Toccata Classics TOCC 0091 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAN 9722 Front.Qxd 25/7/07 3:07 Pm Page 1

CHAN 9722 Front.qxd 25/7/07 3:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 9722 CHANDOS Schnittke (K)ein Sommernachtstraum Cello Concerto No. 2 Alexander Ivashkin cello Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valeri Polyansky CHAN 9722 BOOK.qxd 25/7/07 3:08 pm Page 2 Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998) Cello Concerto No. 2* 42:00 1 I Moderato – 3:20 2 II Allegro 9:34 3 III Lento – 8:26 4 IV Allegretto mino – 4:34 5 V Grave 16:05 6 10:37 Nigel LuckhurstNigel (K)ein Sommernachtstraum (Not) A Midsummer Night’s Dream TT 52:50 Alexander Ivashkin cello* Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valeri Polyansky Alfred Schnittke 3 CHAN 9722 BOOK.qxd 25/7/07 3:08 pm Page 4 us to a point where nothing is single-faced ‘Greeting Rondo’ with elements from the First Alfred Schnittke: Cello Concerto No. 2/(K)ein Sommernachtstraum and everything is doubtful and double-folded. Symphony creeping into it; one can hear all The fourth movement is a new and last the sharp polystylistic shocking contrasts outburst of activity, of confrontation between similar to Schnittke’s First Symphony in The Second Cello Concerto (1990) is one of different phases and changes as if through a hero (the soloist) and a mob (the orchestra). condensed form here. (K)ein Sommernachts- Schnittke’s largest compositions. The musical different ages. The first subject is excessively Again, two typical elements are juxtaposed traum, written just before the composer’s fatal palate of the Concerto is far from simple, and active and turbulent, the second more here with almost cinematographical clarity: illness began to hound him, is one of his last the cello part is fiendishly difficult. -

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics is exploring it. To link label and listener directly we run the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you, free on joining, two CDs, a Toccata Press book or a number of album downloads (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases as CDs or downloads, as you prefer. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. -

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, Conductor Alexei Grynyuk, Piano

Sunday, March 26, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Theodore Kuchar, conductor Alexei Grynyuk, piano PROGRAM Giuseppe VERDI (1813 –1901) Overture to La forza del destino Sergei PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 Andante – Allegro Tema con variazioni Allegro, ma non troppo INTERMISSION Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH (1906 –1975) Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 Moderato – Allegro non troppo Allegretto Largo Allegro non troppo THE ORcHESTRA National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine Volodymyr Sirenko, artistic director & chief conductor Theodore Kuchar, conductor laureate First Violins cellos Bassoons Markiyan Hudziy, leader Olena Ikaieva, principal Taras Osadchyi, principal Gennadiy Pavlov, sub-leader Liliia Demberg Oleksiy Yemelyanov Olena Pushkarska Sergii Vakulenko Roman Chornogor Svyatoslava Semchuk Tetiana Miastkovska Mykhaylo Zanko Bogdan Krysa Tamara Semeshko Anastasiya Filippochkina Mykola Dorosh Horns Roman Poltavets Ihor Yarmus Valentyn Marukhno, principal Oksana Kot Ievgen Skrypka Andriy Shkil Olena Poltavets Tetyana Dondakova Kostiantyn Sokol Valery Kuzik Kostiantyn Povod Anton Tkachenko Tetyana Pavlova Boris Rudniev Viktoriia Trach Basses Iuliia Shevchenko Svetlana Markiv Volodymyr Grechukh, principal Iurii Stopin Oleksandr Neshchadym Trumpets Viktor Andriiichenko Oleksandra Chaikina Viktor Davydenko, principal Oleksii Sechen Yuri і Kornilov Harps Grygorii Кozdoba Second Violins Nataliia Izmailova, principal Dmytro Kovalchuk Galyna Gornostai, principal Diana Korchynska Valentyna -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Youtube's Classical Music Star Valentine Lisitsa Comes To

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE USE YouTube’s classical music star Valentine Lisitsa comes to Edinburgh’s Usher Hall Sunday Classics: Russian Philharmonic of Novosibirsk 3:00pm, Sunday 12 May 2019 Thomas Sanderling - Conductor Valentina Lisitsa - Piano Rimsky-Korsakov - Capriccio espagnol Rachmaninov - Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition Images available to download here Powerhouse all-Russian programme including Rachmaninov’s tender take on Paganini YouTube sensation Valentina Lisitsa is nothing less than a modern marvel. A brilliant pianist of the Russian old school who plays with fiery intensity and profound insight, she is also a musical evangelist who has taken classical music to millions through her online videos. Having posted her first video on YouTube in 2007, viewing figures soon exploded and more videos followed. The foundations of a social media-driven career unparalleled in the history of classical music were laid. Her YouTube channel now boasts more than 516,000 subscribers and over 200 million views. No wonder she’s in demand right across the world: her unprecedented global stardom is matched by her breath-taking playing. Lisitsa has long adored the romance and power of Rachmaninov and following her electrifying performance of his Third Piano Concerto at the Usher Hall in 2018, she makes a welcome return with the passionate Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Niccolò Paganini’s famous piece has been adored and interpreted by many a composer, including Brahms, but it’s Rachmaninov’s take on the classic that sees it as its tenderest, and wittiest. He moulds the main theme into musical styles and interpretations previously unheard, and there is no finer pianist to bring this to the Usher Hall than Valentina Lisitsa. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1989, No.12

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.. a fraternal non-profit association rainian Weekly Vol. LVIl No. 12 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 19, 1989 50 cents Lviv residents protest unjust elections Dzyuba focuses on Ukrainian language's as thousands march through city center perilous situation in Edmonton speech JERSEY CITY, N.J. - Thousands while two local police chiefs using by Marco Levytsky Pavlychko and myself. Therefore, I can of Lviv residents gathered on March 12 megaphones ordered the people to leave Editor, Ukrainian News of Edmonton tell you first hand, that it looks like this in the city center for a pre-elections the area. bill will indeed be made into law. The meeting which turned into an angry Meanwhile several police units, EDMONTON - Ivan Dzyuba, au government is receiving tens of thou demonstration after local police vio coming from all directions, surrounded thor of "Internationalism or Russifica- sands of letters that demand that lently attempted to scatter the crowd, the square and forced the crowd away tion?," focused his remarks here on Ukrainian be made into the official reported the External Representation from it and toward the city arsenal and March 3 on the perilous situation of the language of the republic," Mr. Dzyuba of the Ukrainian Helsinki Union last regional party committee headquarters. Ukrainian language, noting, however, said, speaking through an interpreter. week. Some people panicked and fell on the that "after decades and centuries of "We do not require such a law in Thousands of people had already pavement. The militiamen reportedly being suppressed and rooted out," the order to discriminate against other gathered at noon for the public meeting kicked them, while those who protested language may 'linally take its place in languages, just that the Ukrainian lan about the March 26 elections to the new were grabbed and shoved into police the world" after the Ukrainian SSR guage — after decades and centuries of Soviet parliament, which was scheduled cars. -

Tezfiatipnal "

tezfiatipnal" THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Borodin Quartet MIKHAIL KOPELMAN, Violinist DMITRI SHEBALIN, Violist ANDREI ABRAMENKOV, Violinist VALENTIN BERLINSKY, Cellist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, FEBRUARY 25, 1990, AT 4:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 .............................. PROKOFIEV Allegro sostenuto Adagio, poco piu animate, tempo 1 Allegro, andante molto, tempo 1 Quartet No. 3 (1984) .......................................... SCHNITTKE Andante Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, with Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 ...... BEETHOVEN Adagio, ma non troppo; allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alia danza tedesca: allegro assai Cavatina: adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge The Borodin Quartet is represented exclusively in North America by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, Inc., San Francisco. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twenty-eighth Concert of the lllth Season Twenty-seventh Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 92 ........................ SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891-1953) Sergei Prokofiev, born in Sontsovka, in the Ekaterinoslav district of the Ukraine, began piano lessons at age three with his mother, who also encouraged him to compose. It soon became clear that the child was musically precocious, writing his first piano piece at age five and playing the easier Beethoven sonatas at age nine. He continued training in Moscow, studying piano with Reinhold Gliere, and in 1904, entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied harmony and counterpoint with Anatoly Lyadov, orchestration with Rimsky- Korsakov, and conducting with Alexander Tcherepnin. -

Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Joseph Szigeti: Their Contributions to the Violin Repertoire of the Twentieth Century Jae Won (Noella) Jung

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Joseph Szigeti: Their Contributions to the Violin Repertoire of the Twentieth Century Jae Won (Noella) Jung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC JASCHA HEIFETZ, DAVID OISTRAKH, JOSEPH SZIGETI: THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE VIOLIN REPERTOIRE OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY By Jae Won (Noella) Jung A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Jae Won (Noella) Jung All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Jae Won (Noella) Jung on March 2, 2007. ____________________________________ Karen Clarke Professor Directing Treatise ____________________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ Alexander Jiménez Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor, Professor Karen Clarke, for her guidance and support during my graduate study at FSU and I am deeply grateful for her advice and suggestions on this treatise. I would also like to thank the rest of my doctoral committee, Professor Jane Piper Clendinning and Professor Alexander Jiménez for their insightful comments. This treatise would not have been possible without the encouragement and support from my family. I thank my parents for their unconditional love and constant belief, my sister for her friendship, and my nephew Jin Sung for his precious smile. -

Learning from the Best Conductors, Needs Little Introduction Born in Moscow in 1945, Lazarev Came from a Family in the Classical Music Community

The Man Behind The Legend Alexander Lazarev is spoken of in the same breath as some of the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Bolshoi Symphony Orchestra. This month, the Russian conductor will lead the Symphony Orchestra of India in a two-evening programme at the NCPA. By Beverly Pereira lexander Lazarev, one of Russia’s foremost Learning from the best conductors, needs little introduction Born in Moscow in 1945, Lazarev came from a family in the classical music community. But with no musical roots to speak of. Yet, he forged a an insight into his career and formative deep connection with the world of classical music years is imperative to understanding the from a young age. He was only 14 when he started to profoundA grasp he has on both the historical Russian attend operas and concerts on a regular basis. It was musical tradition and contemporary music by Russian the year 1959, a golden period for Soviet classical and foreign composers. Lazarev’s repertoire, best music, when composers like Sviatoslav Richter and described as innovative in its scope, ranges from the David Oistrakh were at the height of their musical 18th century to the avant-garde. careers. Lazarev says he tried to absorb as much Masterful in the music of composers from the music as he could during this period, adding that he Russian tradition, his performances are simultaneously remembers the excitement of experiencing visiting insightful, enterprising and authentic. As a uniquely orchestras led by foreign conductors, such as empathetic interpreter of Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Zubin Mehta. Rimsky-Korsakov and Prokofiev, he firmly believes Lazarev received his musical education at two of in equipping oneself with the holistic understanding Russia’s most prestigious institutions. -

Biographies of Composers & Presenters

BIOGRAPHIES OF COMPOSERS & PRESENTERS Admiral, Roger Canadian pianist Roger Admiral performs solo and chamber music repertoire spanning the 18th through the 21st century. Known for his dedication to contemporary music, Roger has commissioned and premiered many new compositions. He works regularly with UltraViolet (New Music Edmonton) and Aventa Ensemble (Victoria), and performs as part of Kovalis Duo with Montreal percussionist Philip Hornsey. Roger also coaches contemporary chamber music at the University of Alberta. Recent performances include Gyorgy Ligeti’s Piano Concerto with the Victoria Symphony Orchestra, the complete piano works of Iannis Xenakis for Vancouver New Music, a recital with baritone Nathan Berg at Lincoln Center’s Great Performers Series (New York City), and recitals for Curto-Circuito de Música Contemporânea Brazil with saxophonist Allison Balcetis, as well as solo recitals in Bratislava, Budapest, and Wroclaw. Roger can be heard on CD recordings of piano music by Howard Bashaw (Centrediscs) and Mark Hannesson (Wandelweiser Editions). Alexander, Justin Justin Alexander is an Assistant Professor of Music at Virginia Commonwealth University where he teaches Applied Percussion Lessons, Percussion Methods and Techniques, Introduction to World Musical Styles, Music and Dance Forms, and directs the VCU Percussion Ensemble. Justin is a founding member of Novus Percutere, with percussionist Dr. Luis Rivera, and The AarK Duo, with flutist Dr. Tabatha Easley. Recent highlights include collaborative performances in Sweden, Australia, the Percussive Arts Society International Convention, and at the 6th International Conference on Music and Minimalism in Knoxville, Tennessee. As a soloist, Justin focuses on the creation of new works for percussion through commissions and compositions, specifically focusing on post-minimalist/process/iterative keyboard music, non-western percussion, and drum set. -

TOCC0550DIGIBKLT.Pdf

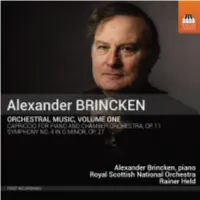

A FEW PARAGRAPHS ON ME AND MY MUSIC by Alexander Brincken As a Swiss citizen by choice, I have produced compositions which represent a strange cultural phenomenon. The strangeness was already predestined by my ethnic origin: my forebears include Germans (the Barons von den Brincken from Courland), Russians (Titov) and Georgians (Mrevlov/Mrevlischvili). These genetic factors seem to have determined my musical predispositions unconsciously. The circumstances of my intellectual development also contributed to this strangeness. I was born in 1952 in the Russian city of St Petersburg (then Leningrad in the Soviet Union), the most European metropolis in Russia. My artistic awareness as a budding composer was marked by the very city-scape of this former capital of Tsarist Russia, the defining built landmarks of which were designed by western European Baroque and Classical architects to the almost total exclusion of any authentic Russian elements. Moreover, I was trained at the elite musical establishment of Leningrad, the Special Music School of the Leningrad Conservatoire, where I mostly studied works of Baroque, Classical and Romantic German masters from Bach through the Viennese classics up to Schumann and Brahms. The only exception was familiarity with Rachmaninov’s music. My musical development was heavily influenced by regular visits in the 1960s and ’70s to the Leningrad Philharmonic, where Bruckner symphonies and Richard Strauss tone-poems made a formative impression. I must also mention two shattering experiences in the late 1960s: a visit by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic in a Beethoven programme, and the performance of Bach’s B minor Mass by the Munich Bach Ensemble under Karl Richter. -

Rsno.Org.Uk Rsno.Org.Uk/SEASON1516

2015:16 USHER HALL, EDINBURGH rsno.org.uk rsno.org.uk/SEASON1516 Subscribe SCOTLAND’S AND SAVE NATIONAL Save up to 35% when you subscribe to the Season! Simply choose a minimum of four concerts and you can start saving money. Book ORCHESTRA today using the pull-out booking form at the centre of the brochure. Celebrating 125 years of great music! Exclusive reception In 2016 the RSNO Subscribe to all eighteen Season concerts and you will receive an invitation to an exclusive reception with RSNO reaches an exciting Principal Timpanist Martin Gibson. milestone in its history – its 125th birthday! Since 1891 the Orchestra has enjoyed performing PETER OUNDJIAN BIRTHDAY BOYS: across Scotland and CONDUCTS CHORAL PROKOFIEV AND MASTERPIECES PORTER beyond with some of the We couldn’t celebrate 125 The RSNO isn’t alone years of great music without celebrating 125 years finest musicians of the the wonderful singers of the of glorious music. Sergei RSNO Chorus. Music Director Prokofiev and Cole Porter were day – and this Season we Peter Oundjian directs three also born in 1891 and so we’ll continue that tradition. large-scale choral masterpieces be sharing some of their finest throughout the Season. Make music with you across the Join us as we celebrate sure you don’t miss Mahler’s Season. Prokofiev’s Cinderella Resurrection Symphony, and Romeo and Juliet both our birthday and look Vaughan Williams’ Sea feature, and we’re especially Symphony and Beethoven’s thrilled that Nikolai Lugansky forward to another 125 Ninth Symphony Choral, which is joining us to perform all five brings the first half of our of Prokofiev’s piano concertos years of great music.