Narrativity in Postmodern Music: a Study of Selected Works of Alfred Schnittke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

The Crucifixion: Stainer's Invention of the Anglican Passion

The Crucifixion: Stainer’s Invention of the Anglican Passion and Its Subsequent Influence on Descendent Works by Maunder, Somervell, Wood, and Thiman Matthew Hoch Abstract The Anglican Passion is a largely forgotten genre that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modeled distinctly after the Lutheran Passion— particularly in its use of congregational hymns that punctuate and comment upon the drama—Anglican Passions also owe much to the rise of hymnody and small parish music-making in England during the latter part of the nineteenth century. John Stainer’s The Crucifixion (1887) is a quintessential example of the genre and the Anglican Passion that is most often performed and recorded. This article traces the origins of the genre and explores lesser-known early twentieth-century Anglican Passions that are direct descendants of Stainer’s work. Four works in particular will be reviewed within this historical context: John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary (1904), Arthur Somervell’s The Passion of Christ (1914), Charles Wood’s The Passion of Our Lord according to St Mark (1920), and Eric Thiman’s The Last Supper (1930). Examining these works in a sequential order reveals a distinct evolution and decline of the genre over the course of these decades, with Wood’s masterpiece standing as the towering achievement of the Anglican Passion genre in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The article concludes with a call for reappraisal of these underperformed works and their potential use in modern liturgical worship. A Brief History of the Passion Genre from the sung in plainchant, and this practice continued Medieval Era to the Eighteenth Century through the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. -

Bach Academy Bruges

ENGLISH Wed 24 Jan — Sun 28 Jan 2018 BACH BEWERKT BACH ACADEMY BRUGES Bach rearranged — 01 — Dear music lover Festival summary Welcome to this eighth Bach than composing for religious services: WED 24 JAN 2018 15.00 Concert hall 17.00 Chamber music hall seeking the essence of music, distilling out BELGIAN PREMIERE Oxalys & Bojan Cicic Academy, with a programme that its language as far as he was able. 19.15 Stadsschouwburg Dietrich Henschel All roads lead to Bach focuses on the parody. The last ten years of his life saw the Introduction by Gloria Schemelli’s Gesangbuch p. 20 composition of the second part of the Carlier (in Dutch) p. 10 Well-Tempered Clavier, the Goldberg 19.15 Chamber music hall As you undoubtedly know, Bach frequently Variations, the Von Himmel Hoch choral 20.00 Stadsschouwburg 17.00 Chamber music hall Introduction by Ignace drew on music by other composers or his variations, The Musical Offering, the Mass Mass B Christine Busch & Bossuyt (in Dutch) own earlier work to mould into new works of in B minor and The Art of the Fugue. None Béatrice Massin & Jörg Halubek his own. The Mass in B minor, for example, of these compositions was written on Compagnie Fêtes galantes Bach. Violin sonatas 20.00 Concert hall is a brilliant interweaving of largely commission. For these works, Bach was i.c.w. Cultuurcentrum Brugge p. 11 Collegium Vocale Gent refashioned parts of earlier cantatas with driven only by artistic inspiration. They So singen wir recht das earned him nothing, and only thirty copies 19.15 Chamber music hall Gratias newly-composed passages. -

Tezfiatipnal "

tezfiatipnal" THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Borodin Quartet MIKHAIL KOPELMAN, Violinist DMITRI SHEBALIN, Violist ANDREI ABRAMENKOV, Violinist VALENTIN BERLINSKY, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 25, 1990, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 .............................. PROKOFIEV Allegro sostenuto Adagio, poco piu animate, tempo 1 Allegro, andante molto, tempo 1 Quartet No. 3 (1984) .......................................... SCHNITTKE Andante Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, with Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 ...... BEETHOVEN Adagio, ma non troppo; allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alia danza tedesca: allegro assai Cavatina: adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge The Borodin Quartet is represented exclusively in North America by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, Inc., San Francisco. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twenty-eighth Concert of the lllth Season Twenty-seventh Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 ........................ SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev, born in Sontsovka, in the Ekaterinoslav district of the Ukraine, began piano lessons at age three with his mother, who also encouraged him to compose. It soon became clear that the child was musically precocious, writing his first piano piece at age five and playing the easier Beethoven sonatas at age nine. He continued training in Moscow, studying piano with Reinhold Gliere, and in 1904, entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Anatoly Lyadov, orchestration with Rimsky- Korsakov, and conducting with Alexander Tcherepnin. -

Dismantling the Time: a Theoretical and Practical Basis for Sinusoidal Deconstruction

Dismantling the time: a theoretical and practical basis for sinusoidal deconstruction Ángel Arranz Master Thesis Institute of Sonology Royal Conservatory of The Hague 2008 Music gives soul to the universe, wings to the thought, flying to the imagination, charm to the sadness, bliss and life to everything. (Plato) Aeterna Renovatio 2 Abstract “The basic purpose of this project is to build an auto-conductive non-harmonic musical system with nine instrumental parts and/or a live electronics field. One of the main properties is dispensability: any of the parts may be omitted without damage in the macrostructure. As the absence of some parts as the combinatorial variability of them do not affect the musical efficacy of the composition. Such a system will be possible thanks to the observation of some compositional conductive models of the past (Flemish polyphony) and some more present, as Xenakis’s stochastic music. Fundamentally, this task is made by means of ‘seeds’, minimal elemental shapes, which create the macro and micro levels of the work. In the first level of the composition, the macroform level, the seeds are implemented in a computer-assisted composition environment using the AC Toolbox program, where a graphics-based grammar is set on a discourse that is drawn in a unique stochastic gesture and later deconstructed. In the second level of composition, the microform level, the seed’s data are used as a controller of electronic gestures implemented in the Max/MSP program. The principal purpose of this level will be to enlarge the compositional domain and give an opportunity of extension to the physical possibilities of instruments, driving it towards the micro-sounds and other parallel temporal processes and having their own self-sufficient process inside the work”. -

UC Santa Barbara Continuing Lecturer Natasha

CONTACT: Adriane Hill Marketing and Communications Manager (805) 893-3230 [email protected] music.ucsb.edu FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / February 7, 2020 UC SANTA BARBARA CONTINUING LECTURER NATASHA KISLENKO TO PRESENT SOLO PIANO WORKS BY MOZART, CHOPIN, RACHMANINOFF, AND SCHNITTKE Internationally-renowned pianist to present solo piano works along with Lutosławski’s Variations on the GH theme by Paganini for two pianos with UC Santa Barbara Teaching Professor Sarah Gibson Santa Barbara, CA (February 7, 2020)—Natasha Kislenko, Continuing Lecturer of Keyboard at UC Santa Barbara, will present a solo piano recital on Friday, February 21, 2020 at 7:30 pm in Karl Geiringer Hall on the UC Santa Barbara campus. The program will include solo piano works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Frédéric Chopin, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Alfred Schnittke, plus a duo-piano work by Witold Lutosławski, featuring UC Santa Barbara Teaching Professor Sarah Gibson. Recognized by the Santa Barbara Independent for her “vividly expressive” interpretations and “virtuosity that left the audience exhilarated,” Kislenko offers unique concert programs and presentations to a worldwide community of music listeners. A prizewinner of several international piano competitions, she has extensively concertized in Russia, Germany, Italy, Spain, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Turkey, and across the Americas. A resident pianist of the Santa Barbara Symphony since 2010, she has been a featured soloist for the Shostakovich, Grieg, Clara Schumann, de Falla, and Mozart piano concerti, to great critical acclaim. Kislenko’s UC Santa Barbara program will open with Mozart’s Six Variations in F Major on “Salve tu, Domine” by G. Paisiello, K. 398. The theme of the work is taken from Mozart’s Italian contemporary Giovanni Paisiello’s opera, I filosofi immaginari (The Imaginary Philosophers), one of Paisiello’s most recognized opere buffe, written for the court of Catherine II of Russia. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Tonalitysince 1950

Tonality Since 1950 Tonality Since 1950 documents the debate surrounding one of the most basic technical and artistic resources of music in the later 20th century. The obvious flourishing of tonality – a return to key, pitch center, and consonance – in recent decades has undermi- ned received views of its disintegration or collapse ca. 1910, in- tensifying the discussion of music’s acoustical-theoretical bases, and of its broader cultural and metaphysical meanings. While historians of 20th-century music have often marginalized tonal practices, the present volume offers a new emphasis on emergent historical continuities. Musicians as diverse as Hindemith, the Beatles, Reich, and Saariaho have approached tonality from many different angles: as a figure of nostalgic longing, or as a universal law; as a quoted artefact of music’s sedimented stylistic past, or as a timeless harmonic resource. Essays by 15 leading contributors cover a wide repertoire of concert and pop/rock music composed Tonal in Europe and America over the past half-century. Tonality Since 1950 Since 1950 ISBN 978-3-515-11582-7 www.steiner-verlag.de Musikwissenschaft Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag Edited by Felix Wörner, TonaWörner / Scheideler/ Rupprecht liUllricht Scheideler and Philipy Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Tonality Since 1950 Edited by Felix Wörner, Ullrich Scheideler and Philip Rupprecht Franz Steiner Verlag Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

Schnittke CD Catalogue

Ivahskin-Schnittke Archive Compact Discs Archive Year of CD Title Schnittke pieces included Performers Label Recording Recording/ Number on CD Number release 1 String trios - Schnittke, String Trio Krysa, O: Kuchar, T; - - - Penderecki, Gubaidulina Ivashkin, A. 2 Webber, Schumman, Sonata for Violin No.2 Kremer, G; Gavrilov, A; Muti, Olympia 501079 1982/1979 Hindesmith, Schnittke (Quasi una sonata) R. Symponic Prelude Schnittke - Symphonic Norrkoping Symphony (1993)/Symphony no.8 3 prelude, Symphony no. 8, Orchestra (Lu Jia - BIS BIS-CD-1217 2005 (1994)/ For Liverpool For Liverpool Conductor) (1994) Schnittke - Minnesang, Minnesang, Concerto for 4 Concerto for mixed choir mixed choir Danish Choir - - - Schnittke - Lux Aeterna Lux Aeterna (Requiem of (Requiem of 5 reconciliation) Krakow Chamber Choir - - 1995 reconciliation) 6 [number not in use] 7 [number not in use] 8 Rastakov, A (Composer) Schnittke: Ritual - (K)ein Ritual/ (K)ein sommernachtstraum - Sommernachtstraum/ Malmo SymphonyOrchestra 9 Passacaglia - Seid nuchten Passacaglia/ Seid nuchtern BIS BIS-CD-437 1989 und wachet und wachtet The State Chamber Choir of the USSR (Dof-Fonskaya, E - 10 Schnittke - Concerto for Concerto for choir in four Soprano; Polyanky, V - Arteton VICC-51 1991 choir in four movements movements Conductor) BBC Symphony Orchestra Alfred Schnittke - Symphony no.2 'St (conducted by Carlton 15656 1997 Symphony no. 2 'St Florian'/ Pas de quatre Rozhdestvensky, G) & BBC Classics 91962 11 Florian' Symphony Chorus (conducted by Cleobury, S) 12 [number not in use] 13 [number not in use] Ivahskin-Schnittke Archive Compact Discs Three madrigals (Sur une Soloists Ensemble of the Denisov, Schnittke, Mobile 14 etoile, Entfernung, Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra MFCD 869 1983 Gubaidulina, Mansurian Fidelity Reflection) Sound Lab The USSR Ministry of Culture Orchestra 15 A Schnittke - Symphony Symphony no.1 Melodiya SUCD 10- 1990/1987 (conducted by no. -

The Pacifica Quartet Simin Ganatra, Violin Sibbi Berhardsson, Violin Masumi Per Rostad, Viola Brandon Vamos, Cello

62nd Concert Series 2015-2016 is pleased to present The Pacifica Quartet Simin Ganatra, violin Sibbi Berhardsson, violin Masumi Per Rostad, viola Brandon Vamos, cello Saturday, May 14, 2016 Sleepy Hollow High School, Sleepy Hollow, New York President: Betsy Shaw Weiner, Croton Vice President: Board Associates: William Altman, Croton Keith Austin, Briarcliff Manor Secretary: George Drapeau, Armonk Susan Harris, Ossining Nyla Isele, Croton Treasurer: Edwin Leventhal, Pomona Marc Auslander, Millwood Board of Directors: Klaus Brunnemann, Briarcliff Manor Howard Cohen, Cortlandt Manor Raymond Kaplan, Yorktown Heights David Kraft, Briarcliff Manor Tom Post, Mt. Kisco Rosella Ranno, Briarcliff Manor Who We Are Friends of Music Concerts, Inc. is an award-winning, non-profit, volunteer organization that brings to Westchester audiences world-renowned ensembles and distinguished younger musicians chosen from among the finest artists in today’s diverse world of chamber music. Through our Partnership in Education program in public schools, and free admission to our six-concert season for those 18 years of age and under, we give young people throughout the county enhanced exposure to and appreciation of classical music, building audiences of the future. We need additional helping hands to carry out our mission. Do consider joining the volunteers listed above. Call us at 914-861-5080 or contact us on our website (see below); we can discuss several specific areas in which assistance is needed. Acknowledgments Our concerts are made possible, in part, by an ArtsWestchester Program Support grant made with funds received from Westchester County Government, and by a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

Alfred Schnittke Concerto Grosso No.1 Symphony No.9

alfred schnittke Concerto grosso No.1 SHARON BEZALY FLUTE CHRISTOPHER COWIE OBOE Symphony No.9 CAPE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA OWAIN ARWEL HUGHES CAPE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA KAAPSE FILHARMONIESE ORKES I-okhestra yomculo yaseKoloni BIS-CD-1727 BIS-CD-1727_f-b.indd 1 09-05-18 16.16.53 BIS-CD-1727 Alf:booklet 11/5/09 12:58 Page 2 SCHNITTKE, Alfred (1934–98) Concerto grosso No. 1 (1977) (Sikorski) 27'13 Version for flute, oboe, harpsichord, prepared piano and string orchestra (1988) world première recording 1 I. Preludio. Andante 4'46 2 II. Toccata. Allegro 4'33 3 III. Recitativo. Lento 6'39 4 IV. Cadenza 2'11 5 V. Rondo. Agitato 6'45 6 VI. Postludio. Andante 2'13 Sharon Bezaly flute · Christopher Cowie oboe Grant Brasler harpsichord · Albert Combrink piano Symphony No. 9 (1997) (Sikorski) 33'19 Reconstruction by Alexander Raskatov (2006) 7 I. [Andante] 18'03 8 II. Moderato 7'57 9 III. Presto 7'01 TT: 61'24 Cape Philharmonic Orchestra Farida Bacharova leader Owain Arwel Hughes conductor 2 BIS-CD-1727 Alf:booklet 11/5/09 12:58 Page 3 lfred Schnittke (1934–98) needs very little introduction. His music has been performed countless times all around the world and recorded on A numerous compact discs released by different companies. His major com positions – nine symphonies, three operas, ballets, concertos, concerti grossi, sonatas for various instruments – have been heard on every continent. In Schnitt - ke’s music we find a mixture of old and new styles, of modern, post-modern, clas sical and baroque ideas. It reflects a very complex, peculiar and fragile men - tality of the late twentieth century. -

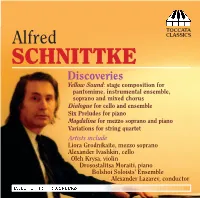

Toccata Classics TOCC 0091 Notes

TOCCATA Alfred CLASSICS SCHNITTKE Discoveries Yellow Sound: stage composition for pantomime, instrumental ensemble, soprano and mixed chorus Dialogue for cello and ensemble Six Preludes for piano Magdalina for mezzo soprano and piano Variations for string quartet Artists include Liora Grodnikaite, mezzo soprano Alexander Ivashkin, cello Oleh Krysa, violin Drosostalitsa Moraiti, piano Bolshoi Soloists’ Ensemble Alexander Lazarev, conductor SCHNITTKE DISCOVERIES by Alexander Ivashkin This CD presents a series of ive works from across Alfred Schnittke’s career – all of them unknown to the wider listening public but nonetheless giving a conspectus of the evolution of his style. Some of the recordings from which this programme has been built were unreleased, others made specially for this CD. Most of the works were performed and recorded from photocopies of the manuscripts held in Schnittke’s family archive in Moscow and in Hamburg and at the Alfred Schnittke Archive in Goldsmiths, University of London. Piano Preludes (1953–54) The Piano Preludes were written during Schnittke’s years at the Moscow Conservatory, 1953–54; before then he had studied piano at the Moscow Music College from 1949 to 1953. An advanced player, he most enjoyed Rachmaninov and Scriabin, although he also learned and played some of Chopin’s Etudes as well as Rachmaninov’s Second and the Grieg Piano Concerto. It was at that time that LPs irst became available in the Soviet Union, and so he was able to listen to recordings of Wagner’s operas and Scriabin’s orchestral music. The piano style in the Preludes is sometimes very orchestral, relecting his interest in the music of these composers.