A Brief History of Piston-Valved Cornets'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-Brass-Audition-Packet.Pdf

Dear Brass Line Candidate, Thank you for your interest in the 7th Regiment Drum and Bugle Corps! This packet will serve as your primary resource for video auditions. Read everything in this booklet carefully and prepare all of the required materials to the best of your ability. VISUAL AUDITION MATERIALS Basics of Marching Technique: Our technique program is “straight leg” marching; that is, we strive for the longest line between our hip and ankle bone at all times. Allowing the leg to bend at the knee shortens that line. The following are basic definitions for those who are unfamiliar with our technique. ● We stand in first position. With your heels together you will turn your feet outward 45 degrees. This turnout will come from the hips. Make sure your knees are in line with your middle toe. ● Horn Carriage: When at playing position (or carry) create a wide triangle with your forearms and horn. ● Forward March: articulate each beat with the back of your heel as you move forward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Backwards March: articulate each beat with the platform of your foot keeping your heel low to the ground as you move backward and generate the longest possible leg line on the crossing counts. ● Crossing Counts: The point at which your ankle bones are right next to each other while marching. This should happen on the ‘& count’ when marching in a duple (4/4) meter. ● 5 Points of Alignment: generate uniform posture by keeping your ears (1), shoulders (2), hips (3), and knees (4) stacked vertically from your ankle bones (5). -

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Funderburk, Jeff, "The Man and His Horn", T.U.B.A. JOURNAL May, 1988 P 43

Funderburk, Jeff, "The Man and his Horn", T.U.B.A. JOURNAL May, 1988 p 43 This fabulous tuba was reportedly designed by Bill Johnson, design engineer for the J.W. York Band Instrument Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan. According to the story, Leopold Stokowski, conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in the 1930s, approached the orchestra's tubist, Phillip Donatelli, and requested that he obtain a tuba that would provide a true organ like quality to the bass register of the orchestra. Mr. Donatelli consulted with the York Instrument Company, a firm noted for excellent tubas. Two instruments pitched in CC were built to order. These incorporated a medium-large piston valve section (larger than any built today!) and a large bore rotary fifth valve into the body of a Kaiser tuba with a 20-inch bell diameter. As fate would have it, Mr. Donatelli did not feel comfortable with these instruments. One reason for this was the very short leadpipe used on the instruments. Mr. Donatelli was overweight to the point that when he breathed, the instrument was forced away from him. There was no room on the chair for the two of them! Consequently, the instruments were sold. One instrument was sold to Arnold Jacobs, a student at Curtis Institute, for the price of $175, to be paid off at a rate of $5 per week. Mr. Jacobs and his tuba were so well liked by the orchestra director at the Curtis Institute - Fritz Reiner - that a limousine was sent on rehearsal days to collect the two of them from home. -

Band Director's Catalog

BAND DIRECTor’s CATALOG We make legends. A division of Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 www.conn-selmer.com AV4230 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eb Soprano, Harmony & Eb Alto Clarinets ....... 10 Bb Bass, EEb Bass & BBb Bass Clarinets ........... 11 308 Student Instruments Step-Up & Pro Saxophones .............................. 12-13 Step-Up & Pro Bb Trumpets .............................. 14 Piccolos & Flutes ...................................................... 1 Step-Up & Pro Cornets ..................................... 14 Oboes & Clarinets .................................................... 2 C Trumpets, Harmony Trumpets, Flugelhorns .... 15 Saxophones .............................................................. 3 Step-Up & Pro Trombones ................................ 16-17 204 Trumpets & Cornets .................................................. 4 Alto, Valve & Bass Trombones .......................... 18 Trombones ............................................................... 5 Double Horns .................................................. 19 PICCOLOS Single Horns ............................................................ 5 Baritones & Euphoniums .................................. 20 Educational Drum, Bell and Combo Kits .................. 6 BBb Tubas - Three Valve .................................... 21 ARMSTRONG Mallet Instruments .................................................... 6 BBb & CC Tubas - Four Valve ............................ 21 204 “USA” – Silver-plated headjoint and body, silver-plated -

Page 14 Street, Hudson, 715-386-8409 (3/16W)

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 1 10/14/10 7:08 PM ANNOUNCING A NEW DVD TEACHING TOOL Do you sit at a theatre organ confused by the stoprail? Do you know it’s better to leave the 8' Tibia OUT of the left hand? Stumped by how to add more to your intros and endings? John Ferguson and Friends The Art of Playing Theatre Organ Learn about arranging, registration, intros and endings. From the simple basics all the way to the Circle of 5ths. Artist instructors — Allen Organ artists Jonas Nordwall, Lyn Order now and recieve Larsen, Jelani Eddington and special guest Simon Gledhill. a special bonus DVD! Allen artist Walt Strony will produce a special DVD lesson based on YOUR questions and topics! (Strony DVD ships separately in 2011.) Jonas Nordwall Lyn Larsen Jelani Eddington Simon Gledhill Recorded at Octave Hall at the Allen Organ headquarters in Macungie, Pennsylvania on the 4-manual STR-4 theatre organ and the 3-manual LL324Q theatre organ. More than 5-1/2 hours of valuable information — a value of over $300. These are lessons you can play over and over again to enhance your ability to play the theatre organ. It’s just like having these five great artists teaching right in your living room! Four-DVD package plus a bonus DVD from five of the world’s greatest players! Yours for just $149 plus $7 shipping. Order now using the insert or Marketplace order form in this issue. Order by December 7th to receive in time for Christmas! ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 2 10/14/10 7:08 PM THEATRE ORGAN NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 Volume 52 | Number 6 Macy’s Grand Court organ FEATURES DEPARTMENTS My First Convention: 4 Vox Humana Trevor Dodd 12 4 Ciphers Amateur Theatre 13 Organist Winner 5 President’s Message ATOS Summer 6 Directors’ Corner Youth Camp 14 7 Vox Pops London’s Musical 8 News & Notes Museum On the Cover: The former Lowell 20 Ayars Wurlitzer, now in Greek Hall, 10 Professional Perspectives Macy’s Center City, Philadelphia. -

The Improvements of Brass Instruments from 1800 to 1850 Including Implications for Their Usage

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1965 The mprI ovements of Brass Instruments from 1800 to 1850 Including Implications for Their sU age Delmar T. Vollrath Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Music at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Vollrath, Delmar T., "The mprI ovements of Brass Instruments from 1800 to 1850 Including Implications for Their sU age" (1965). Masters Theses. 4300. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4300 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Improvements of Brass Instruments from - 1800 to 1850 Including Implications for Their Usage (TITLE) BY Delmar To Vollrath THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in Education IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS --.12�65�- YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE DATE JI, !f{j_ ol\ln TA.llLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I Introduction • • • • • , •• • • • • • • l JI �t ................ 4 III Cornet • • • • • • • • • , • • • • • • IV Tronlhone • • • • • • • .. • , • • •. • • • 18 v Horn • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••• 22 VI • • • • • • • 4i •••• " • • -'II' •• JJ VII • • • • • • • . ' . .. 39 VIll BU'itone and EuphoniU111 • II •• e II e •• 43 IX Saxophone ••••• • ..... • • • • • I Conolu•ion • • • • • • • .• • • " .... r-''} . • .. APi'ii2IDTX , "' • . • • . ... ,.. BI BL!OORAP!II • • • • • • • • • • . .. The ;:mrpose o:': this stud,)' is to axwni.ne one ;:;'.:&oo of tho evolution of 111J.ls1.oal :tnstrunentsJ that oi' t',e p'1�,;ica1 isi:pr'.ive":ents of brass wind instruments !'roui 1800 to 1 ,50, i:::i the '1opc that a more hharough understanding of the :instru- 1..:ints and their back1;ro·.md will re ;:tlt. -

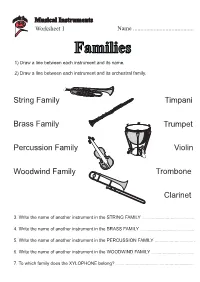

Families 2) Draw a Line Between Each Instrument and Its Orchestral Family

Musical Instruments Worksheet 1 Name ......................................... 1) Draw a line between each instrument and its name.Families 2) Draw a line between each instrument and its orchestral family. String Family Timpani Brass Family Trumpet Percussion Family Violin Woodwind Family Trombone Clarinet 3. Write the name of another instrument in the STRING FAMILY .......................................... 4. Write the name of another instrument in the BRASS FAMILY ........................................... 5. Write the name of another instrument in the PERCUSSION FAMILY ................................ 6. Write the name of another instrument in the WOODWIND FAMILY .................................. 7. To which family does the XYLOPHONE belong? ............................................................... Musical Instruments Worksheet 3 Name ......................................... Multiple Choice (Tick the correct family) String String String Oboe Brass Double Brass Bass Brass Woodwind bass Woodwind drum Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cymbals Brass Bassoon Brass Trumpet Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String French Brass Cello Brass Clarinet Brass horn Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cor Brass Trombone Brass Saxophone Brass Anglais Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Viola Brass Castanets Brass Euphonium Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion -

Tutti Brassi

Tutti Brassi A brief description of different ways of sounding brass instruments Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2018 The author’s moral rights have been asserted Hataf Segol Publications 2018 Typeset in XƎLATEX by Simon Montagu Why Mouthpieces 1 Cornets and Bugles 16 Long Trumpets 19 Playing the Handhorn in the French Tradition 26 The Mysteries of Fingerhole Horns 29 Horn Chords and Other Tricks 34 Throat or Overtone Singing 38 iii This began as a dinner conversation with Mark Smith of the Ori- ental Institute here, in connexion with the Tutankhamun trum- pets, and progressed from why these did not have mouthpieces to ‘When were mouthpieces introduced?’, to which, on reflection, the only answer seemed to be ‘Often’, for from the Danish lurs onwards, some trumpets or horns had them and some did not, in so many cultures. But indeed, ‘Why mouthpieces?’ There seem to be two main answers: one to enable the lips to access a tube too narrow for the lips to access unaided, and the other depends on what the trumpeter’s expectations are for the instrument to achieve. In our own culture, from the late Renaissance and Early Baroque onwards, trumpeters expected a great deal, as we can see in Bendinelli’s and Fantini’s tutors, both of which are avail- able in facsimile, and in the concert repertoire from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo onwards. As a result, mouthpieces were already large, both wide enough and deep enough to allow the player to bend the 11th and 13th partials and other notes easily. The transition from the base of the cup into the backbore was a sharp edge. -

So You Want to Buy a Horn

So, You Want to Buy A Horn! Recommended brands: DOMESTIC Holton (Farkas 179, 180; H-188, H-105, H-190, H-191, Merker 175) Conn (8D, 8DY, 8DR, 10D, 10DR, 11D, and 11DR) King (Eroica) Yamaha (667, 667V, 668, 668V) FOREIGN Hoyer (6801 –Kruspe wrap; 6801K-Geyer wrap) Alexander (103, 200) Paxman (25, 23; the most popular bell sizes are L or A) Finke PRESTIGE HORNS Englebert Schmid Lawson Lewis Geyer Lechniuk Hill Rausch Berg McCraken Patterson Atkinson Kuehn OK, WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THESE INSTRUMENTS? It really all depends on what you are looking for. Domestic instruments, as well as some foreign instruments, are massed produced. This means that during a manufacturing ‘run,’ many instruments are coming off the assembly line in close succession. With regard to domestic makers, this is even more so as demand for instruments is greater than supply so there may be a waiting period for delivery of instruments. Thus, the manufacturer is concerned with meeting up with the supply. This means that there is not enough time to detail out the instrument, making sure that slides and valves are fitted properly or are in good alignment. When buying a new massed produced instrument, often the instrument will need a professional preparation, to bring it up to normal standards. It is an unfortunate circumstance, but often this is a common fact nowadays. Some mass produced instruments, such as the Conn 8D, have had a storied history. At certain times during their manufacture, these instruments were of superior quality and have many desired response traits. -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

Trumpet, Cornet, Flugelhorn GRADE 6 from 2017

Trumpet, Cornet, Flugelhorn GRADE 6 from 2017 PREREQUISITE FOR ENTRY: ABRSM Grade 5 (or above) in Music Theory, Practical Musicianship or any solo Jazz subject. For alternatives, see www.abrsm.org/prerequisite. THREE PIECES: one chosen by the candidate from each of the three Lists, A, B and C: LIST A 1 Albrechtsberger Larghetto: 3rd movt from Concertino (Brass Wind) 2 J. S. Bach Esurientes implevit bonis (from Magnificat). Baroque Around the Clock for Trumpet, arr. Blackadder and Gout (Brass Wind) 3 Fiala Largo (observing cadenza): 1st movt from Divertimento in D (Faber) 4 Gibbons The King’s Juell. No. 4 from Gibbons Keyboard Suite for Trumpet, arr. Cruft (Stainer & Bell 2588: B b/C edition) 5 Handel Allegro: 2nd movt from Sonata (in A b), Op. 1 No. 11. No. 2 from Handel Two Sonatas, trans. Varasdy and Orbán (Editio Musica Budapest Z.13933) 6 Haydn Andante: 2nd movt from Trumpet Concerto in E b, Hob. VIIe/1 (Henle HN 456 or Universal HM 223: B b/E b edition) 7 Mendelssohn Allegretto grazioso only. Mendelssohn Songs without Words Nos 9 and 30, arr. Round (Wright & Round ) 8 Mozart Alleluia (from Exultate Jubilate). Trumpet in Church, arr. Denwood (Emerson E283) 9 Stanley Trumpet Voluntary, Op. 6 No. 5. No. 11 from Old English Trumpet Tunes, Book 1, arr. Lawton (OUP ) LIST B 1 Leroy Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby (Alfred 41061) 2 Gershwin Theme (from Rhapsody in Blue). Concert Repertoire for Trumpet, arr. Calland (Faber) 3 Hubeau Sarabande: 1st movt from Sonata for Trumpet (Durand: B b/C edition) 4 Bryan Kelly Colonel Glib (Retired) or The Chase: No.