Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

Jean-Guihen Queyras Violoncello

JEAN-GUIHEN QUEYRAS VIOLONCELLO Biography Curiosity, diversity and a firm focus on the music itself characterize the artistic work of Jean- Guihen Queyras. Whether on stage or on record, one experiences an artist dedicated completely and passionately to the music, whose humble and quite unpretentious treatment of the score reflects its clear, undistorted essence. The inner motivations of composer, performer and audience must all be in tune with one another in order to bring about an outstanding concert experience: Jean-Guihen Queyras learnt this interpretative approach from Pierre Boulez, with whom he established a long artistic partnership. This philosophy, alongside a flawless technique and a clear, engaging tone, also shapes Jean-Guihen Queyras’ approach to every performance and his absolute commitment to the music itself. His approaches to early music – as in his collaborations with the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin – and to contemporary music are equally thorough. He has given world premieres of works by, among others, Ivan Fedele, Gilbert Amy, Bruno Mantovani, Michael Jarrell, Johannes-Maria Staud, Thomas Larcher and Tristan Murail. Conducted by the composer, he recorded Peter Eötvös’ Cello Concerto to mark his 70th birthday in November 2014. Jean-Guihen Queyras was a founding member of the Arcanto Quartet and forms a celebrated trio with Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov; the latter is, alongside Alexandre Tharaud, a regular accompanist. He has also collaborated with zarb specialists Bijan and Keyvan Chemirani on a Mediterranean programme. The versatility in his music-making has led to many concert halls, festivals and orchestras inviting Jean-Guihen to be Artist in Residence, including the Concertgebouw Amsterdam and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Vredenburg Utrecht, De Bijloke Ghent and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg. -

The Universi ~

The Universi ~ Presents THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor WEDNESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 8, 1971 , AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM "J eux" (Games) DEBUSSY "The Miraculous Mandarin" (Complete Music of the Ballet-Pantomime) INTERMISSION Symphony No.3 in E-flat major, Op. 97 ("Rhenish") SCHUMANN Lebhaft Scherzo : seh r massig Nicht schnell Feierlich Lebhaft Columbia, Epic, and Angel R eco rds The Cleveland Orchestra has appeared here on twenty-three previous occasions since 1935 . Fourth Concert Ninety-third Annual Choral Union Series Complete Programs 3753 PROGRAM OTES "Jeux" (Games ) C LAUDE DEBUSSY Debussy composed felix in 1912, on an idea and scenario by the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. It was produced on May 15, 1913, at the TIt/3d.tre des Champs Elysees, Paris, by the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev. The choreography was by Nijinsky, who also danced the role of the Young Man. f elix is Debussy's most "modern" composition, the most advanced in method and style , the most prophetic of such future d ~ vcJopm e nt s as the pointillism of Webern and the search for new sonorities by electronic means. The characteristic whole-tone scale of Debussy is here employed toward almost atonal ends. The gigantic orchestral apparatus is used with the utmost eco nomy as well as imagina tive subtlety. It is interesting to lea rn that the conductor of the present performances, Pierre Boulez, studied f eliX with special care when he was a student of Oliver Messiaen. For the sake of historical correctness, one must give the "argument" that was published at the time of the premiere, the synopsis of the action as conceived by Nijinsky and transformed into sound by Debussy. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Pierre Boulez Rituel

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Pierre Boulez Born March 26, 1925, Montbrison, France. Currently resides in Paris, France. Rituel (In memoriam Bruno Maderna) Boulez composed this work in 1974 and 1975, and conducted the first performance on April 2, 1975, in London. The score calls for three flutes and two alto flutes, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets, E- flat clarinet and bass clarinet, alto saxophone, four bassoons, six horns, four trumpets, four trombones, six violins, two violas, two cellos, and a percussion battery consisting of tablas, japanese bells, woodblocks, japanese woodblock, maracas, tambourine, sizzle cymbal, turkish cymbal, chinese cymbal, cow bells, snare drums (with and without snares), guiros, bongo, claves, maracas-tubes, triangles, hand drums, castanets, temple blocks, tom-toms, log drum, conga, gongs, and tam-tams. Performance time is approximately twenty- five minutes. Bruno Maderna died on November 13, 1973. For many years he had been a close friend of Pierre Boulez (and a true friend of all those involved in new music activities) and a treasured colleague; like Boulez, he had made his mark both as a composer and as a conductor. “In fact, to get any real idea of what he was like as a person,” Boulez wrote at the time of his death, “the conductor and the composer must be taken together; for Maderna was a practical person, equally close to music whether he was performing or composing.” In 1974 Boulez began Rituel as a memorial piece in honor of Maderna. (In the catalog of his works, Rituel follows . explosante-fixe . ., composed in 1971 as a homage to Stravinsky.) The score was completed and performed in 1975. -

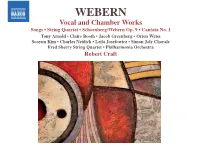

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

Cso at the Movies 2014/15 Series Concludes with Silent Film Classic, Metropolis

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: May 8, 2015 Eileen Chambers, 312-294-3092 Rachelle Roe, 312-294-3090 Photos Available By Request [email protected] CSO AT THE MOVIES 2014/15 SERIES CONCLUDES WITH SILENT FILM CLASSIC, METROPOLIS May 29 at 8 p.m. CHICAGO—The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 2014/15 CSO at the Movies series concludes with a screening of Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis on Friday, May 29 at 8 p.m. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), led by conductor Cristian Măcelaru, will accompany Giorgio Moroder’s abridged version of the film with a live performance of a score compiled by John Goberman and that includes music by Schoenberg, Grieg and Bartók. Fritz Lang’s genre-defining science fiction film debuted in 1927 and has since been restored and rereleased all over the world. The film is set in a futuristic city whose citizens, divided into two classes, find that their conflicts are mediated by an unexpected source. Film critic Roger Ebert described Metropolis as doing “what many great films do, creating a time, place and characters so striking that they become part of our arsenal of images for imagining the world… and the result is one of those films without which many others cannot be fully appreciated.” Because of its production as a silent film, the score for Metropolis is reinvented with each screening of the film. The CSO will use the score compiled by TV and film producer John Goberman, the creator of the Emmy Award-winning show Live from Lincoln Center. Goberman’s compiled score for Metropolis includes sections of Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night and two of the composer’s chamber symphonies, Bartok’s String Quartet No. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

61 CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS and CONFLICT with STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations a Close Friendship Between Arthur Lourié A

CHAPTER 4 CONNECTIONS AND CONFLICT WITH STRAVINSKY Connections and Collaborations A close friendship between Arthur Lourié and Igor Stravinsky began once both had left their native Russian homeland and settled on French soil. Stravinsky left before the Russian Revolution occurred and was on friendly terms with his countrymen when he departed; from the premiere of the Firebird (1910) in Paris onward he was the favored representative of Russia abroad. "The force of his example bequeathed a russkiv slog (Russian manner of expression or writing) to the whole world of twentieth-century concert music."1 Lourié on the other hand defected in 1922 after the Bolshevik Revolution and, because he had abandoned his position as the first commissar of music, he was thereafter regarded as a traitor. Fortunately this disrepute did not follow him to Paris, where Stravinsky, as did others, appreciated his musical and literary talents. The first contact between the two composers was apparently a correspondence from Stravinsky to Lourié September 9, 1920 in regard to the emigration of Stravinsky's mother. The letter from Stravinsky thanks Lourié for previous help and requests further assistance in selling items from Stravinsky's 1 Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the 61 62 apartment in order to raise money for his mother's voyage to France.2 She finally left in 1922, which was the year in which Lourié himself defected while on government business in Berlin. The two may have met for the first time in 1923 when Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat was performed at the Bauhaus exhibit in Weimar, Germany. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F. -

Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 12:06 Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music Tom Gordon Volume 26, numéro 1, 2005 Résumé de l'article Le processus compositionnel de Stravinsky durant sa période néo-classique est URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1013243ar ici mis en relief et étudié par le biais des esquisses, brouillons et autres copies DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar manuscrites de la Piano-Rag-Music. Ces autographes révèlent le matériel initial du compositeur, ses méthodes de travail, l’ampleur de ses préoccupations Aller au sommaire du numéro compositionnelles et les conditions étonnantes d’assemblage de l’œuvre. D’ailleurs, elles confirment que la fusion entre les trois éléments distincts opérée dans le titre de l’ouvrage par le trait d’union définit à la fois le contenu Éditeur(s) de l’œuvre et son objectif. La virtuosité pianistique et la vitalité rythmique de l’improvisation de type ragtime sont synthétisés en une forme musicale pure Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités qui est ni conventionnelle ni hybride, mais plutôt une résultante du matériel canadiennes en soi. ISSN 1911-0146 (imprimé) 1918-512X (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gordon, T. (2005). Great-Rag-Sketches, Source Study for Stravinsky's Piano-Rag-Music. Intersections, 26(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013243ar Copyright © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des universités canadiennes, 2006 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne.