Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-Brass-Audition-Packet.Pdf

Dear Brass Line Candidate, Thank you for your interest in the 7th Regiment Drum and Bugle Corps! This packet will serve as your primary resource for video auditions. Read everything in this booklet carefully and prepare all of the required materials to the best of your ability. VISUAL AUDITION MATERIALS Basics of Marching Technique: Our technique program is “straight leg” marching; that is, we strive for the longest line between our hip and ankle bone at all times. Allowing the leg to bend at the knee shortens that line. The following are basic definitions for those who are unfamiliar with our technique. ● We stand in first position. With your heels together you will turn your feet outward 45 degrees. This turnout will come from the hips. Make sure your knees are in line with your middle toe. ● Horn Carriage: When at playing position (or carry) create a wide triangle with your forearms and horn. ● Forward March: articulate each beat with the back of your heel as you move forward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Backwards March: articulate each beat with the platform of your foot keeping your heel low to the ground as you move backward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Crossing Counts: The point at which your ankle bones are right next to each other while marching. This should happen on the ‘& count’ when marching in a duple (4/4) meter. ● 5 Points of Alignment: generate uniform posture by keeping your ears (1), shoulders (2), hips (3), and knees (4) stacked vertically from your ankle bones (5). -

Aubrey Brain (1893-1955)

Aubrey Brain (1893-1955) Aubrey Harold Brain was the son of A.E. Brain, Senior, brother of Alfred Brain, Junior, and father of Dennis Brain – all distinguished horn players. Another brother, Arthur, also played horn, but abandoned music to become a police officer. Aubrey’s first instrument was the violin, but he soon switched to horn. He first studied with his father, then with Adela Sutcliffe and Eugene Mieir, and finally with Friedrich Adolph Borsdorf at the Royal College of Music in 1911. He played in the North London Orchestral Society during his College years and was appointed principal horn of the New Symphony Orchestra in 1911. He went on the London Symphony Orchestra's tour of the US under Arthur Nikish in 1912; his father was unable to go on the tour because of his contract with Covent Garden. After returning from the tour, Aubrey joined his father and brother in a memorial concert for the Titanic. Aubrey became principal horn of Sir Thomas Beecham's opera company orchestra in 1913. It was during a tour with this company that he met Marion Beeley, a contralto for whom Sir Edward Elgar wrote "Hail, Immortal Ind!" in his opera The Crown of India. They were married in 1914. Aubrey’s early career was shadowed by the success of his older brother, Alfred, who dominated the scene until he left for the United States in 1922, and of his teacher, Borsdorf, until Borsdorf was forced to resign because of anti-German feeling at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. -

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

(ABH) and Gesellschaft Für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany

Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. The narrative contrasts the strategies followed by two brass instrument manufacturers, one a new entrant the other an incumbent. It shows how the new entrant despite a slow start, small scale and a commitment to traditional artisanal skills, was able to develop the technology of the German horn and establish itself as one of the world’s leading brands of horn, while the incumbent firm despite being the first to innovate steadily lost ground until like many of the other leading horn makers of the 1930s, it eventually exited the industry. Keywords: Disruptive innovation, Creative Industries, Musical Instruments Introduction For much of the 19th and a substantial part of the 20th century, British orchestras had a distinctive sound. This differentiated them from their counterparts in many parts of Europe and the United States. This sound was the product of the instruments they played, most notably in the horn section of the orchestra. In Britain horn players typically utilized instruments modelled on the Raoux horn from France. -

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Care & Maintenance

Care and Maintenance of the Euphonium and Piston-Valve Tuba You Will Need: 1) Soft cloth (cotton or flannel) 4) Valve brush 2) Flexible brush (also called a “snake”) 5) Tuning slide grease 3) Mouthpiece brush 6) Valve Oil Daily Care 1) Never leave your instrument unattended. It takes very little time for someone to take it. 2) The safest place for your instrument is in the case. Leave it there when you’re not playing. 3) Do not let other people use your instrument. They may not know how to hold and care for it. 4) Do not use your case as a chair, foot rest or step stool. It is not designed for that kind of weight. 5) Lay your case flat on the floor before opening it. Do not let it fall open. 6) Do not hit your mouthpiece, it can get stuck. 7) Do not lift your instrument by the valves. Use the bell and any large tubes on the outside edge. 8) No loose items in your case. Anything loose will damage your instrument or get stuck in it. 9) Do not put music in your case, unless space is provided for it. If you have to fold it or if it touches the instrument, it should NOT be there. 10) Avoid eating or drinking just before playing. If you do, rinse your mouth with water before playing. 11) You may not need to do it every day, but keep your valves running smooth with valve oil. Put the oil directly on the exposed valve, not in the holes on the bottom of the casings. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

BWTB Revolver @ 50 2016

1 PLAYLIST AUG. 7th 2016 Part 1 of our Revolver @ 50 Special~ We will dedicate to early versions of songs…plus the single that preceded the release of REVOLVER…Lets start with the first song recorded for the album it was called Mark 1 in April of 1966…good morning hipsters 2 9AM The Beatles - Tomorrow Never Knows – Revolver TK1 (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: John The first song recorded for what would become the “Revolver” album. John’s composition was unlike anything The Beatles or anyone else had ever recorded. Lennon’s vocal is buried under a wall of sound -- an assemblage of repeating tape loops and sound effects – placed on top of a dense one chord song with basic melody driven by Ringo's thunderous drum pattern. The lyrics were largely taken from “The Psychedelic Experience,” a 1964 book written by Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, which contained an adaptation of the ancient “Tibetan Book of the Dead.” Each Beatle worked at home on creating strange sounds to add to the mix. Then they were added at different speeds sometime backwards. Paul got “arranging” credit. He had discovered that by removing the erase head on his Grundig reel-to-reel tape machine, he could saturate a recording with sound. A bit of….The Beatles - For No One - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: Paul 3 The Beatles - Here, There And Everywhere / TK’s 7 & 13 - Revolver (Lennon-McCartney) Lead vocal: Paul Written by Paul while sitting by the pool of John’s estate, this classic ballad was inspired by The Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.” Completed in 14 takes spread over three sessions on June 14, 16 and 17, 1966. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

Califcrnia Institute Of

FEBRUARY, 1959 50e CALIFCRNIA INSTITUTE OF F E tri 1 0 1959 TECHNO! OGY 1 ENGINFF-ntA,.. LIBRARY www.americanradiohistory.com basic contributions to our culture Invention of the screw propeller in 1836 by John Ericsson provided water transportation with a means for using steam power that was far superior to any method of propulsion previously devised. In our day radial refraction, brought to you by the laboratories of James B. Lansing Sound, Inc., provides the best-and perhaps the ultimate-method of reproducing two channel stereophonic music in your home. Radial refraction integrates two, balanced 1BL precision loudspeaker systems to eliminate the "hole in the middle," obviate "split" soloists, and to distribute the stereo effect over a wide area. The two, full -range, balanced speaker systems used reproduce all of the phenomena required for full stereo perception. Radial refraction was first used in the JBL Ranger -Paragon, a magnificent instrument that has found its way into the great homes of audio cognoscente throughout the world. Now a smaller unit, the JBL Ranger-Metregon, has been designed to bring radially refracted stereo to the usual -sized living room. No less than seven different JBL speaker systems may be used with the Metregon. You may wish to make use of JBL transducers you,now own for one channel, and install matching units in the other. You may progressively upgrade your Metregon system. Write for a complete description of the JBL Ranger-Metregon and the name and address of the Authorized JBL Signature Audio Specialist in your community. i!! JAMES B. LANSING SOUND, INC., 3249 Casitas Ave., Los Angeles 39, Calif. -

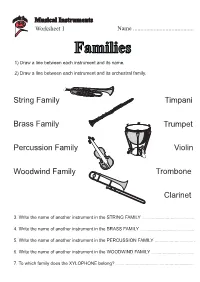

Families 2) Draw a Line Between Each Instrument and Its Orchestral Family

Musical Instruments Worksheet 1 Name ......................................... 1) Draw a line between each instrument and its name.Families 2) Draw a line between each instrument and its orchestral family. String Family Timpani Brass Family Trumpet Percussion Family Violin Woodwind Family Trombone Clarinet 3. Write the name of another instrument in the STRING FAMILY .......................................... 4. Write the name of another instrument in the BRASS FAMILY ........................................... 5. Write the name of another instrument in the PERCUSSION FAMILY ................................ 6. Write the name of another instrument in the WOODWIND FAMILY .................................. 7. To which family does the XYLOPHONE belong? ............................................................... Musical Instruments Worksheet 3 Name ......................................... Multiple Choice (Tick the correct family) String String String Oboe Brass Double Brass Bass Brass Woodwind bass Woodwind drum Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cymbals Brass Bassoon Brass Trumpet Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String French Brass Cello Brass Clarinet Brass horn Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cor Brass Trombone Brass Saxophone Brass Anglais Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Viola Brass Castanets Brass Euphonium Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion