Repetition and the Façade of Discontinuity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Russia ‘Reimagined’: Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky’s Renard (1915 -1916) © 2005 by Helen Kin Hoi Wong In his Souvenir sur Igor Stravinsky , the Swiss novelist Ramuz recalled his first impression of Stravinsky as a Russian man of possessiveness: What I recognized in you was an appetite and feeling for life, a love of all that is living.. The objects that made you act or react were the most commonplace... While others registered doubt or self-distrust, you immediately burst into joy, and this reaction was followed at once by a kind of act of possession, which made itself visible on your face by the appearance of two rather wicked-looking lines at the corner of your mouth. What you love is yours, and what you love ought to be yours. You throw yourself on your prey - you are in fact a man of prey. 1 Ramuz’s comment perhaps explains what make Stravinsky’s musical style so pluralistic - his desire to exploit native materials and adopt foreign things as if his own. When Stravinsky began working on the Russian libretto of Renard in 1915, he was living in Switzerland in exile, leaving France where he had established his career. As a Russian avant-garde composer of extreme folklorism (as demonstrated in the Firebird , Petrushka and the Rite ), Stravinsky was never on edge in France. His growing friendship with famous French artists such as Vati, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Cocteau and Claudel indicated that he was gradually being perceived as part of the French artistic culture. In fact, this change of perception on Stravinsky was more than socially driven, as his musical language by the end of the War (1918) had clearly transformed to a new type which adhered to the French popular taste (as manifested in L'Histoire du Soldat , Five Easy Pieces and Ragtime ). -

Thesis October 11,2012

Demystifying Galina Ustvolskaya: Critical Examination and Performance Interpretation. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 Submitted in partial requirement for the Degree of PhD in Performance Practice at the Goldsmiths College, University of London 1 Declaration The work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been presented for any other degree. Where the work of others has been utilised this has been indicated and the sources acknowledged. All the translations from Russian are my own, unless indicated otherwise. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 2 Note on transliteration and translation The transliteration used in the thesis and bibliography follow the Library of Congress system with a few exceptions such as: endings й, ий, ый are simplified to y; я and ю transliterated as ya/yu; е is е and ё is e; soft sign is '. All quotations from the interviews and Russian publications were translated by the author of the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis presents a performer’s view of Galina Ustvolskaya and her music with the aim of demystifying her artistic persona. The author examines the creation of ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ by critically analysing Soviet, Russian and Western literature sources, oral history on the subject and the composer’s personal recollections, and reveals paradoxes and parochial misunderstandings of Ustvolskaya’s personality and the origins of her music. Having examined all the available sources, the author argues that the ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ was a self-made phenomenon that persisted due to insufficient knowledge on the subject. In support of the argument, the thesis offers a performer’s interpretation of Ustvolskaya as she is revealed in her music. -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

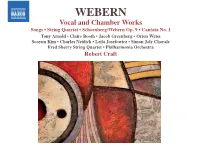

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 12:06 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon Volume 26, numéro 1, 2005 Résumé de l'article Le processus compositionnel de Stravinsky durant sa période néo-classique est URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013243ar ici mis en relief et étudié par le biais des esquisses, brouillons et autres copies DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar manuscrites de la Piano-Rag-Music. Ces autographes révèlent le matériel initial du compositeur, ses méthodes de travail, l’ampleur de ses préoccupations Aller au sommaire du numéro compositionnelles et les conditions étonnantes d’assemblage de l’œuvre. D’ailleurs, elles confirment que la fusion entre les trois éléments distincts opérée dans le titre de l’ouvrage par le trait d’union définit à la fois le contenu Éditeur(s) de l’œuvre et son objectif. La virtuosité pianistique et la vitalité rythmique de l’improvisation de type ragtime sont synthétisés en une forme musicale pure Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités qui est ni conventionnelle ni hybride, mais plutôt une résultante du matériel canadiennes en soi. ISSN 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gordon, T. (2005). Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music. Intersections, 26(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des universités canadiennes, 2006 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

International Sales

Mongrel Media Presents MADS MIKKELSEN ANNA MOUGLALIS COCO CHANEL & IGOR STRAVINSKY Afilm by JAN KOUNEN (1h 55 min., France, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS Paris 1913 At the Theatre Des Champs-Elysées, Igor Stravinsky premieres his The Rite Of Spring. Coco Chanel attends the premiere and is mesmerized…But the revolutionary work is too modern, too radical: the enraged audience boos and jeers. A near riot ensues. Stravinsky is inconsolable. Seven years later, now rich, respected and successful, Coco Chanel meets Stravinsky again - a penniless refugee living in exile in Paris after the Russian Revolution. The attraction between them is immediate and electric. Coco offers Stravinsky the use of her villa in Garches so that he will be able to work, and he moves in straight away, with his children and consumptive wife. And so a passionate, intense love affair between two creative giants begins... The production of Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky had the support of Karl Lagerfeld and CHANEL who have generously made available their archives and collections. CHANEL lent several original garments and accessories to be worn by Mademoiselle Anna Mouglalis in the role of Mademoiselle Chanel, and Karl Lagerfeld specially created a ‘timeless’ suit and an embroidered evening dress for the scene recreating the legendary and scandalous 1913 performance of The Rite Of Spring. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Sacher 19 Inhalt.Qxp

Music and Letters for Stravinsky’s Ragtime for Eleven Instruments by Glenda Dawn Goss Towards the end of World War I, Stravinsky’s well-timed foray into Amer- ican rag inspired Ragtime for Eleven Instruments (1918). There is consider- able misinformation about these 178 measures, due in part to their creator. It is thus worth considering the sources in the Igor Stravinsky Collection of the Paul Sacher Foundation for the light they shed on the work. – Sketchbook V. A clothbound book, 17 ϫ 20 cm, blue and gold covers with vertical stripes, 160 unnumbered, unlined leaves; a watermark of a tree sur- rounded by a nine-post fence; green, blue, and cream-checked endpapers; a blind stamp on the first endpaper’s verso. This little volume contains twenty-eight pages pertinent to Ragtime, be- ginning with motives on pp. [34–39]: ? A A A A- A A A A- A A A A A- A A A A- Example 1 Yet the pages’ changing meters do not fit a work known for its unvarying 4/4. Only on pp. [43–64] do Ragtime sketches begin in earnest and show how imprecise is the term “sketchbook” (Example 2). To be sure, there are snippets and fragments, hallmarks of Ragtime’s “trio”: a fixed bass; a syn- copated figure similar to Example 1; half-note chords highlighted in pencil. There is also a hymn-like theme marked “Trombono,” repeated on p. [46] for flute, trombone, and cornet and on p. [47] for trombone alone, then for flute and cornet. The theme’s length and prominence imbue it with unmis- takable importance.