Baur 831792.Pdf (5.768Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

Season 2016-2017

23 Season 2016-2017 Thursday, January 26, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 27, at 2:00 City of Light and Music: The Paris Festival, Week 3 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Choong-Jin Chang Viola Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16 I. Harold in the Mountains (Scenes of melancholy, happiness, and joy) II. Pilgrims’ March—Singing of the Evening Hymn III. Serenade of an Abruzzi Mountaineer to his Sweetheart IV. Brigands’ Orgy (Reminiscences of the preceding scenes) Intermission Ravel Alborada del gracioso Ravel Rapsodie espagnole I. Prelude to the Night— II. Malagueña III. Habanera IV. Feria Ravel Bolero This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. The January 26 concert is sponsored in memory of Ruth W. Williams. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit WRTI.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Steven Spielberg’s filmE.T. the Extra-Terrestrial has always held a special place in my heart, and I personally think it’s his masterpiece. In looking at it today, it’s as fresh and new as when it was made in 1982. Cars may change, along with hairstyles and clothes … but the performances, particularly by the children and by E.T. himself, are so honest, timeless, and true, that the film absolutely qualifies to be ranked as a classic. What’s particularly special about today’s concert is that we’ll hear one of our great symphony orchestras, The Philadelphia Orchestra, performing the entire score live, along with the complete picture, sound effects, and dialogue. -

A BIOGRAPHY of JOSEPH MAURICE RAVEL by Matthew Dechirico

A BIOGRAPHY OF JOSEPH MAURICE RAVEL by Matthew DeChirico Joseph Maurice Ravel, who lived from March 1875 to December 1937 was a French composer born in the Basque region of France His mother of Basque-Spanish heritage from Madrid Spain had a strong influence on his life and his music. His father was a Swiss inventor and industrialist from France. Both parents provided a happy and stimulating life for Joseph and his younger brother. His parents encouraged his musical pursuits and sent him at age 14 to the Conservatoire de Paris first as a preparatory student and eventually as a piano major. Although intellectually bright and well read, he was not successful academically even as his musicianship matured. Considered “very gifted” he nevertheless was called “somewhat heedless” in his studies. He failed to meet the requirements of earning a competitive medal and was expelled. He returned three years later studying with Gabriel Faure focusing on composition rather than piano. He was again dismissed for having won neither the fugue nor the composition prize. He remained an auditor with Faure until he left the Conservatoire in 1903. During his years at the Conservatoire, Ravel tried numerous times to win the prestigious Prix de Rome but to no avail: he was probably considered too radical by the conservatives. Ravel’s “String Quartet in F” is now a standard work of chamber music, though at the time it was criticized and found lacking academically. His first significant work, “Habanera” for two pianos was later transcribed into the third movement of his “Rapsodie Espagnole”. -

(MTO 21.1: Stankis, Ravel's ficolor

Volume 21, Number 1, March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory Maurice Ravel’s “Color Counterpoint” through the Perspective of Japonisme * Jessica E. Stankis NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.15.21.1/mto.15.21.1.stankis.php KEYWORDS: Ravel, texture, color, counterpoint, Japonisme, style japonais, ornament, miniaturism, primary nature, secondary nature ABSTRACT: This article establishes a link between Ravel’s musical textures and the phenomenon of Japonisme. Since the pairing of Ravel and Japonisme is far from obvious, I develop a series of analytical tools that conceptualize an aesthetic orientation called “color counterpoint,” inspired by Ravel’s fascination with Chinese and Japanese art and calligraphy. These tools are then applied to selected textures in Ravel’s “Habanera,” and “Le grillon” (from Histoires naturelles ), and are related to the opening measures of Jeux d’eau and the Sonata for Violin and Cello . Visual and literary Japonisme in France serve as a graphical and historical foundation to illuminate how Ravel’s color counterpoint may have been shaped by East Asian visual imagery. Received August 2014 1. Introduction It’s been given to [Ravel] to bring color back into French music. At first he was taken for an impressionist. For a while he encountered opposition. Not a lot, and not for long. And once he got started, what production! —Léon-Paul Fargue, 1920s (quoted in Beucler 1954 , 53) Don’t you think that it slightly resembles the gardens of Versailles, as well as a Japanese garden? —Ravel describing his Le Belvédère, 1931 (quoted in Orenstein 1990 , 475) In “Japanizing” his garden, Ravel made unusual choices, like his harmonies. -

Ravel, Maurice (1875-1937) by John Louis Digaetani

Ravel, Maurice (1875-1937) by John Louis DiGaetani Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright ©2002, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Maurice Ravel in 1915. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and One of France's most distinguished composers, Maurice Ravel was a prolific and Photographs Division. versatile artist who worked in several musical genres, creating stage music (two operas and several ballets), orchestral music, vocal music, chamber music, and piano music. His unique musical language, employing harmonies that are at once ravishing and subtle, made him one of the most influential composers of the twentieth century. Ravel's sexuality has been the subject of intense speculation. Although it is not certain that he was gay, he was rumored to be so. Fiercely protective of his privacy, his most significant emotional relationship seems to have been with his mother. At the same time, however, he embraced a public identity as a cultured dandy, a dapper man-about-town of refined taste and sensibility. A life-long bachelor, Ravel had several significant relationships with men, including one with pianist Ricardo Viñes, a fellow dandy and bachelor, but it is not certain whether these friendships were sexual. He was born Joseph Maurice Ravel on March 7, 1875 at Ciboure, France, near St. Jean de Luz, Basses- Pyrénées, a village close to the French-Spanish border, to a Swiss father and a Basque mother. Ravel's father, who was talented musically, was an engineer. The composer may have inherited from his father the devotion to craftsmanship and meticulous detail that led Igor Stravinsky to describe him as the "Swiss watch-maker of music." Although he was raised in Paris, Ravel was very conscious of his Basque heritage. -

Modern French Composers: I. How They Are Encouraged Author(S): M

Modern French Composers: I. How They Are Encouraged Author(s): M. D. Calvocoressi Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 62, No. 938 (Apr. 1, 1921), pp. 238-240 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/909393 Accessed: 04-11-2015 08:30 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.237.29.138 on Wed, 04 Nov 2015 08:30:43 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 238 THE MUSICAL TIMES-APRIL I 1921I Ex. 5. I , opinion of posterity,it is not unlikelythat most of us would be overwhelmed with surprise- - - as most of Kiss me and take my sol in exactly Beethoven's contemporaries . would have been had theyknown what his ultimate standingwould be. Even withoutattempting to deliverjudgment as to the comparativemerits of the modern French school, there is one statementthat can unhesi- tatinglybe made: of all countries that have constantlytaken an interestin music, none has rit. hoco oPP duringthe past hundred yearsor so made greater headway than France. -

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’S Neoclassical Keyboard Works

Toward a Theory of Formal Function in Stravinsky’s Neoclassical Keyboard Works Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Mueller, Peter M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 03:29:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/626657 TOWARD A THEORY OF FORMAL FUNCTION IN STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICAL KEYBOARD WORKS by Peter M. Mueller __________________________ Copyright © Peter M. Mueller 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

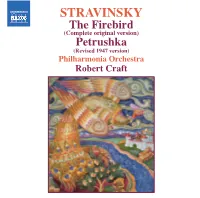

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

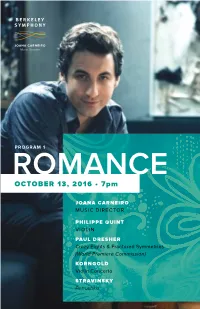

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

Dictionary of Music.Pdf

The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music Christine Ammer The Facts On File Dictionary of Music, Fourth Edition Copyright © 2004 by the Christine Ammer 1992 Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ammer, Christine The Facts On File dictionary of music / Christine Ammer.—4th ed. p. cm. Includes index. Rev. ed. of: The HarperCollins dictionary of music. 3rd ed. c1995. ISBN 0-8160-5266-2 (Facts On File : alk paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3009-5 (e-book) 1. Music—Dictionaries. 2. Music—Bio-bibliography. I. Title: Dictionary of music. II. Ammer, Christine. HarperCollins dictionary of music. III. Facts On File, Inc. IV. Title. ML100.A48 2004 780'.3—dc22 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by James Scotto-Lavino Cover design by Semadar Megged Illustrations by Carmela M. Ciampa and Kenneth L. Donlan Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise.” Copyright © 1960 Hinrichsen Edition, Peters Edition Limited, London.