Dictionary of Music.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Ed Roche Audiovisual Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

Title of Collection: Ed Roche Audio Collection Reference Code: US-MoKcUMS-MSAM0005 Repository: Marr Sound Archives UMKC Miller Nichols Library 800 E. 51st Street Kansas City, MO 64110 Creator: Roche, Ed Biographical History: From 1935 until his retirement in 1991, Ed Roche recorded the sounds of Kansas City. The first engineer for Kansas City’s Municipal Auditorium, Roche installed and operated the then state of-the-art audio system. He meticulously documented music and civic events, including performances of the Kansas City Philharmonic. In 1952, Roche established Crown Recording Studio. Crown quickly became one of Kansas City’s leading studios. Over the years, Roche recorded thousands of bands, choruses and radio programs including the Kansas City Hour. Roche produced tapes for the Nazarene Church that were distributed internationally. During the 1980s, he preserved the open-reel tapes and instantaneous cut discs for the Harry Truman Presidential Library. Date Range: 1935-1967 Extent: 7 linear feet, includes 629 grooved discs and 15 open reel tapes. Scope and Content: The Ed Roche Audio Collection contains many unique items recorded in the Kansas City area, including political speeches, musical performances, religious services, and advertisements for businesses and organizations. The Kansas City Philharmonic Orchestra and the Kansas City Conservatory of Music are strongly represented with numerous recordings of each entity. Finally, the collection also holds some national radio programs, such as “The Guiding Light,” “Hymns of All Churches,” and “Michael Shayne.” University of Missouri – Kansas City Marr Sound Archives Conditions of Access: The collection is open for research and educational use. The physical items in this collection are non- circulating. -

The Shaping of Time in Kaija Saariaho's Emilie

THE SHAPING OF TIME IN KAIJA SAARIAHO’S ÉMILIE: A PERFORMER’S PERSPECTIVE Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS May 2020 Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Brent E. Archer Graduate Faculty Representative Elaine J. Colprit Nora Engebretsen-Broman © 2020 Maria Mercedes Diaz Garcia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor This document examines the ways in which Kaija Saariaho uses texture and timbre to shape time in her 2008 opera, Émilie. Building on ideas about musical time as described by Jonathan Kramer in his book The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies (1988), such as moment time, linear time, and multiply-directed time, I identify and explain how Saariaho creates linearity and non-linearity in Émilie and address issues about timbral tension/release that are used both structurally and ornamentally. I present a conceptual framework reflecting on my performance choices that can be applied in a general approach to non-tonal music performance. This paper intends to be an aid for performers, in particular conductors, when approaching contemporary compositions where composers use the polarity between tension and release to create the perception of goal-oriented flow in the music. iv To Adeli Sarasola and Denise Zephier, with gratitude. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the many individuals who supported me during my years at BGSU. First, thanks to Dr. Emily Freeman Brown for offering me so many invaluable opportunities to grow musically and for her detailed corrections of this dissertation. -

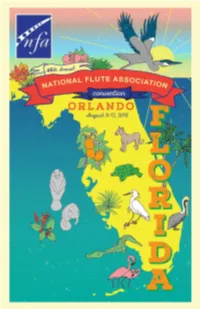

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

The Vox Continental

Review: The Vox Continental ANDY BURTON · FEB 12, 2018 Reimagining a Sixties Icon The original Vox Continental, rst introduced by British manufacturer Jennings Musical Industries in 1962, is a classic “combo organ”. This sleek, transistor-based portable electric organ is deeply rooted in pop-music history, used by many of the biggest rock bands of the ’60’s and beyond. Two of the most prominent artists of the era to use a Continental as a main feature of their sound were the Doors (for example, on their classic 1967 breakthrough hit “Light My Fire”) and the Animals (“House Of The Rising Sun”). John Lennon famously played one live with the Beatles at the biggest-ever rock show to date, at New York’s Shea Stadium in 1965. The Continental was bright orange-red with reverse-color keys, which made it stand out visually, especially on television (which had recently transitioned from black-and-white to color). The sleek design, as much as the sound, made it the most popular combo organ of its time, rivaled only by the Farsa Compact series. The sound, generated by 12 transistor-based oscillators with octave-divider circuits, was thin and bright - piercing even. And decidedly low-delity and egalitarian. The classier, more lush-sounding and expensive Hammond B-3 / Leslie speaker combination eectively required a road crew to move around, ensuring that only acts with a big touring budget could aord to carry one. By contrast, the Continental and its combo- organ rivals were something any keyboard player in any band, famous or not, could use onstage. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

Revue Catalane Pierre Talrich

8' AMCC. H' 86 Février 1914. -es MïntBcrKS non ti»cTci ne sont oas rtnau.. REVUE Arttcio parus oan» u Revue n cn^igcni auc icurs auteur*. CATALANE PIERRE TALRICH Jean-Pierre-François Talrich naquit à Serralongue (Pyr.- Or.) le 16 janvier 1810. Fils de Pierre Talrich, docteur en chirurgie, et de Thérèse Durand, il fut baptisé le 22 janvier en l'église de Serralongue et eut comme marraine Marie- Rose Trescases. Le 20 mars 1813. l'enfant perdait sa mère alors qu'il était déjà orphelin de père. Le docteur Talrich, lors d'une épi• démie de typhus, descendit de Serralongue pour aider ses confrères de Céret, fut atteint par le fléau et mourut victime de son devoir. L'orphelin fut mis au collège de Perpignan, mais le petit montagnard, ignorant de ce qu'il pourrait trouver dans la grand'ville inconnue, prit soin, en partant, d'emporter son livre d'école sous son bras. Au lycée, un épisode de son enfance révèle déjà sa naturelle générosité d'âme et son enthousiasme pour les nobles causes. En 1824, âgé de quatorze ans, il s'évada avec quelques camarades ayant formé le projet très simple de partir au secours des Grecs. Malheureusement, l'un de ces jeunes émules de Lord Byron avait eu une préoccupation vraiment trop bourgeoise et qui devait lui être fatale : il avait laissé sous son oreiller son testament olographe par lequel il - 34 - déshéritait, en bonne et due forme, son neveu qui lui avait, quelques jours auparavant, administré une très irrespec• tueuse raclée. Ce document faisait connaître les intentions des futurs guerriers. -

BH Program FINAL

MUSIC BEFORE 1800 Louise Basbas, Director Blue Heron Christmas at the Courts of 15th-Century France & Burgundy Scott Metcalfe, director and harp Jennifer Ashe, Pamela Dellal, Martin Near, Daniela Tosic Michael Barrett, Owen McIntosh, Jason McStoots, Stefan Reed, Mark Sprinkle, Sumner Tompson Cameron Beauchamp, Paul Guttry Laura Jeppesen, vielle and rebec; Charles Weaver, lute and voice Advent O clavis David (O-antiphon for December 20) plainchant Factor orbis Jacob Obrecht (1457/8 - 1505) O virgo virginum (O-antiphon for December 24) plainchant O virgo virginum Josquin Desprez (c. 1455 - 1521) Conditor alme siderum (alternatim hymn for Advent) Guillaume Du Fay (c. 1397 - 1474) Ave Maria gratia dei plena Antoine Brumel (c. 1460 - c. 1512) Christmas O admirabile commercium / Verbum caro factum est Johannes Regis (c. 1425 - 1426) INTERMISSION Christmas Letabundus (Christmas sequence) Guillaume Du Fay Praeter rerum seriem Adrian Willaert (c. 1490 - 1562 New Year’s Day La plus belle et doulce figure Nicolas Grenon (c. 1380 - 1456) Dieu vous doinst bon jour et demy Guillaume Malbecque (c. 1400 - 1465) Dame excellent ou sont bonté, scavoir Baude Cordier (d. 1397/8?) De tous biens playne (instrumental) Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435 - 1511?) Margarite, fleur de valeur Gilles Binchois (c. 1400 - 1460) Ce jour de l’an voudray joie mener Guillaume Du Fay Christmas Gloria Spiritus et alme Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370 - 1412) Nato canunt omnia Antoine Brumel Tis concert is sponsored, in part, by the Florence Gould Foundation, Music Before 1800’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.