Sacher 19 Inhalt.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Russia ‘Reimagined’: Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky’s Renard (1915 -1916) © 2005 by Helen Kin Hoi Wong In his Souvenir sur Igor Stravinsky , the Swiss novelist Ramuz recalled his first impression of Stravinsky as a Russian man of possessiveness: What I recognized in you was an appetite and feeling for life, a love of all that is living.. The objects that made you act or react were the most commonplace... While others registered doubt or self-distrust, you immediately burst into joy, and this reaction was followed at once by a kind of act of possession, which made itself visible on your face by the appearance of two rather wicked-looking lines at the corner of your mouth. What you love is yours, and what you love ought to be yours. You throw yourself on your prey - you are in fact a man of prey. 1 Ramuz’s comment perhaps explains what make Stravinsky’s musical style so pluralistic - his desire to exploit native materials and adopt foreign things as if his own. When Stravinsky began working on the Russian libretto of Renard in 1915, he was living in Switzerland in exile, leaving France where he had established his career. As a Russian avant-garde composer of extreme folklorism (as demonstrated in the Firebird , Petrushka and the Rite ), Stravinsky was never on edge in France. His growing friendship with famous French artists such as Vati, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Cocteau and Claudel indicated that he was gradually being perceived as part of the French artistic culture. In fact, this change of perception on Stravinsky was more than socially driven, as his musical language by the end of the War (1918) had clearly transformed to a new type which adhered to the French popular taste (as manifested in L'Histoire du Soldat , Five Easy Pieces and Ragtime ). -

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President This concert will be available online for free streaming 2008–09 Student Recital Series and download on Thursday, February 19. The Edith L. and Robert Prostkoff Memorial Concert Series Visit www.instantencore.com/curtis after 12 noon and enter this download code in the upper-right corner of the webpage: Feb09CTour Forty-Fourth Student Recital: Curtis On Tour Click “Go” and follow the instructions on the screen to save music Wednesday, February 18 at 8 p.m. Field Concert Hall onto your computer. Divertimento for Violin and Piano Igor Stravinsky Next Student Recital Sinfonia (1882–1971) Friday, February 20 at 8 p.m. Danses suisses 20/21: The Curtis Contemporary Music Ensemble— Scherzo Second Viennese School, Program III Pas de deux: Adagio—Variation—Coda Field Concert Hall Josef Špaček, violin Kuok-man Lio, piano Berg Sieben frühe Lieder Amanda Majeski, soprano Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo Stravinsky Mikael Eliasen, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet String Quartet, Op. 3 From the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám David Ludwig Joel Link, violin (world premiere) (b. 1972) Bryan A. Lee, violin Secrets of Creation Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt, viola Turning of Time Camden Shaw, cello Labor of Life Floating Particles Schoenberg Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 Carpe Diem Charlotte Dobbs, soprano Allison Sanders, mezzo-soprano David Moody, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet William Short, bassoon Phantasy, Op. 47 Christopher Stingle, trumpet Elizabeth Fayette, violin Ryan Seay, trombone Pallavi Mahidhara, piano Benjamin Folk, percussion Josef Špaček, violin Programs are subject to change. Harold Hall Robinson, double bass Call the Recital Hotline, 215-893-5261, for the most up-to-date information. -

A Symphonic Psalm, After a Drama by René Morax King David

ELLIOT JONES MUSIC DIRECTOR A Symphonic Psalm, after a drama by René Morax Music by Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) Please silence all cellular phones and other electronic devices King David PART I 1. Introduction (Orchestra & Narrator) 2. The song of David, the shepherd: God shall be my shepherd kind. 3. Psalm: All praise to him, the Lord of glory, the everlasting God my helper. 4. Fanfare and entry of Goliath 5. Song of victory: David is great, the Philistines overthrown. Chosen of God is he. 6. Psalm: In the Lord I put my faith, I put my trust. 7. Psalm: O had I wings like a dove, then I would fly away and be at rest. 8. Song of the prophets: Man that is born of a woman lives but a little while. 9. Psalm: Pity me Lord, for I am weak. 10. Saul’s camp 11. Psalm: God, the Lord shall be my light and my salvation. What cause have I to fear? 12. Incantation of the Witch of Endor 13. March of the Philistines 14. The lament of Gilboa: Ah! Weep for Saul. 1 PART II ORCHESTRA 15. Song of the daughters of Israel: Sister, oh sing thy song! Never has God forsaken us. 16. The dance before the ark: Mighty God be with us, O splendor of the morn. FLUTE and PICCOLO CELLO Alexander Lipay, Paula Redinger Anne Gratz INTERMISSION OBOE and ENGLISH HORN BASS PART III Marquise Demaree Dylan DeRobertis 17. Song: Now my voice in song up-soaring shall loud proclaim my king afar. 18. -

The Soldier's Tale

STRAVINSKY The Soldier’s Tale (Complete) Tianwa Yang, Violin Fred Child, Narrator Jared McGuire, The Soldier Jeff Biehl, The Devil Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players JoAnn Falletta Igor Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) and Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (1878-1947) STRAVINSKY The Soldier’s Tale (1882-1971) Igor Stravinsky was the son of a distinguished bass in The Firebird with a red flag, was soon succeeded by The Soldier’s Tale soloist at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg, creator distaste for the new regime and the decision not to return of important rôles in new operas by Tchaikovsky and to Russia. Text by Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (1878-1947) Rimsky-Korsakov. He was born, the third of four sons, at In 1934 Stravinsky had taken out French citizenship English version by Michael Flanders and Kitty Black, revised by Pamela Berlin Oranienbaum on the Gulf of Finland in the summer of but five years later, with war imminent in Europe, he 1882. In childhood his ability in music did not seem moved to the United States, where he had already enjoyed Part I Part II exceptional, but he was able to study privately with considerable success. The death of his first wife allowed 1 Introduction: The Soldier’s March 1:52 # The Soldier’s March (reprise) – Rimsky-Korsakov, who became a particularly important him to marry a woman with whom he had enjoyed a long 2 Soldier: This isn’t a bad place to stop... 0:55 Narrator: Down a hot and dusty road... 1:42 influence after the death of Stravinsky’s strong-minded earlier association and the couple settled in Hollywood, $ Narrator: Now he comes to another land.. -

THE BASS CLARINET RECITAL with Copyright

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY THE BASS CLARINET RECITAL: THE IMPACT OF JOSEF HORÁK ON RECITAL REPERTOIRE FOR BASS CLARINET AND PIANO AND A LIST OF ORIGINAL WORKS FOR THAT INSTRUMENTATION A LECTURE RECITAL/PERFORMANCE DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE BEINEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSIC By Melissa Sunshine Simmons EVANSTON, IL June, 2009 © 2009 Melissa Sunshine Simmons ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2 ABSTRACT Instrumental and vocal recitals in the Western classical music tradition have been a part of society for centuries. The bass clarinet was developed in the late 18th century and gained widespread acceptance in the latter part of the 19th century as a viable orchestral instrument, but it did not follow suit into the recital tradition until the middle of the 20th century. In 1955, Josef Horák of the former Czechoslovakia presented a recital of music for bass clarinet and piano. It was the first of its kind. The lack of repertoire for the combination of bass clarinet and piano quickly became obvious. Horák devoted his career to working with many composers across the globe and developing a substantial body of works for the bass clarinet. He also performed in many different countries, bringing exposure to this new repertoire. His efforts have resulted in a significant and exponentially growing exposure to an instrument worthy of its own solo recital repertoire. This document examines the life of Josef Horák, his collaboration with pianist Emma Kovárnová, and the music written for their ensemble, Due Boemi di Praga. It explores their struggle to make music within the confines of Communist Czechloslovakia and their influence on the musical world outside of their native land. -

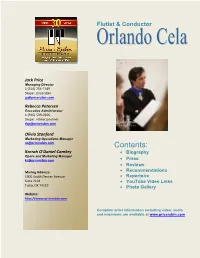

Flutist & Conductor

Flutist & Conductor Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Contents: Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Biography Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Press Reviews Mailing Address: Recommendations 1000 South Denver Avenue Repertoire Suite 2104 YouTube Video Links Tulsa, OK 74119 Photo Gallery Website: http://www.pricerubin.com Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Orlando Cela – Biography Venezuelan born musician Orlando Cela is committed to engaging audiences with lively performances that open new worlds of experience. Known for his engaging performances using imaginative programming, Orlando has premiering over 100 works, both as a flutist and as a conductor. In concert, Mr. Cela regularly offers short lively introductions to selected works, offering audiences entry points into unfamiliar works, so that listeners can easily connect the music with other life experience. As a flutist, Mr. Cela has performed at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian (Washington DC), the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston), and at the Center for New Music and Technologies at UC Berkeley. His credits abroad include concerts at the Zentrum Danziger (Berlin), the Espace des Femmes (Paris), and at the Musikverein (Vienna). As a collaborative artist, Mr. Cela has concertized with flutist Paula Robison, tabla player Samir Chatterjee, harpsichordist John Gibbons, and shen (mouth organ) virtuoso Hu Jianbing. To help expand the flute repertoire further, Orlando recently launched FluteLab, an online forum in which he answers composers’ questions about writing for the flute, posting answers and commentaries in engaging video clips to help the entire field and share the latest approaches and technical wizardry. -

Masterwork, Benefit Concert, and Miscellaneous Choral Works By

Three Dissertation Recitals: Masterwork, Benefit Concert, and Miscellaneous Choral Works by Adrianna L. Tam A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Conducting) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Eugene Rogers, Chair Professor Emeritus Jerry Blackstone Associate Professor Gabriela Cruz Associate Professor Julie Skadsem Associate Professor Gregory Wakefield Adrianna L. Tam [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1732-5974 © Adrianna L. Tam 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii RECITAL 1: DURUFLÉ REQUIEM 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes and Texts 2 RECITAL 2: FLIGHT: MERCY, JOURNEY & LANDING 6 Recital 2 Program 6 Recital 2 Program Notes and Texts 8 RECITAL 3: VIDEO COMPILATION 21 Recital 3 Program 21 Recital 3 Program Notes and Texts 23 ii ABSTRACT Three dissertation recitals were presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Conducting). The recitals included a broad range of repertoire, from the Baroque to modernity. The first recital was a performance of Duruflé’s Requiem, scored for chorus and organ, sung by a recital choir and soloists at Bethlehem United Church of Christ on Sunday, April 29, 2018. Scott VanOrnum played the organ, and University of Michigan (U-M) School of Music, Theatre & Dance doctoral students, Elise Eden and Leo Singer, joined as solo soprano and cellist, respectively. The second recital was a benefit concert held on January 27, 2019 at Ste. Anne de Detroit Catholic Church on behalf of the Prison Creative Arts Project. Guest singers and instrumentalists joined the core ensemble, Out of the Blue, to explore themes of mercy, journey, and landing. -

Stravinsky: the Soldier's Tale

Stravinsky Roman Simovic LSO Chamber Ensemble Malcolm Sinclair Supported by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The Soldier’s Tale (L’Histoire du soldat) (1918) Roman Simovic director / violin Edicson Ruiz double bass Andrew Marriner clarinet Rachel Gough bassoon Philip Cobb trumpet Dudley Bright trombone Neil Percy percussion Malcolm Sinclair spoken parts (The Narrator, The Soldier, The Devil) Recorded live in DSD 128fs, 31 October 2015, in the Jerwood Hall, LSO St Luke’s, London James Mallinson producer Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineer Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd recording engineer Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd audio editing, mixing and mastering © 2018 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK P 2018 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK 2 The Soldier's Tale (L'Histoire du soldat) Part I 1 Introduction. The Soldier's March "Down a hot and dusty road" 2’47’’ Soldier and fiddle "Phew... this isn't a bad sort of spot" 2 Music for Scene 1. Airs by a Stream 6’33’’ The Devil enters "Give me your fiddle" 3 The Soldier's March (Reprise) 4’01’’ The Soldier returns to his homeland "Hurray, here we are!" 4 Music for Scene 2. Pastorale 7’10’’ The Soldier confronts The Devil "Ah! You dirty cheat, it's you!" Little Pastorale The Soldier exploits the Book, but quickly recognises his foolishness "He took the book and began to read" 5 Airs by a Stream (Reprise): The Soldier remembers 4’05’’ The Soldier regains his violin "Please, kind sir, can I come in?" Music for Scene 3. -

Lawrence Morton Papers LSC.1522

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6d5nb3ht No online items Finding Aid for the Lawrence Morton Papers LSC.1522 Finding aid prepared by Phillip Lehrman, 2002; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 February 21. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Lawrence LSC.1522 1 Morton Papers LSC.1522 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Lawrence Morton papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1522 Physical Description: 42.5 Linear Feet(85 boxes, 1 oversize folder, 50 oversize boxes) Date (inclusive): 1908-1987 Abstract: Lawrence Morton (1904-1987) played the organ for silent movies and studied in New York before moving to Los Angeles, California, in 1940. He was a music critic for Script magazine, was the executive director of Evenings on the Roof, director of the Ojai Music Festival and curator of music at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The collection consists of books, articles, musical scores, clippings, manuscripts, and correspondence related to Lawrence Morton and his activities and friends in the Southern California music scene. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. -

Repetition and the Façade of Discontinuity In

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music ACTIVE STASIS: REPETITION AND THE FAÇADE OF DISCONTINUITY IN STRAVINSKY’S HISTOIRE DU SOLDAT (1918) A Thesis in Music Theory by Richard Desinord © 2016 Richard Desinord Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2016 1 The thesis of Richard Desinord was reviewed and approved* by the following: Maureen A. Carr Distinguished Professor of Music Thesis Advisor Eric J. McKee Professor of Music Marica A. Tacconi Professor of Music Graduate Officer and Associate Director of the School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT Igor Stravinsky’s (1882-1971) early works are often depicted as repetitive and regressive with regard to its thematic development and formal structure. His penchant for mosaic-like constructs that rely on the recurrence of unchanged blocks of sound and their subsequent juxtapositions defined his practice and enabled Stravinsky to seek out new ways of composing. In the music of other composers repetition was largely reliant upon differences in successive appearances that provided a sense of growth and direction from beginning to end. Stravinsky instead often depended on the recurrence of unchanged fragments and their interactions with other repetitive patterns across larger spans of his works. This thesis focuses on the use of repetition as an agent of progress in order to dispel lingering myths of the discontinuous elements in Stravinsky’s Histoire du soldat (1918). Following the work of Peter van den Toorn and Gretchen Horlacher, I examine repetition and block form as both static entities and embryonic figures, and the roles they play in musical development. -

Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky

Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja 149 Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky Heikki Poroila Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Helsinki 2012 Julkaisija Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys Toimitustyö ja ulkoasu Heikki Poroila © Heikki Poroila 2012 01.4 POROILA , HEIKKI Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky : teosten yhtenäistettyjen nimekkeiden ohjeluettelo / Heikki Poroila. – Helsinki : Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys, 2012. – 30 s. : kuv. – (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistyksen julkaisusarja, ISSN 0784-0322 ; 149). ISBN 978-952-5363-48-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-5363-48-7 (PDF) 2 Yhtenäistetty Igor Stravinsky Todellinen kosmopoliitti Igor Fjodorovitš STRAVINSKY (18.6.1882 - 7.6.1971), kuten säveltäjä itse halusi nimensä kir- joittaa asetuttuaan Yhdysvaltoihin asumaan, syntyi Venäjällä muusikkosukuun, mutta lähti jo ennen Lokakuun vallankumousta maailmalle. Stravinsky palasi synnyinmaahansa vasta elä- mänsä loppupuolella, silloinkin vain käväisemään. Stravinsky saavutti menestystä ja kuuluisuutta jo nuorena miehenä. Vuonna 1913 järjes- tetty Le sacre du printemps -teoksen ensiesityksen skandaali oli kuin varmistus paikalle vuo- sisadan modernismin eturivissä. Säveltäjän myöhempi kehitys oli täynnä melkoisia käänteitä, ja hän on itsekin puhunut selkeistä vaiheista. ”Venäläisen” kauden jälkeen seurasi ”eurooppa- lainen” vaihe, joka muuttui monen ällistykseksi uusklassisismiksi, paluuksi menneille vuo- sisadoille. Stravinsky sävelsi myös runsaasti ortodoksiseen uskontoon kytkeytynyttä musiik- kia liityttyään vuonna 1926 takaisin kirkon jäseneksi. Tämä uskonnollisuus -

Bass Clarinet Essentials MATTHIAS HÖFER & MANAMI SANO Bass Clarinet Essentials T.T

bass clarinet essentials MATTHIAS HÖFER & MANAMI SANO bass clarinet essentials T.T. 72:35 OTHMAR SCHOECK (1886–1957) 1 – 3 Sonate für Bassklarinette und Klavier op.41 – Werner Reinhart gewidmet – (Breitkopf&Härtel) 1 I. Gemessen 05:28 2 II. Bewegt 04:49 3 III. Bewegt 03:26 PAUL HINDEMITH (1895–1963) 4 – 5 Sonate (1938) für Fagott und Piano (Fassung für Bassklarinette und Klavier) (Schott Verlag Mainz, 1939; © mit Genehmigung von SCHOTT MUSIC, Mainz - Germany) 4 I. Leicht bewegt 02:07 5 II. Langsam-Marsch-Pastorale 06:41 ADOLF BUSCH (1891–1952) 6 – 9 Suite d-Moll für Bassklarinette solo op. 37a (1926) (Amadeus Verlag, 1980) 6 I. Andante tranquillo 01:13 7 II. Adagio 02:47 8 III. Scherzo 06:33 9 IV. Vivace 05:54 EUGÈNE BOZZA (1905–1991) 05:20 10 Ballade (1939) for bass clarinet and piano – Dedié aux Clarinettistes: R.M.Arey, J.E.Elliott, M.Fossenkemper, E.Schmachtenberg and G.E.Waln- (Southern Music Company) ERNST KRENEK (1900–1991) 02:35 11 Prelude (Allegro ma non troppo, vigoroso) (Manuskript) – Dedicated to Werner Reinhart in the old spirit of cordial friendship and with the most sincere wishes – St.Paul, Minnesota, February, 5, 1944 THORNTON WINSLOE = ERNST KRENEK 12 – 14 Sonatine for bass clarinet with piano accompaniment (School Music op. 85(A),d (1938 - 1939)) 12 I. Allegretto moderato 02:42 13 II. Andantino 02:20 14 III. Allegro 02:03 (Belwin, 1939 und UE, 2005) ALOIS HÁBA (1893–1973) 15 – 18 Suite für Bassklarinette und Klavier op. 100 (Musikedition Nymphenburg 2001) 15 I. Allegretto animato 01:20 16 II.