Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’S Neoclassical Keyboard Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

The St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic Innovative Dynamic

Innovative Dynamic Progressive Unique TheJeffery St. Meyer, Petersburg Artistic Director Chamber & Principal Philharmonic Conductor The St. Petersburg Chamber Philharmonic was founded in 2002 to St.create Petersburg and encourage cultural exchange Chamber between the United Philharmonic States and Russia and has become St. Petersburg’s most exciting and in- “The St. Petersburg novative chamber orchestra. Since its inception, the St. PCP has performed in the major concert halls of the city and has been pre- sentedAbout in its most important festivals. The orchestra’s unique and Chamber Philharmonic progressive programming has distinguished it from the many orches- tras of the city. It has performed over 130 works, including over has become an integral a dozen world premieres, introduced St. Petersburg audiences to more than 30 young performers, conductors and composers from part of the city’s culture” 15 different countries (such up-and-coming stars as Alisa Weilerstein, cello), and performed works by nearly 20 living American compos- ers, including Russian premieres of works by Pulitzer Prize-winning American composers Steve Riech, Steven Stucky and John Adams. Festival Appearances: Symphony Space, Wall-to-Wall Festival, “Behind the Wall”, 2010 “The orchestra 14th International Musical Olympus Festival, 2009 & 2010 International New Music Festival “Sound Ways”, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 demonstrates splendid 43rd International Festival St. Petersburg “Musical Spring”, 2006 5th Annual Festival “Japanese Spring in St. Petersburg”, 2005 virtuosity” “Avant-garde in our Days” Music Festival, 2003 Halls: Symphony Space, New York City Academic Capella Hall of Mirrors, Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace Hermitage Theatre “Magnificent” Maly Sal (Glinka) of the Philharmonic Shuvalovksy Palace Hall, Fontanka River St. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

DRJ 45 1 Bookreviews 118..139

under-represented in popular dance research. Hutchinson, Sydney. 2007. From Quebradita to Sunday Serenade is a weekly social dance geared Duranguense: Dance in Mexican American toward mature Caribbean British immigrants, Youth Culture. Tucson, AZ: University of predominantly from Jamaica. Dodds argues Arizona Press. that community at this event is created through Morris, Gay. 2009. “Dance Studies/Cultural inclusion (of multiple music genres, dance Studies.” Dance Research Journal 41(1): styles, and people from varying economic back- 82–100. grounds) as an antidote to the exclusion that Nájera-Ramírez, Olga, Norma E. Cantú, and many of these immigrants have experienced in Brenda M. Romero, eds. 2009. Dancing British society. Many questions arose for me Across Borders: Danzas y Bailes Mexicanos. that were not answered in this chapter—such Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. as how gender roles were played out at this Oliver, Cynthia. 2010. “Rigidigidim de Bamba dance. I suspect, however, that such outstanding de: A Calypso Journey from Start to ...” In questions were a sign of how well Dodds had Making Caribbean Dance: Continuity and nurtured my investment in this community Creativity in Island Cultures, edited by rather than an indication of any real shortcom- Susanna Sloat, 3–10. Gainesville, FL: ings in her scholarship. University Press of Florida. The larger questions that I found myself Savigliano, Marta Elena. 2009. “Worlding Dance pondering at the end of the book are issues I and Dancing Out There in the World.” In hope all dance ethnographers grapple with on Worlding Dance, edited by Susan Leigh Foster, an ongoing basis. In none of these case studies 163–90. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Baur 831792.Pdf (5.768Mb)

Ravel's "Russian" Period: Octatonicism in His Early Works, 1893-1908 Author(s): Steven Baur Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 531-592 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/831792 Accessed: 05-05-2016 18:10 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press, American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society This content downloaded from 129.173.74.49 on Thu, 05 May 2016 18:10:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Ravel's "Russian" Period: Octatonicism in His Early Works, 1893-1908 STEVEN BAUR The most significant writing on the octatonic scale in Western music has taken as a starting point the music of Igor Stravinsky. Arthur Berger introduced the term octatonic in his landmark 1963 article in which he identified the scale as a useful framework for analyzing much of Stravinsky's music. Following Berger, Pieter van den Toorn discussed in greater depth the nature of Stravinsky's octatonic practice, describing the composer's manipula- tions of the harmonic and melodic resources provided by the scale. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

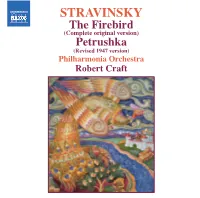

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

1. Charles Ives's Four Ragtime Dances and “True American Music”

37076_u01.qxd 3/21/08 5:35 PM Page 17 1. Charles Ives’s Four Ragtime Dances and “True American Music” Someone is quoted as saying that “ragtime is the true American music.” Anyone will admit that it is one of the many true, natural, and, nowadays, conventional means of expression. It is an idiom, perhaps a “set or series of colloquialisms,” similar to those that have added through centuries and through natural means some beauty to all languages. Ragtime has its possibilities. But it does not “represent the American nation” any more than some fine old senators represent it. Perhaps we know it now as an ore before it has been refined into a product. It may be one of nature’s ways of giving art raw material. Time will throw its vices away and weld its virtues into the fabric of our music. It has its uses, as the cruet on the boarding-house table has, but to make a meal of tomato ketchup and horse-radish, to plant a whole farm with sunflowers, even to put a sunflower into every bouquet, would be calling nature something worse than a politician. charles ives, Essays Before a Sonata Today, more than a century after its introduction, the music of ragtime is often regarded with nostalgia as a quaint, polite, antiquated music, but when it burst on the national scene in the late 1890s, its catchy melodies and en- ergetic rhythms sparked both delight and controversy. One of the many fruits of African American musical innovation, this style of popular music captivated the nation through the World War I era with its distinctive, syn- copated rhythms that enlivened solo piano music, arrangements for bands and orchestras, ballroom numbers, and countless popular songs.