Boosey & Hawkes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Paris // December 8, 2016

PRESS RELEASE PARIS // DECEMBER 8, 2016 The 15th edition of the Private Equity Exchange & Awards was held in Paris on December 8, 2016. 1,200 participants – Limited Partners, Private Equity Funds and Corporate Executives – gathered for this major Pan-European summit on private equity and restructuring followed by a high-class evening ceremony rewarding the best performers among LBO Funds, Limited Partners and Management Teams. AN INTENSIVE ONE-DAY PROGRAM… 80 outstanding speakers from all over Europe shared their expertise through interactive round-tables and keynote speeches in three main tracks: International LBO & Fundraising; LBO & Management; Underperformance, Restructuring & Private Equity. Experts included: Pascal Blanqué, Chief Investment Officer, Amundi Blair Jacobson, Partner, Ares Management Mark Ligertwood, Partner, Dunedin Fabrice Nottin, Partner, Apollo Global Management Jean-Baptiste Wautier, Managing Partner, BC Partners, etc... DOWNLOAD THE SPEAKERS’ LINE UP …FOCUSING ON NETWORKING OPPORTUNITIES The Private Equity Exchange & Awards promoted targeted networking opportunities in several ways. The Business lunch allowed participants to develop their network and meet participants with diverse profiles. Thanks to the exclusive One-to-One Meetings, participants benefited from a targeted networking planning their meetings ahead of the event through a dedicated online platform. …CONCLUDED BY A PRESTIGIOUS GALA EVENING The gala dinner followed by the Awards Ceremony was the crowning achievement of the event, rewarding the best Private Equity players – LBO, Venture and Growth Capital Funds, Limited Partners and Management Teams – on the long run. Over 80 jury members, top Limited Partners and Asset Management professionals, committed themselves to assess the application forms submitted by carefully preselected nominees. Laureates were rewarded on stage in front of more than 450 private equity players. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Value in Private Equity: Where Social Meets Shareholder 3 OPPORTUNITIES ALIGNED

VALUE IN PRIVATE EQUITY WHERE SOCIAL MEETS SHAREHOLDER By Mark Hepworth Big Issue Invest March 2014 2 MOVING TOWARDS AN ERA OF OPPORTUNITY FOR ALL... The imbalance of opportunity in society is as striking today as it ever was. In my opinion though, this lack of opportunity is caused, not so much by opportunity not being there, but because of the lack of educational qualifications, or other criteria, such as direction and focus being absent in poorer sections of society. Clearly someone who attended private school, comes from a wealthy and educated family, and who completed their education to degree level is more likely to achieve than someone who was brought up as part of a one parent family, located in an inner city borough, didn’t attend much school and left at the earliest opportunity without any exam passes. Opportunity is always there for those naturally gifted, or lucky enough to spot it, or perhaps those educated enough to recognise it. I recently had lunch with a leading politician and mentioned my belief that we simply must find a way of linking the powerful stallions of free enterprise to the carriage of humanity that follows behind. It is essential in a modern democratic society that we work toward inclusion for all. Forget making the rich poorer, let’s make the poor richer. To most, the goal of private equity investment is typically seen as working in direct conflict to this goal of social inclusion. The media tends to distort and exaggerate the sector like a pantomime villain - asset stripping, job losses, financial engineering...the list goes on. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

Foreign Books in Romantic-Period London Diego Saglia

51 The International “Commerce of Genius”: Foreign Books in Romantic-Period London Diego Saglia This essay addresses the question of the presence and availability of foreign books in London between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. After considering the difficulties related to obtaining foreign volumes from pri - vate libraries, such as that of Holland House, it turns to examine the role played by periodicals in reviewing foreign titles and advertising the lists and catalogues of those booksellers who stocked and sold foreign works. Focusing on some of the most successful among them (such as Boosey, Treuttel and Würtz, Deboffe and Dulau), the essay sketches out a map of their businesses in London, the languages they covered, their different groups of customers, as well as the commercial and political risks to which they were exposed. As this preliminary investigation makes clear, this mul - tifaceted phenomenon has not yet been the object of detailed explorations and reconstructions. Accordingly, this essay traces the outline of, and ad - vocates, a comprehensive study of the history of the trade in foreign pub - lications in London and Britain at the turn of the nineteenth century. By filling a major gap in our knowledge of the history of the book, this recon - struction may also offer invaluable new insights into the international co- ordinates of the literary field in the Romantic era, and particularly in the years after Waterloo, when the cross-currents of an international “com - merce of genius” (as the Literary Gazette called it in 1817) became an in - trinsic feature of an increasingly cosmopolitan cultural milieu. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Cameron Burgess - Clarinet BBM Youth Support Report - June 2013

Cameron Burgess - Clarinet BBM Youth Support Report - June 2013 My trip to the UK was an incredibly rewarding and exciting experience. In my lessons I gained a wealth of information and ideas on how to perform British clarinet repertoire, and many different approaches and concepts to improve my technique, which I have found invaluable in my development as a musician. I was also able to collect a vast amount of data on Frederick Thurston, who is the focal point of my honours thesis. Much of this information I probably would not have discovered had it not been for my trip to the UK. I was also fortunate enough to attend numerous concerts by the London Symphony Orchestra, Halle Orchestra, London Chamber Orchestra and Southbank Sinfonia, as well as visit London’s many galleries and museums. After arriving in the UK I traveled from Manchester to London for my first lesson, which was with the Principal of the Royal College of Music and renowned Mozart scholar, Professor Colin Lawson. Much of my time in this lesson was devoted to Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto. I had been fortunate enough to attend a master class given by Professor Lawson at the Sydney Conservatorium in 2010 and had gained some ideas on how to interpret the work, however this was expanded on greatly, and my ideas and concepts on how to perform the work completely changed. As well as this we spent some time discussing my thesis topic, how it could potentially be improved and what new ideas I could also include. Professor Lawson also very generously provided me with some incredibly useful literature on Thurston, published for his centenary celebration, which is no longer in print. -

Boosey & Hawkes and Clarinet Manufacturing in Britain, 1879-1986

From Design to Decline: Boosey & Hawkes and Clarinet Manufacturing in Britain, 1879-1986 Jennifer May Brand Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Goldsmiths, University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2012 Volume 1 of 2 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented here is my own. Jennifer May Brand November 2012 2 Acknowledgements My thanks are extended to the following people and organisations, who have made the creation of this thesis possible: • The AHRC, for funding the initial period of research. • My supervisors, Professor Stephen Cottrell and Doctor Bradley Strauchen- Scherer, for their wisdom and guidance throughout the process. • All the staff at the Horniman Museum, especially those in the Library, Archives and Study Collection Centre. • Staff and students at Goldsmiths University, who have been a source of support in various ways over the last few years. • All the organologists and clarinettists who have permitted me to examine their instruments, use their equipment, and listen to their stories. • My friends and family, who now all know far more about Boosey & Hawkes’ clarinets than they ever wanted to. 3 Abstract Current literature agrees that British clarinet playing between c. 1930 and c. 1980 was linked to a particular clarinet manufacturer: Boosey & Hawkes. The unusually wide-bored 1010 clarinet is represented as particularly iconic of this period but scholars have not provided details of why this is so nor explored the impact of other B&H clarinets. This thesis presents an empirical overview of all clarinet manufacturing which took place at B&H (and Boosey & Co). -

Soprano Cornet

SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN (Under the Direction of Brandon Craswell) ABSTRACT The E-flat soprano cornet has served an indispensable role in the British brass band; it is commonly considered to be “the hottest seat in the band.”1 Compared to its popularity in Britain and Europe, the soprano cornet is not as familiar to players in North America or other parts of world. This document aims to offer young players who are interested in playing the soprano cornet in a brass band a more complete view of the instrument through the research of its historical roots, its artistic role in the brass band, important solo repertoire, famous players, approach to the instrument, and equipment choices. The existing written material regarding the soprano cornet is relatively limited in comparison to other instruments in the trumpet family. Research for this document largely relies on established online resources, as well as journals, books about the history of the brass band, and questionnaires completed by famous soprano cornet players, prestigious brass band conductors, and composers. 1 Joseph Parisi, Personal Communication, Email with Yanbin Chen, April 15, 2019. In light of the increased interest in the brass band in North America, especially at the collegiate level, I hope this project will encourage more players to appreciate and experience this hidden gem of the trumpet family. INDEX WORDS: Soprano Cornet, Brass Band, Mouthpiece, NABBA SOPRANO CORNET: THE HIDDEN GEM OF THE TRUMPET FAMILY by YANBIN CHEN Bachelor -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays. -

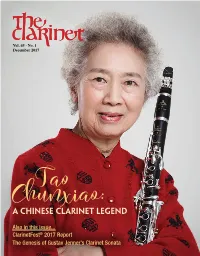

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017.