Berio Morton Feldman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

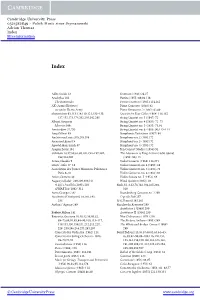

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is the extended form of six public lectures delivered in the Ernest Bloch Lecture Series from September 18 to October 23, 1989, in the Department of Music at the University of California at Berkeley. To my regret, the presentation of this expanded version, which for the most part I had finished by the end of 1992, is somewhat overdue, but not without good reason. For an American publication I found that I could not help but produce, if I may say so, a magnum opus, a summary of three decades of Bartók studies, thereby offering grateful, if belated, thanks to the University of California and to my colleagues and students at Berkeley. It was proba- bly the happiest time of my life: I had the honor not only of presenting the music of Béla Bartók but also, at a turning point in Bartók studies, of outlining the tasks awaiting future research on his oeuvre before the most resonant, expert audience I have ever met outside of my country, Hungary—the homeland of Bartók. Coming half a century after the death of the composer, this is the first book dedicated to the study of Bartók's compositional process to be based on the com- plete existing primary source material. Therefore, a great many things need to be accomplished simultaneously: a description of the sources (chapter 3) as well as the first reliable list of manuscripts (in the appendix); an extensive discussion of Bar- tók's sketches and drafts (chapters 4 and 7); an introduction to auxiliary research fields as for instance in paper studies (chapter 6). -

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

Invenzione Festival Berio

INVENZIONE FESTIVAL BERIO Du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 www.cnsmd-lyon.fr , Paris DES SIGNES DES : conception graphique conception Invenzione festival Berio du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 La musique n’est pas pressée : elle vit dans notre culture, le temps des arbres et des forêts, de la mer et des grandes villes. Luciano Berio Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Luciano Berio a marqué pour toujours la musique de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Son œuvre, sans frontières et d’une incroyable diversité, a mis à profit toutes les techniques, du sérialisme à l’électroacoustique. L’homme ne s’est laissé enfermer dans aucun clan, parti pris théorique ou gratuité abstraite. Son intelligence prend appui sur la vie, un esprit d’invention et une imagination généreuse. Il réinventa les continuités en gardant une curiosité insatiable pour les expériences exploratoires. Ses dialogues avec littérature, linguistique, anthropologie ou ethnomusicologie ont nourri son inventivité et c’est en tant que compositeur qu’il s’est approprié les matières qui le fascinaient afin d’en extraire des effets parfois fort éloignés de leur contexte d’origine. Berio a aussi sondé des domaines originaux et longtemps oubliés de notre culture occidentale, en particulier celui de la voix féminine qui a pris de plus en plus de place dans ses œuvres ; le chant impliquant un texte, Berio a collaboré avec des poètes tels que Sanguineti. Passionné par le potentiel des timbres instrumentaux, il a écrit une vaste série de pièces pour instruments solo, les fameuses Sequenza, puis s’est attaché dès les années 60 à explorer les plus improbables combinaisons de timbres. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

Rossini Propició El Futuro De La Ópera

www.proopera.org.mx • año XXVI • número 1 • enero – febrero 2018 • sesenta pesos ENTREVISTAS Andeka Gorrotxategi Óscar Martínez ENTREVISTAS EN LÍNEA Mojca Erdmann Nancy Fabiola Herrera Willy Anthony Waters FESTIVALES Cervantino XLV OBITUARIO Dmitri Hvorostovsky JohnJohn OsbornOsborn “Rossini“Rossini propiciópropició el futuro de la ópera”pro opera¾ DIRECTORIO REVISTA COMITÉ EDITORIAL Adriana Alatriste índice Luis Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba Andrea Labastida Charles H. Oppenheim 3 Carta del Presidente FUNDADOR Y DIRECTOR EMÉRITO CONCIERTOS Xavier Torres Arpi 4 Juan Diego Flórez: Canto a México EDITOR Charles H. Oppenheim 6 En breve 6 [email protected] CORRECCIÓN DE ESTILO CRÍTICA Darío Moreno 8 Otello en Bellas Artes COLABORAN EN ESTE NÚMERO 10 Ópera en México Othón Canales Treviño Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa Luis Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba PROTAGONISTAS Ingrid Haas 12 Andeka Gorrotxategi: Ramón Jacques “Me encantaría tener puestas José Noé Mercado todas las óperas de Puccini” David Rimoch Vladimiro Rivas Iturralde RESEÑA Gamaliel Ruiz 15 Arreglo de bodas en el Cenart José Andrés Tapia Osorio David Josué Zambrano de León 16 Ópera en los estados 15 www.proopera.org.mx. FESTIVALES CORRESPONSALES EN ESTE NÚMERO 20 Cervantino XLV Eduardo Benarroch Francesco Bertini Abigaíl Brambila ENTREVISTA Jorge Binaghi 22 Óscar Martínez: John Koopman Un cantante versátil Daniel Lara y un maestro ecléctico Gregory Moomjy Maria Nockin OBITUARIO Gustavo Gabriel Otero 25 Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017) Joel Poblete Roberto San Juan Ximena Sepúlveda PORTADA Massimo Viazzo 26 John Osborn: “Rossini propició el futuro de la ópera” FOTOGRAFIA Ana Lourdes Herrera ESTRENO 25 DISEÑO GRAFICO 32 La degradación de la burguesía: Ida Noemí Arellano Bolio The Exterminating Angel, desde Nueva York DISEÑO PÁGINA WEB TESTIMONIAL Christiane Kuri – Espacio Azul 34 Pro Ópera en Los Ángeles DISEÑO LOGO 36 México en el mundo Ricardo Gil Rizo IMPRESION ÓPERA EN EL MUNDO Grupo Gama. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

140117 WEB.Pdf

OPL – Aventure+ Vendredi / Freitag / Friday 17.01.2014 19:00 Grand Auditorium «Africa» Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Jonathan Stockhammer direction Angélique Kidjo voix Simon Stierle, Benjamin Schäfer timbales Après le concert / Im Anschluss an das Konzert Grand Foyer Mamadou Diabate Quartett Mamadou Diabate, Seydou «Kanazoe» Diabate balafon Zakaria Kone djembé Juan Garcia-Herreros guitare basse électrique Bitte beachten Sie, dass der Bus-Shuttle nach Trier erst im Anschluss an das «Plus» mit dem Mamadou Diabate Quartett abfährt. Traditional / Mzilikazi Khumalo (*1932) Five African Songs (arr. for orchestra by Péter Louis van Dijk from the choral arrangements by Mzilikazi Khumalo, 1992–1994) N° 1: «Banto Be-Afrika Hlanganani» (Mzilikazi Khumalo, 1990s) N° 2: «Bawo Thixo Somandla» (trad. Xhosa, 1960s/1970s) N° 3: «Sizongena Laph’emzini» (trad. Zulu, 1920s/1930s, 1940s/1950s) N° 4: «Ingoma ka Ntsikana» (The Hymn of Ntsikana / The Bell Song, trad. Xhosa, late 19th century) N° 5: «Akhala Amaqhude Amabili» (trad. Zulu, 1920s/1930s) 20’ Philip Glass (*1937) Ifè. Three Yorùbá Songs for Mezzo-Soprano and Orchestra (2013, création / Uraufführung; commande / Kompositionsauftrag Philharmonie Luxembourg & Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg) I. Olodumare II. Yemandja III. Oshumare 20’ — Philip Glass Concerto fantasy for two timpanists and orchestra (2000) I II Cadenza III 27’ Les liens entre le monde de la musique et notre banque sont anciens et multiples. Ils se traduisent par le soutien que nous avons apporté pendant de longues années à la production discographique de l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxem- bourg, notre rôle de mécène au lancement des programmes jeune public de la Philharmonie ou les nombreux concerts que nous accueillons au sein de notre auditorium. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

The King's Singers the King's Singers

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 3-21-1991 Concert: The King's Singers The King's Singers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation The King's Singers, "Concert: The King's Singers" (1991). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5665. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5665 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College ITHACA School of Music ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1990-91 THE KING'S SINGERS David Hurley, Countertenor Alastair Hume, Countertenor Bob Chilcott, Tenor Bruce Russell, Baritone Simon Carrington, Baritone Stephen Connolly, Bass I. Folksongs of North America THE FELLER FROM FORTUNE arranged by Robert Chilcott SHE'S LIKE THE SWALLOW I BOUGHT ME A CAT THE GIFT TO BE SIMPLE n. Great Masters of the English Renaissance Sacred Music from Tudor England TERRA TREMUIT William Byrd 0 LORD, MAKE THY SERVANT ELIZABETH OUR QUEEN (1543-1623) SING JOYFULLY UNTO GOD OUR STRENGTH AVE MARIA Robert Parsons (1530-1570) Ill. HANDMADE PROVERBS Toro Takemitsu (b. 1930) CRIES OF LONDON Luciano Berio (b. 1925) INTERMISSION IV. SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN OPERA Paul Drayton (b. 1944) v. Arrangements in Close Harmony Selections from the Lighter Side of the Repertoire Walter Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, March 21, 1991 8:15 p.m. The King's Singers are represented by IMG Artists, New York. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site

“Music of Our Time” When I worked at Columbia Records during the second half of the 1960s, the company was run in an enlightened way by its imaginative president, Goddard Lieberson. Himself a composer and a friend to many writers, artists, and musicians, Lieberson believed that a major record company should devote some of its resources to projects that had cultural value even if they didn’t bring in big profits from the marketplace. During those years American society was in crisis and the Vietnam War was raging; musical tastes were changing fast. It was clear to executives who ran record companies that new “hits” appealing to young people were liable to break out from unknown sources—but no one knew in advance what they would be or where they would come from. Columbia, successful and prosperous, was making plenty of money thanks to its Broadway musical and popular music albums. Classical music sold pretty well also. The company could afford to take chances. In that environment, thanks to Lieberson and Masterworks chief John McClure, I was allowed to produce a few recordings of new works that were off the beaten track. John McClure and I came up with the phrase, “Music of Our Time.” The budgets had to be kept small, but that was not a great obstacle because the artists whom I knew and whose work I wanted to produce were used to operating with little money. We wanted to produce the best and most strongly innovative new work that we could find out about. Innovation in those days had partly to do with creative uses of electronics, which had recently begun changing music in ways that would have been unimaginable earlier, and partly with a questioning of basic assumptions.