for Musical Identity: Actively Developing Individuality in Undergraduate Performance Students) Baldoria, Charisse The Fusion of Gong and Piano in the Music of Ramon Pagayon Santos Recipient of the National Artist Award, Ramón Pagayon Santos is an icon in Southeast Asian ethnomusicological scholarship and composition. His compositions are conceived within the frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions and feature western and non- western elements, including Philippine indigenous instruments, Javanese gamelan, and the occasional use of western instruments such as the piano. Receiving part of his education in the United States and Germany (M.M from Indiana University, Ph. D. from SUNY Buffalo, studies in atonality and serialism in Darmstadt), his compositional style developed towards the avant-garde and the use of extended techniques. Upon his return to the Philippines, however, he experienced a profound personal and artistic conflict as he recognized the disparity between his contemporary western artistic values and those of postcolonial Southeast Asia. Seeking a spiritual reorientation, he immersed himself in the musics and cultures of Asia, doing fieldwork all over the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, resulting in an enormous body of work. -

Polystylism and Narrative Potential in the Music of Alfred Schnittke

POLYSTYLISM AND NARRATIVE POTENTIAL IN THE MUSIC OF ALFRED SCHNITTKE by JEAN-BENOIT TREMBLAY B.Arts (education musicale), Universite Laval, 1999 B.Mus (mention en histoire), Universite Laval, 1999 M.Mus (musicologie), Universite Laval, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Music, emphasis in musicology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2007 © Jean-Benoit Tremblay, 2007 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the narrative potential created by polystylism in selected works of Alfred Schnittke. "Polystylism," the combination of many styles in a single work, is Schnittke's answer to a compositional crisis that he experienced as a young Soviet composer. Polystylistic works often present blunt juxtapositions of styles that cannot be explained by purely musical considerations. I argue that listeners, confronted with those stylistic gaps, instinctively attempt to resolve them by the construction of a narrative. Three works, each showing different approaches to polystylism, are examined. The Symphony No. 1, which constitutes a kind a polystylistic manifesto, presents a number of exact quotations of Beethoven, Grieg, Tchaikovsky and Chopin among others. It also makes uses of the Dies Irae and of various stylistic allusions. The result is a work in which Schnittke, asking how to write a Symphony, eventually kills the genre before resurrecting it. Elaborated from a fragment of a pantomime by Mozart, Mo^-Art is a reflection on the opposition between the old and the new, between the past and the present. The work builds upon the plurality of styles already present in Mozart's music. -

The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 Introduction Ladislav Vycpálek’S Suite for Solo Viola, Op

UNIVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Viola Stands Alone: The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 A document submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Jacob William Adams Committee in charge: Professor Helen Callus, Chair Professor Derek Katz Professor Paul Berkowitz December 2014 The document of Jacob William Adams is approved. Paul Berkowitz Derek Katz Helen Callus, Committee Chair ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research and writing would not have been possible without tremendous support and encouragement from several important people. Firstly, I must acknowledge the UCSB faculty members that comprise my committee: Helen Callus, Derek Katz, and Paul Berkowitz. All three have provided invaluable guidance, constructive feedback, and varied points of view to consider throughout the researching and writing process, and each of them has contributed significantly to my development as a musician-scholar. Beyond my committee members, I want to thank Carly Yartz, David Holmes, Tricia Taylor, and Patrick Chose. These various staff members of the UCSB Music Department have provided much needed assistance throughout my tenure as a graduate student in the department. Finally, I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my parents, David and Martha. They instilled a passion for music and an intellectual curiosity early and often in my life. They helped me see the connections in things all around me, encouraged me to work hard and probe deeper, and to examine how seemingly disparate things can relate to one another or share commonalities. It is thanks to them and their never-ending love and support that I have been able to accomplish what I have. -

Memory and Aesthetics: Study of Musical Quotations in Ives's and Crumb's Music

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2018, Vol. 8, No. 6, 852-879 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.06.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING Memory and Aesthetics: Study of Musical Quotations in Ives’s and Crumb’s Music LEUNG Tai-wai David Independant Scholar, Hong Kong China Throughout Western music history, pre-existing material has long been the aesthetic core of a new composition. Yet there has never been such an epoch as our time in which using pre-existing material, melodic quotation in particular, features so extensively in works of many of the composers. The aim of this paper is to investigate how the use of quoted tunes in a musical piece operates in an interwoven complex where time and space are of the essence. A quote is able to oscillate perpetually between one’s mental worlds of the memorable past and the imaginative present when it is highlighted enough to be recognizable from its surrounding context. Upon interpreting the use of quotation in various contexts, the aesthetic object, I argue, is the shift from original to quoted music, and vice versa. And listeners can respond aesthetically to the quotation itself even without knowledge of its provenance and textual or referential content. Keywords: aesthetics, collage, emotional response, flashback, imaginary world, memory, metaphor, musical borrowing, melodic quotation, quoted tune, real world, stream-of-consciousness, temporal level Introduction How is memory turned into art? For some, the process is almost spontaneous. A stroll in the meadows easily sparked the most spectacular sound picture in Ives’ orchestral set. A sail across the lake soon occasioned the opening of one of the most ambitious of all Mahler’s symphonic music. -

Opera in Miniature

Kurs: DA 4005 Självständigt arbete, 30 hp 2020 Konstnärlig masterexamen i musik, 120 hp Institutionen för komposition, dirigering och musikteori Handledare: Klas Nevrin Ryszard Alzin Opera in Miniature Around my piece Raport o stanie planety for four solo voices and ensemble Skriftlig reflektion inom självständigt arbete Det självständiga, konstnärliga arbetet finns dokumenterat i KMH:s digitala arkiv i Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1 1. Opera ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. The Genre .................................................................................................................... 4 1.1.1. The Paradox of Opera ......................................................................................... 4 1.1.2. Transformations of the Opera Genre ................................................................... 5 1.2. Opera in Miniature ...................................................................................................... 8 1.2.1. Connection with the Opera Genre ....................................................................... 8 1.2.2. The Ten Movements ............................................................................................ 9 2. Maximalism and Polystylism ............................................................................................. 14 2.1. Maximalism,