61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

03 May 2021.Pdf

3 May 2021 12:01 AM Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762) Concerto grosso in D minor, Op 7 No 2 La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken (conductor) DEWDR 12:10 AM Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Prelude for guitar no.1 in E minor Norbert Kraft (guitar) CACBC 12:15 AM Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 2 Songs: When Night Descends in silence; Oh stop thy singing maiden fair Fredrik Zetterstrom (baritone), Tobias Ringborg (violin), Anders Kilstrom (piano) SESR 12:24 AM Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Serenade no 2 in G minor for violin & orchestra, Op 69b Judy Kang (violin), Orchestre Symphonique de Laval CACBC 12:33 AM Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Polonaise No.2 in E major from (S.223) Ferruccio Busoni (piano) SESR 12:43 AM Giovanni Gabrieli (1557-1612) Exaudi me, for 12 part triple chorus, continuo and 4 trombones Danish National Radio Chorus, Copenhagen Cornetts & Sackbutts, Lars Baunkilde (violone), Soren Christian Vestergaard (organ), Bo Holten (conductor) DKDR 12:50 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Symphony no 104 in D major "London" (H.1.104) Tamas Vasary (conductor), Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra HUMR 01:15 AM Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) Piano Quintet in E major, Op 15 Daniel Bard (violin), Tim Crawford (violin), Mark Holloway (viola), Chiara Enderle (cello), Paolo Giacometti (piano) CHSRF 01:47 AM Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) "Hor che Apollo" - Serenade for Soprano, 2 violins & continuo Susanne Ryden (soprano), Musica Fiorita, Daniela Dolci (director) DEWDR 02:01 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Ma mère l'oye (suite) WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:18 AM Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Concerto for Two Pianos in D minor, FP 61 Lucas Jussen (piano), Arthur Jussen (piano), WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:38 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Symphony No. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

The Chesterian (1915-1961)

Introduction to: Liesbeth Hoedemaeker, The Chesterian (1915-1940, 1947-1961) Répertoire international de la presse musicale (www.ripm.org) Copyright © 2013 RIPM Consortium Ltd The Chesterian 1915-1961 The Chesterian [CHE], one of England’s most important journals dealing with the development of musical composition and style during the first half of the twentieth century, was published by J. & W. Chester, the well-known music publisher. The journal1 was issued in two series, the first from 1915-1919; the second, titled New Series, from 1919-1961. Publication was interrupted from 1940 to 1947, years of the Second World War. The journal’s format is small: ca. 11 x 19 cm. The volumes were published annually from September to July. The first series consists of twenty, sixteen-page issues containing 320 numbered pages. The New Series consists of two- hundred-and-eight issues and 8,632 pages, including unnumbered pages. The number of annual issues begins at eight per volume in September 1919; declines to six in September 1932 until 1939; and, after the interruption, to four issues in 1947. The cover pages often contain information, such as lists of contributors, opinions of subscribers, contents of earlier issues and advertisements. The appearance of the New Series sparked sufficient interest to be recognized in the New York Tribune which offered an extensive preliminary list of contributors, citing letters as being of special interest: A feature of this magazine will be letters from various music centres containing information of current musical events. Ernest Newman, René Chalupt, Guido M. Gatti and Adolfo Salazar will be the respective contributors of letters from London, Paris, Italy and Spain.2 The journal’s appearance was also noted in The Musical Times: The Chesterian will be a … very readable little circular … In its new form it will appear eight times in the year. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

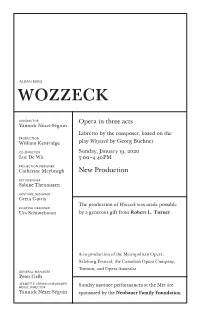

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J.