Mikhail Druskin's IGOR STRAVINSKY: HIS LIFE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

The St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic Innovative Dynamic

Innovative Dynamic Progressive Unique TheJeffery St. Meyer, Petersburg Artistic Director Chamber & Principal Philharmonic Conductor The St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic was founded in 2002 to St.create Petersburg and encourage cultural exchange Chamber between the United Philharmonic States and Russia and has become St. Petersburg’s most exciting and in- “The St. Petersburg novative chamber orchestra. Since its inception, the St. PCP has performed in the major concert halls of the city and has been pre- sentedAbout in its most important festivals. The orchestra’s unique and Chamber Philharmonic progressive programming has distinguished it from the many orches- tras of the city. It has performed over 130 works, including over has become an integral a dozen world premieres, introduced St. Petersburg audiences to more than 30 young performers, conductors and composers from part of the city’s culture” 15 different countries (such up-and-coming stars as Alisa Weilerstein, cello), and performed works by nearly 20 living American compos- ers, including Russian premieres of works by Pulitzer Prize-winning American composers Steve Riech, Steven Stucky and John Adams. Festival Appearances: Symphony Space, Wall-to-Wall Festival, “Behind the Wall”, 2010 “The orchestra 14th International Musical Olympus Festival, 2009 & 2010 International New Music Festival “Sound Ways”, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 demonstrates splendid 43rd International Festival St. Petersburg “Musical Spring”, 2006 5th Annual Festival “Japanese Spring in St. Petersburg”, 2005 virtuosity” “Avant-garde in our Days” Music Festival, 2003 Halls: Symphony Space, New York City Academic Capella Hall of Mirrors, Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace Hermitage Theatre “Magnificent” Maly Sal (Glinka) of the Philharmonic Shuvalovksy Palace Hall, Fontanka River St. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

DRJ 45 1 Bookreviews 118..139

under-represented in popular dance research. Hutchinson, Sydney. 2007. From Quebradita to Sunday Serenade is a weekly social dance geared Duranguense: Dance in Mexican American toward mature Caribbean British immigrants, Youth Culture. Tucson, AZ: University of predominantly from Jamaica. Dodds argues Arizona Press. that community at this event is created through Morris, Gay. 2009. “Dance Studies/Cultural inclusion (of multiple music genres, dance Studies.” Dance Research Journal 41(1): styles, and people from varying economic back- 82–100. grounds) as an antidote to the exclusion that Nájera-Ramírez, Olga, Norma E. Cantú, and many of these immigrants have experienced in Brenda M. Romero, eds. 2009. Dancing British society. Many questions arose for me Across Borders: Danzas y Bailes Mexicanos. that were not answered in this chapter—such Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. as how gender roles were played out at this Oliver, Cynthia. 2010. “Rigidigidim de Bamba dance. I suspect, however, that such outstanding de: A Calypso Journey from Start to ...” In questions were a sign of how well Dodds had Making Caribbean Dance: Continuity and nurtured my investment in this community Creativity in Island Cultures, edited by rather than an indication of any real shortcom- Susanna Sloat, 3–10. Gainesville, FL: ings in her scholarship. University Press of Florida. The larger questions that I found myself Savigliano, Marta Elena. 2009. “Worlding Dance pondering at the end of the book are issues I and Dancing Out There in the World.” In hope all dance ethnographers grapple with on Worlding Dance, edited by Susan Leigh Foster, an ongoing basis. In none of these case studies 163–90. -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

Influence of Commedia Dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟S Suite Italienne D.M.A

Influence of Commedia dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi, B.M., M.A., M.B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Kia-Hui Tan, Advisor Paul Robinson Mark Rudoff Copyright by Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi 2009 Abstract Suite Italienne for violin and piano (1934) by Stravinsky is a compelling and dynamic work that is heard in recitals and on recordings. It is based on Stravinsky‟s music for Pulcinella (1920), a ballet named after a 16th century Neapolitan stock character. The purpose of this document is to examine, through the discussion of the history and characteristics of Commedia dell‟Arte ways in which this theatre genre influenced Stravinsky‟s choice of music and compositional techniques when writing Pulcinella and Suite Italienne. In conclusion the document proposes ways in which the violinist can incorporate the elements of Commedia dell‟Arte that Stravinsky utilizes in order to give a convincing and stylistic performance. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Kia-Hui Tan and my committee members, Dr. Paul Robinson, Prof. Mark Rudoff, and Dr. Jon Woods. I also would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of my first advisor, the late Prof. Michael Davis. iii Vita 1986………………………………………….B.M., Manhattan School of Music 1988-1989……………………………….…..Visiting International Student, Utrecht Conservatorium 1994………………………………………….M.A., CUNY, Queens College 1994-1995……………………………………NEA Rural Residency Grant 1995-1996……………………………………Section violin, Louisiana Philharmonic 1998………………………………………….M.B.A., Tulane University 1998-2008……………………………………Part-time instructor, freelance violinist 2001………………………………………….Nebraska Arts Council Touring Artists Roster 2008 to present………………………………Lecturer in Music, Salisbury University Publications “Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne Unmasked.” Stringendo 25.4 (2009):19. -

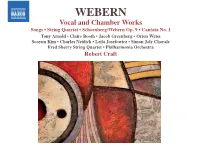

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’S Neoclassical Keyboard Works

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’s Neoclassical Keyboard Works Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Mueller, Peter M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 03:29:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626657 TOWARD A THEORY OF FORMAL FUNCTION IN STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICAL KEYBOARD WORKS by Peter M. Mueller __________________________ Copyright © Peter M. Mueller 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire.