THE BASS CLARINET RECITAL with Copyright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

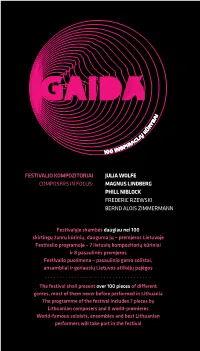

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

(Pdf) Download

ATHANASIOS ZERVAS | BIOGRAPHY BRIEF BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He holds a DM in composition and a MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with Frank Garcia, M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke, and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice “Bunky” Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner. Dr. Athanasios Zervas is an Associate Professor of music theory-music creation at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki Greece, Professor of Saxophone at the Conservatory of Athens, editor for the online theory/composition journal mus-e-journal, and founder of the Athens Saxophone Quartet. COMPLETE BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He has spent most of his career in Chicago and Greece, though his music has been performed around the globe and on dozens of recordings. He is a specialist on pitch-class set theory, contemporary music, composition, orchestration, improvisation, music of the Balkans and Middle East, and traditional Greek music. EDUCATION He holds a DM in composition and an MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen L. Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice ‘Bunky’ Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner; and jazz orchestration/composition with William Russo. RESEARCH + WRITING Dr. -

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President This concert will be available online for free streaming 2008–09 Student Recital Series and download on Thursday, February 19. The Edith L. and Robert Prostkoff Memorial Concert Series Visit www.instantencore.com/curtis after 12 noon and enter this download code in the upper-right corner of the webpage: Feb09CTour Forty-Fourth Student Recital: Curtis On Tour Click “Go” and follow the instructions on the screen to save music Wednesday, February 18 at 8 p.m. Field Concert Hall onto your computer. Divertimento for Violin and Piano Igor Stravinsky Next Student Recital Sinfonia (1882–1971) Friday, February 20 at 8 p.m. Danses suisses 20/21: The Curtis Contemporary Music Ensemble— Scherzo Second Viennese School, Program III Pas de deux: Adagio—Variation—Coda Field Concert Hall Josef Špaček, violin Kuok-man Lio, piano Berg Sieben frühe Lieder Amanda Majeski, soprano Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo Stravinsky Mikael Eliasen, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet String Quartet, Op. 3 From the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám David Ludwig Joel Link, violin (world premiere) (b. 1972) Bryan A. Lee, violin Secrets of Creation Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt, viola Turning of Time Camden Shaw, cello Labor of Life Floating Particles Schoenberg Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 Carpe Diem Charlotte Dobbs, soprano Allison Sanders, mezzo-soprano David Moody, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet William Short, bassoon Phantasy, Op. 47 Christopher Stingle, trumpet Elizabeth Fayette, violin Ryan Seay, trombone Pallavi Mahidhara, piano Benjamin Folk, percussion Josef Špaček, violin Programs are subject to change. Harold Hall Robinson, double bass Call the Recital Hotline, 215-893-5261, for the most up-to-date information. -

Jubiläen: Xenakis 2022 | Strawinsky 2021 Thema

NR. 86 FRÜHJAHR 2020 WWW.BOOSEY.DE RELAUNCH: Besuchen Sie JUBILÄEN: unseren YouTube-Kanal Xenakis 2022 | Strawinsky 2021 youtube.com/BooseyTube THEMA: KOMPONISTINNEN Mehr auf Seite 12 in Gegenwart und Vergangenheit hier im Heft EIN VOrwOrt IN KRISENZEITEN Als das vorliegende Heft konzipiert, die Arbeit daran be- gonnen wurde, war das alles so nicht vorauszusehen. Wir Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser, haben intensiv darüber nachgedacht, ob ein solches Maga- zin aktuell versandt werden sollte. Wie ersichtlich, lautete diese Wochen stellen einen Einschnitt dar, den niemand die Antwort, die wir uns gaben: Ja! Die durch das Corona- von uns vergessen wird. Wie so viele andere Lebensbereiche Virus ausgelöste Krankheit wird bezwungen werden, und wurde der internationale Musikbetrieb durch die Corona- unser Musikleben wird wieder erwachen, so wie wir es Pandemie im Innersten verwundet. Das, was unser Dasein kennen und lieben. Insofern ist dieses Heft auch ein Aus- ausmacht, kann plötzlich nicht mehr stattfinden: die Live- druck der Hoffnung, miteinander weiter Pläne zu schmieden, Darbietung vor Publikum und der persönliche Austausch Entdeckungen zu machen und die Musik in die Zukunft zu über Musik. Aufführungen mussten abgesagt werden; tragen. Es kann sein, dass zwischen Drucklegung von Heft Projekte, auf die wir lange hingearbeitet haben, wurden samt Beilagen und Ihrer Lektüre einzelne Ereignisse und vom Virus durchkreuzt. Ganz zu schweigen davon, dass Termine hinfällig geworden sind – vorläufig. so manche/r sich der Erfahrung von Krankheit und Verlust gegenübersieht. Viele Menschen und Institu tionen erleiden Wir bitten um Nachsicht, wünschen trotz allem eine gute immense Einbußen, Existenzen stehen auf dem Spiel, und Lektüre und freuen uns auf die weitere Zusammenarbeit die wirtschaftlichen Folgen sind nicht absehbar. -

Symphonic Dances

ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON 2019 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Fri 16, 8pm Sat 17, 6.30pm PRESENTING PARTNER Adelaide Town Hall 2 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Dalia Stasevska Conductor Fri 16, 8pm Louis Lortie Piano Sat 17, 6.30pm Adelaide Town Hall John Adams The Chairman Dances: Foxtrot for Orchestra Ravel Piano Concerto in G Allegramente Adagio assai Presto Louis Lortie Piano Interval Rachmaninov Symphonic Dances, Op.45 Non allegro Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) Lento assai - Allegro vivace Duration Listen Later This concert runs for approximately 1 hour This concert will be recorded for delayed and 50 minutes, including 20 minute interval. broadcast on ABC Classic. You can hear it again at 2pm, 25 Aug, and at 11am, 9 Nov. Classical Conversation One hour prior to Master Series concerts in the Meeting Hall. Join ASO Principal Cello Simon Cobcroft and ASO Double Bassist Belinda Kendall-Smith as they connect the musical worlds of John Adams, Ravel and Rachmaninov. The ASO acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and future. 3 Vincent Ciccarello Managing Director Good evening and welcome to tonight’s Notwithstanding our concertmaster, concert which marks the ASO debut women are significantly underrepresented of Finnish-Ukrainian conductor, in leadership positions in the orchestra. Dalia Stasevska. Things may be changing but there is still much work to do. Ms Stasevska is one of a growing number of young women conductors Girls and women are finally able to who are making a huge impression consider a career as a professional on the international orchestra scene. -

Darryl White CV.Pdf

Dr. Darryl A. White University of Nebraska-Lincoln 7932 Bancroft Ave. School of Music Lincoln, NE 68506 226 Westbrook Music Building (402)4899402 Lincoln, NE 68588-0100 (402)4722988 Current Position: Associate Professor of Trumpet University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1997-present Duties: Recruit and teach applied trumpet students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, coach student chamber ensembles, teach brass skills, and other related courses, perform in the Faculty Jazz Quartet, perform in the Faculty Brass Quintet Education: Doctoral of Musical Arts, 2001 University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado Full Tuition Minority Fellowship Recipient Master of Music Performance, 1991 Northwestern University Evanston, Illinois Graduate Assistant Bachelor of Music, 1987 Youngstown State University Youngstown, Ohio Full Tuition Luley Scholarship Recipient Teaching Previous Sabbatical Replacement, Spring of 1996 Appointments: University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado -Applied Trumpet -Weekly Master Classes Instructor of Trumpet, 1995-1997 University of Denver, Lamont School of Music Denver, Colorado -Applied Trumpet, undergraduate and graduate -Brass Pedagogy -Brass Performance Class -Aries Quintet in Residency -Faculty Jazz Quintet Clinician and Lecturer, 1994-2002 Mile High Jazz Festival Boulder, Colorado -Daily Master Classes -Daily Performances -Conducting Big Band and Small Group Instructor of Trumpet, 1993-1994 Mesa State College Grand Junction, Colorado -Applied Trumpet -Brass Pedagogy -History of American Popular Music -Music Appreciation -Jazz -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Thesis Submission

Rebuilding a Culture: Studies in Italian Music after Fascism, 1943-1953 Peter Roderick PhD Music Department of Music, University of York March 2010 Abstract The devastation enacted on the Italian nation by Mussolini’s ventennio and the Second World War had cultural as well as political effects. Combined with the fading careers of the leading generazione dell’ottanta composers (Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero and Ildebrando Pizzetti), it led to a historical moment of perceived crisis and artistic vulnerability within Italian contemporary music. Yet by 1953, dodecaphony had swept the artistic establishment, musical theatre was beginning a renaissance, Italian composers featured prominently at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse , Milan was a pioneering frontier for electronic composition, and contemporary music journals and concerts had become major cultural loci. What happened to effect these monumental stylistic and historical transitions? In addressing this question, this thesis provides a series of studies on music and the politics of musical culture in this ten-year period. It charts Italy’s musical journey from the cultural destruction of the post-war period to its role in the early fifties within the meteoric international rise of the avant-garde artist as institutionally and governmentally-endorsed superman. Integrating stylistic and aesthetic analysis within a historicist framework, its chapters deal with topics such as the collective memory of fascism, internationalism, anti- fascist reaction, the appropriation of serialist aesthetics, the nature of Italian modernism in the ‘aftermath’, the Italian realist/formalist debates, the contradictory politics of musical ‘commitment’, and the growth of a ‘new-music’ culture. In demonstrating how the conflict of the Second World War and its diverse aftermath precipitated a pluralistic and increasingly avant-garde musical society in Italy, this study offers new insights into the transition between pre- and post-war modernist aesthetics and brings musicological focus onto an important but little-studied era. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

Stockhausen Unterwegs Zu Wagner

Magdalena Zorn Stockhausen unterwegs zu Wagner Eine Studie zu den musikalisch-theologischen Ideen in Karlheinz Stockhausens Opernzyklus LICHT (1977–2003) wolke Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Förderungs- und Beihilfefonds Wissenschaft der VG WORT Erstausgabe [zgl.: Diss., Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 2014] © Magdalena Zorn alle Rechte vorbehalten Wolke Verlag Hofheim, 2016 Umschlaggestaltung: Friedwalt Donner, Alonissos unter Verwendung eines Fotos von Fulvio Zanettini, aus der Kölner Aufführung von Stockhausens SONNTAG AUS LICHT, 2011 ISBN 978-3-95593-065-3 www.wolke-verlag.de Inhalt Danksagung.................................................10 Einleitung...................................................11 Motive der Rezeptions- und Wirkungsgeschichte von LICHT ..........23 1. Die Vergleichskonstellation Stockhausen–Wagner .................23 1.1 LICHT als Kulminationspunkt der deutschen Fortschritts-Musikgeschichte . 29 1.2 LICHT zwischen neomittelalterlichem Mysterienspiel und kunstreligiösem Happening in der Nachfolge des Parsifal.........31 1.2.1 Zur Rezeptionsgeschichte des SAMSTAG ................31 1.2.2 Die szenische Uraufführung des MITTWOCH............37 Erster Analysekontext Stockhausens Fortschreibung der deutsch-österreichischen Musikgeschichte..............................................47 2. Stockhausen als Nachfolger von Adrian Leverkühn und Josef Knecht ..52 2.1 Thomas Mann und sein Wagner-Bild ........................52 2.1.1 Leiden und Größe Richard Wagners ....................52 2.1.2 Doktor Faustus – -

A Symphonic Psalm, After a Drama by René Morax King David

ELLIOT JONES MUSIC DIRECTOR A Symphonic Psalm, after a drama by René Morax Music by Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) Please silence all cellular phones and other electronic devices King David PART I 1. Introduction (Orchestra & Narrator) 2. The song of David, the shepherd: God shall be my shepherd kind. 3. Psalm: All praise to him, the Lord of glory, the everlasting God my helper. 4. Fanfare and entry of Goliath 5. Song of victory: David is great, the Philistines overthrown. Chosen of God is he. 6. Psalm: In the Lord I put my faith, I put my trust. 7. Psalm: O had I wings like a dove, then I would fly away and be at rest. 8. Song of the prophets: Man that is born of a woman lives but a little while. 9. Psalm: Pity me Lord, for I am weak. 10. Saul’s camp 11. Psalm: God, the Lord shall be my light and my salvation. What cause have I to fear? 12. Incantation of the Witch of Endor 13. March of the Philistines 14. The lament of Gilboa: Ah! Weep for Saul. 1 PART II ORCHESTRA 15. Song of the daughters of Israel: Sister, oh sing thy song! Never has God forsaken us. 16. The dance before the ark: Mighty God be with us, O splendor of the morn. FLUTE and PICCOLO CELLO Alexander Lipay, Paula Redinger Anne Gratz INTERMISSION OBOE and ENGLISH HORN BASS PART III Marquise Demaree Dylan DeRobertis 17. Song: Now my voice in song up-soaring shall loud proclaim my king afar. 18.