TOCC0550DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Youtube's Classical Music Star Valentine Lisitsa Comes To

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE USE YouTube’s classical music star Valentine Lisitsa comes to Edinburgh’s Usher Hall Sunday Classics: Russian Philharmonic of Novosibirsk 3:00pm, Sunday 12 May 2019 Thomas Sanderling - Conductor Valentina Lisitsa - Piano Rimsky-Korsakov - Capriccio espagnol Rachmaninov - Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition Images available to download here Powerhouse all-Russian programme including Rachmaninov’s tender take on Paganini YouTube sensation Valentina Lisitsa is nothing less than a modern marvel. A brilliant pianist of the Russian old school who plays with fiery intensity and profound insight, she is also a musical evangelist who has taken classical music to millions through her online videos. Having posted her first video on YouTube in 2007, viewing figures soon exploded and more videos followed. The foundations of a social media-driven career unparalleled in the history of classical music were laid. Her YouTube channel now boasts more than 516,000 subscribers and over 200 million views. No wonder she’s in demand right across the world: her unprecedented global stardom is matched by her breath-taking playing. Lisitsa has long adored the romance and power of Rachmaninov and following her electrifying performance of his Third Piano Concerto at the Usher Hall in 2018, she makes a welcome return with the passionate Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Niccolò Paganini’s famous piece has been adored and interpreted by many a composer, including Brahms, but it’s Rachmaninov’s take on the classic that sees it as its tenderest, and wittiest. He moulds the main theme into musical styles and interpretations previously unheard, and there is no finer pianist to bring this to the Usher Hall than Valentina Lisitsa. -

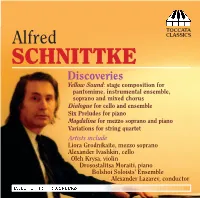

Toccata Classics TOCC 0091 Notes

TOCCATA Alfred CLASSICS SCHNITTKE Discoveries Yellow Sound: stage composition for pantomime, instrumental ensemble, soprano and mixed chorus Dialogue for cello and ensemble Six Preludes for piano Magdalina for mezzo soprano and piano Variations for string quartet Artists include Liora Grodnikaite, mezzo soprano Alexander Ivashkin, cello Oleh Krysa, violin Drosostalitsa Moraiti, piano Bolshoi Soloists’ Ensemble Alexander Lazarev, conductor SCHNITTKE DISCOVERIES by Alexander Ivashkin This CD presents a series of ive works from across Alfred Schnittke’s career – all of them unknown to the wider listening public but nonetheless giving a conspectus of the evolution of his style. Some of the recordings from which this programme has been built were unreleased, others made specially for this CD. Most of the works were performed and recorded from photocopies of the manuscripts held in Schnittke’s family archive in Moscow and in Hamburg and at the Alfred Schnittke Archive in Goldsmiths, University of London. Piano Preludes (1953–54) The Piano Preludes were written during Schnittke’s years at the Moscow Conservatory, 1953–54; before then he had studied piano at the Moscow Music College from 1949 to 1953. An advanced player, he most enjoyed Rachmaninov and Scriabin, although he also learned and played some of Chopin’s Etudes as well as Rachmaninov’s Second and the Grieg Piano Concerto. It was at that time that LPs irst became available in the Soviet Union, and so he was able to listen to recordings of Wagner’s operas and Scriabin’s orchestral music. The piano style in the Preludes is sometimes very orchestral, relecting his interest in the music of these composers. -

Learning from the Best Conductors, Needs Little Introduction Born in Moscow in 1945, Lazarev Came from a Family in the Classical Music Community

The Man Behind The Legend Alexander Lazarev is spoken of in the same breath as some of the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Bolshoi Symphony Orchestra. This month, the Russian conductor will lead the Symphony Orchestra of India in a two-evening programme at the NCPA. By Beverly Pereira lexander Lazarev, one of Russia’s foremost Learning from the best conductors, needs little introduction Born in Moscow in 1945, Lazarev came from a family in the classical music community. But with no musical roots to speak of. Yet, he forged a an insight into his career and formative deep connection with the world of classical music years is imperative to understanding the from a young age. He was only 14 when he started to profoundA grasp he has on both the historical Russian attend operas and concerts on a regular basis. It was musical tradition and contemporary music by Russian the year 1959, a golden period for Soviet classical and foreign composers. Lazarev’s repertoire, best music, when composers like Sviatoslav Richter and described as innovative in its scope, ranges from the David Oistrakh were at the height of their musical 18th century to the avant-garde. careers. Lazarev says he tried to absorb as much Masterful in the music of composers from the music as he could during this period, adding that he Russian tradition, his performances are simultaneously remembers the excitement of experiencing visiting insightful, enterprising and authentic. As a uniquely orchestras led by foreign conductors, such as empathetic interpreter of Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Zubin Mehta. Rimsky-Korsakov and Prokofiev, he firmly believes Lazarev received his musical education at two of in equipping oneself with the holistic understanding Russia’s most prestigious institutions. -

Rsno.Org.Uk Rsno.Org.Uk/SEASON1516

2015:16 USHER HALL, EDINBURGH rsno.org.uk rsno.org.uk/SEASON1516 Subscribe SCOTLAND’S AND SAVE NATIONAL Save up to 35% when you subscribe to the Season! Simply choose a minimum of four concerts and you can start saving money. Book ORCHESTRA today using the pull-out booking form at the centre of the brochure. Celebrating 125 years of great music! Exclusive reception In 2016 the RSNO Subscribe to all eighteen Season concerts and you will receive an invitation to an exclusive reception with RSNO reaches an exciting Principal Timpanist Martin Gibson. milestone in its history – its 125th birthday! Since 1891 the Orchestra has enjoyed performing PETER OUNDJIAN BIRTHDAY BOYS: across Scotland and CONDUCTS CHORAL PROKOFIEV AND MASTERPIECES PORTER beyond with some of the We couldn’t celebrate 125 The RSNO isn’t alone years of great music without celebrating 125 years finest musicians of the the wonderful singers of the of glorious music. Sergei RSNO Chorus. Music Director Prokofiev and Cole Porter were day – and this Season we Peter Oundjian directs three also born in 1891 and so we’ll continue that tradition. large-scale choral masterpieces be sharing some of their finest throughout the Season. Make music with you across the Join us as we celebrate sure you don’t miss Mahler’s Season. Prokofiev’s Cinderella Resurrection Symphony, and Romeo and Juliet both our birthday and look Vaughan Williams’ Sea feature, and we’re especially Symphony and Beethoven’s thrilled that Nikolai Lugansky forward to another 125 Ninth Symphony Choral, which is joining us to perform all five brings the first half of our of Prokofiev’s piano concertos years of great music. -

Download Booklet

570406bk USA 12/7/07 7:36 pm Page 5 8.570406 Royal Scottish National Orchestra British Piano Concerto Foundation Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being British Piano Concertos DDD granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Britain shares with the United States an extraordinary willingness to welcome and embrace the Europe’s leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include traditions of foreign cultures. Our countries comprise the world’s two greatest ‘melting pots’, and, as Sir John Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, a result, the artistic appreciation of our people has been possibly the most catholic and least nepotistic Neeme Järvi, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, in the world. This tradition is one that we may be extremely proud of. In the case of music, it is John who served as Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane certainly one of the reasons for my own initial inspiration to become a musician and to embrace as Denève was appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first Naxos recording, which couples Roussel’s Symphony many different styles and periods as reasonably possible in one lifetime. No. 3 with the complete ballet Bacchus et Ariane (8.570245) was released in May 2007. The orchestra made an Perhaps as a result of this very enviable virtue, however, we do have a tendency to underrate the GARDNER important contribution to the authoritative Naxos series of Bruckner Symphonies under the late Georg Tintner, and artistic traditions of our own wonderful culture. -

Prokofiev Violin Concerto No

PROKOFIEV VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 SYMPHONY NO. 3 CHOUT RÊVES ALEXANDER LAZAREV conductor VADIM REPIN violin SIMON CALLOW narrator LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA SERGEI PROKOFIEV The First World War and its aftermath played I represented in the past and what I have now havoc with the hopes and dreams of the young become.’ Prokofiev. Up to 1915, his path seemed easy and assured: from the creation of snappy piano Perhaps Prokofiev did not revise the miniatures and an early symphony in 1908 to work simply because it represents that the one-act ballet commissioned by Diaghilev impressionistic, late-romantic vein so well, and several weeks before war broke out, all went because the orchestration – including triple well. It was with incredible confidence, not woodwind, six horns and two harps – is, for to say clairvoyance, that Prokofiev declared in the piece in question, unimprovable. In his that year, ‘I am in no doubt that given time my autobiography, hardly less blunt than the more classic status will be beyond contention’. immediate 1927 diary, Prokofiev admits that the dedication of Dreams to Scriabin – clearly Undeniably true, but Prokofiev was destined there in the manuscripts to ‘the composer who to see many important projects fall by the began with Reverie’ – shows more resolve to wayside, productions cancelled – including the follow in the footsteps of his then-idol than original operatic settings of Dostoyevsky’s The the music itself. Indeed, the obsessive opening Gambler and Bryusov’s The Fiery Angel, stalling figurations on muted second violas and violins over which led him to rework the material into bring us closer to a work he mentions in his third symphony – and much else turn to connection with Autumnal, Rachmaninoff’s dust and ashes in the years following his return haunting The Isle of the Dead. -

Prokofiev (1891-1953)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Born in Sontsovka, Yekaterinoslav District, Ukraine. He was a prodigy who played the piano and composed as a child. His formal training began when Sergei Taneyev recommended as his teacher the young composer and pianist Reinhold Glière who spent two summers teaching Prokofiev theory, composition, instrumentation and piano. Then at the St. Petersburg Conservatory he studied theory with Anatol Liadov, orchestration with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and conducting with Nikolai Tcherepnin. He went on to become one of Russia's greatest composer, excelling in practically every genre of music. He left the Soviet Union in 1922, touring as a pianist and composing in Western Europe and America, but returned home permanently in 1936. Symphony No. 1 in D major, Op. 25 "Classical" (1916-7) Claudio Abbado/Chamber Orchestra of Europe ( + Symphony No. 5, Piano Concerto No. 3, Violin Concerto No. 1, Alexander Nevsky, Romeo and Juliet: Suites Nos. and 2 {Excerpts} and Visions Fugitives) DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON PANORAMA 469172-2 (2 CDs) (2000) (original CD release: DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 429396-2 GH) (1990) Claudio Abbado/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 3, Romeo and Juliet - Excerpts, Chout - Excerpts, Hindemith:Symphonic Metamorphoses on Themes by Carl Maria von Weber and Janacek: Sinfonietta) DECCA ELOQUENCE 4806611 (2 CDs) (2012) (original LP release: DECCA SXL 6469/LONDON CS 6679) (1970) Marin Alsop/São Paulo Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 2 and Dreams) NAXOS 8.573353 (2014) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2) SUPRAPHON SU 36702011 (2002) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON DV 5353) (1956) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. -

BENELUX and SWISS SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

BENELUX AND SWISS SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman JEAN ABSIL (1893-1974) BELGIUM Born in Bonsecours, Hainaut. After organ studies in his home town, he attended classes at the Royal Music Conservatory of Brussels where his orchestration and composition teacher was Paul Gilson. He also took some private lessons from Florent Schmitt. In addition to composing, he had a distinguished academic career with posts at the Royal Music Conservatory of Brussels and at the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel and as the long-time director of the Music Academy in Etterbeek that was renamed to honor him. He composed an enormous amount of music that encompasses all genres. His orchestral output is centered on his 5 Symphonies, the unrecorded ones are as follows: No. 1 in D minor, Op. 1 (1920), No. 3, Op. 57 (1943), No. 4, Op. 142 (1969) and No. 5, Op. 148 (1970). Among his other numerous orchestral works are 3 Piano Concertos, 2 Violin Concertos, Viola Concerto. "La mort de Tintagiles" and 7 Rhapsodies. Symphony No. 2, Op. 25 (1936) René Defossez/Belgian National Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 1, Andante and Serenade in 5 Movements) CYPRÈS (MUSIQUE EN WALLONIE) CYP 3602 (1996) (original LP release: DECCA 173.290) (1958) RAFFAELE D'ALESSANDRO (1911-1959) SWITZERLAND Born in St. Gallen. After some early musical training, he studied in Paris under the tutelage of Marcel Dupré (organ), Paul Roës (piano) and Nadia Boulanger (counterpoint). He eventually gave up composing in order to earn a living as an organist. -

Previous Releases in the Roussel Series

KEY RELEASES | January 2012 STÉPHANE DENÈVE CONDUCTS ROUSSEL © J Henry Fair Albert ROUSSEL (1869-1937) Le festin de l’araignée (The Spider’s Banquet) Padmâvatî Ballet Suites Nos 1 and 2 Royal Scottish National Orchestra ∙ Stéphane Denève One of Roussel’s most performed orchestral works, The Spider’s Web was composed during his earlier impressionistic period, and depicts the beauty and violence of insect life in a garden. Roussel’s experiences as a lieutenant in the French Navy first introduced him to Eastern influences, and the ‘operaballet’ Padmâvatî was inspired by his later visit to the ancient city of Chittor in Rajasthan state of western India. It uses aspects of Indian music to evoke this city’s legendary siege by the Mongols. This is the fifth and final volume in Stéphane Denève and the RSNO’s acclaimed survey of Roussel’s orchestral works. “An excellent disc, splendidly and idiomatically performed and a superb advertisement for composer, conductor and orchestra. Highly recommended.” (Gramophone on Vol. 4 / 8.572135) Booklet notes in English Listen to an excerpt from The Spider’s Banquet: Catalogue No: 8.572243 Total Playing Time: 54:53 About Stéphane Denève Stéphane Denève is the newly-appointed Chief Conductor of the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra (SWR) and, since 2005, Music Director of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. He has made regular appearances with the Scottish orchestra at the Edinburgh International Festival and BBC Proms and the Festival Présences, and at celebrated venues throughout Europe including the Vienna Konzerthaus, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, and Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. He and the orchestra have made a number of acclaimed recordings together, including a survey of the works of Albert Roussel for Naxos, the first disc of which won a Diapason d’Or de l’année in 2007. -

Shostakovich Symphony No.4 JAMES EHNES PLAYS KHACHATURIAN

Shostakovich Symphony No.4 JAMES EHNES PLAYS KHACHATURIAN 28 – 31 AUGUST SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY JESSICA ESSIE ANN DOWD SAMUEL BARDEN DAVIS EMMY AWARD WINNER REID SEPTEMBER Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital Mon 2 Sep, 7pm City Recital Hall MOZART ON THE FORTEPIANO MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K570 MOZART Piano Sonata in E flat, K282 MOZART Rondo in A minor, K511 MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K333 Geoffrey Lancaster fortepiano Music from Swan Lake Wed 4 Sep, 7pm Thu 5 Sep, 7pm BEAUTY AND MAGIC Concourse Concert Hall, ROSSINI The Thieving Magpie: Overture Chatswood RAVEL Mother Goose: Suite TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Suite EVERY FAIRY TALE HAS A DARK SIDE Umberto Clerici conductor Star Wars: The Force Awakens Sydney Symphony Presents Thu 12 Sep, 8pm in Concert Fri 13 Sep, 8pm Set 30 years after the defeat of the Empire, Sat 14 Sep, 2pm this instalment of the Star Wars saga sees original Sat 14 Sep, 8pm cast members Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill and Sydney Opera House Harrison Ford reunited on the big-screen, with the Orchestra playing live to film. Classified M. PRESENTATION LICENSED BY PRESENTATION LICENSED BY DISNEY CONCERTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH 20TH CENTURY FOX, LUCASFILM, AND WARNER/CHAPPELL MUSIC. © 2019 & TM LUCASFILM LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © DISNEY A NEW FOXTEL ORIGINAL Andreas Brantelid performs Meet the Music Elgar’s Cello Concerto Wed 18 Sep, 6.30pm Thursday Afternoon Symphony VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY’S MASTERWORKS Thu 19 Sep, 1.30pm VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Tea & Symphony* WATCH FROM JULY 21 Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis Fri 20 Sep, -

Digital Program KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN COMPETITION for KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION YOUNG PIANISTS 2020

chopincompetitiondc.org Digital Program KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN COMPETITION FOR KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION YOUNG PIANISTS 2020 KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION With great excitement and pride I welcome you to the 2020 Kosciuszko Foundation Online Chopin Piano Competition for Young Pianists. Two years ago, in 2018, we hosted the inaugural competition in Washington D.C., and last year, in 2019, we organized the Chopin Piano Academy, an intensive weekend of master classes. Both events were a great success and a truly wonderful experience for all involved. The year 2020 has brought changes and challenges, and we are not able to host the 2020 competition in person. Barbara Bernhardt, Director Instead, we invite you to join us virtually. Please tune in to witness this remarkable musical happening, where we will Kosciuszko Foundation have a chance to see and hear 33 young and talented Washington D.C. pianists from all around the world. I wish to all our contestants good luck and to all of you a wonderful weekend with the music of Chopin! CHOPIN COMPETITION D.C. It is my pleasure and great honor to welcome you to the 2nd edition of the Kosciuszko Foundation Chopin Competition for Young Pianists. This year has brought an unexpected change in our lives, which resulted in the cancelation of the majority of musical events around the world. However, as a wise person once said “If you will it, it is no Dream." We at the Kosciuszko Foundation always strive to achieve our dreams and this online competition is the sole proof of that. Our never-ending goal is to continue to foster the legacy of Poland’s greatest composer among the youngest generation of pianists.