Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1) Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient and ___

5 16. (50) If a 14th-century composer wrote a mass. what would be the names of the movement? TQ: Why? Chapter 3 Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei. The text remains Roman Liturgy and Chant the same for each day throughout the year. 1. (47) Define church calendar. 17. (51) What is the collective title of the eight church Cycle of events, saints for the entire year services different than the Mass? Offices [Hours or Canonical Hours or Divine Offices] 2. TQ: What is the beginning of the church year? Advent (four Sundays before Christmas) 18. Name them in order and their approximate time. (See [Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, 46 days before Easter] Figure 3.3) Matins, before sunrise; Lauds, sunrise; Prime, 6 am; Terce, 9 3. Most important in the Roman church is the ______. am; Sext, noon; Nones, 3 pm; Vespers, sunset; Mass Compline, after Vespers 4. TQ: What does Roman church mean? 19. TQ: What do you suppose the function of an antiphon is? Catholic Church To frame the psalm 5. How often is it performed? 20. What is the proper term for a biblical reading? What is a Daily responsory? Lesson; musical response to a Biblical reading 6. (48) Music in Context. When would a Gloria be omitted? Advent, Lent, [Requiem] 21. What is a canticle? Poetic passage from Bible other than the Psalms 7. Latin is the language of the Church. The Kyrie is _____. Greek 22. How long does it take to cycle through the 150 Psalms in the Offices? 8. When would a Tract be performed? Less than a week Lent 23. -

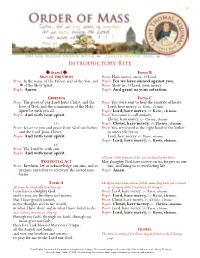

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite At

Mass in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite A Solemn High Mass celebrated in the Extraordinary Form of the Mass of the Roman Rite (according to the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal) is scheduled for Sacred Heart Cathedral on Sunday, September 15, 2019, 3:00 pm. Fr. Daniel Geddes from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, Pastor of Holy Family Parish in Vancouver, will be the celebrant. As a simple explanation, in 2007 Pope Benedict XVI issued a document entitled “Summorum Pontificum” which gave priests anywhere around the world permission to celebrate the Mass using the 1962 Missal. In his letter to bishops concerning the document, he explained that the liturgical tradition of the Roman Rite incorporated two forms – the ordinary, which we celebrate regularly, and the extraordinary, to which many have continued to be devoted. Both forms belong to the Roman Rite and are to be seen as the continual flow of the 2000-year liturgical tradition of the Church. The pope emphasized there was no fracture of the tradition at the Second Vatican Council. Both forms are celebrated in Latin, although the current edition of the Roman Missal allows for vernacular languages to be used. The Apostolic Letter, Summorom Pontificum was issued on July 7, 2007 and carried an effective date of September 14, 2007. Hence, 12 years after the letter’s effective date, Mass will again be offered at Sacred Heart Cathedral in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite. Members of the UnaVoce Prince George Chapter will be providing servers and a schola (choir). -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

The Penitential Rite & Kyrie

The Mass In Slow Motion Volumes — 7 and 8 The Penitential Rite & The Kyrie The Mass In Slow Motion is a series on the Mass explaining the meaning and history of what we do each Sunday. This series of flyers is an attempt to add insight and understanding to our celebration of the Sacred Liturgy. You are also invited to learn more by attending Sunday School classes for adults which take place in the school cafeteria each Sunday from 9:45 am. to 10:45 am. This series will follow the Mass in order. The Penitential Rite in general—Let us recall that we have just acknowledged and celebrated the presence of Christ among us. First we welcomed him as he walked the aisle of our Church, represented by the Priest Celebrant. The altar, another sign and symbol of Christ was then reverenced. Coming to the chair, a symbol of a share in the teaching and governing authority of Christ, the priest then announced the presence of Christ among us in the liturgical greeting. Now, in the Bible, whenever there was a direct experience of God, there was almost always an experience of unworthiness, and even a falling to the ground! Isaiah lamented his sinfulness and needed to be reassured by the angel (Is 6:5). Ezekiel fell to his face before God (Ez. 2:1). Daniel experienced anguish and terror (Dan 7:15). Job was silenced before God and repented (42:6); John the Apostle fell to his face before the glorified and ascended Jesus (Rev 1:17). Further, the Book of Hebrews says that we must strive for the holiness without which none shall see the Lord (Heb. -

Opening Bell Toll Creed of Prayer on Final Page Psalm 25 Kyrie

Opening Psalm 25 Bell Toll Kyrie Creed of Prayer on final page Preparation Communion Closing Bell Toll Nicene Creed Apostles’ Creed I believe in one God, I believe in God, the Father almighty, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, Creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, All bow at the following words up to: the Virgin Mary. I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Virgin Mary, born of the Father before all ages. suffered under Pontius Pilate, God from God, Light from Light, was crucified, died and was buried; true God from true God, he descended into hell; begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; on the third day he rose again from the dead; through him all things were made. he ascended into heaven, For us men and for our salvation and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; he came down from heaven, All bow at the following words up to: and became man. from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, I believe in the Holy Spirit, and became man. the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, the forgiveness of sins, he suffered death and was buried, the resurrection of the body, and rose again on the third day and life everlasting. -

The Agnus Dei

New and Corrected Translation of the Mass – Part 26 The Agnus Dei Lamb of God, Gen 22.8; Ex 12; 1 Cor 5.7 you take away the sins of the world, Lev 16.21; Jn 1.29 have mercy on us. Lamb of God, 1 Pet 1.19; Rev 5.6 you take away the sins of the world, 1 Jn 2.2 have mercy on us Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, grant us peace. John 14.27; 20.26 Immediately after the Pax, the priest begins the Fraction, i.e. breaking the Host, which shows the death of Jesus, whose body was broken for us in the Sacrifice of the Cross (although not one of His bones was broken, cf. John 19.36). The priest takes a small particle of the Host and adds it to the Precious Blood in the chalice. This act, called the ‘commingling’, signifies the Resurrection, the coming together again of Christ’s Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity (even in death His Divinity remained united to all three preceding, which are part of His humanity). The Agnus Dei is a chant which accompanies the Fraction. Everyone says or sings it, using the words of St John the Baptist to point out Jesus as the Messiah. In the Eastern churches the sacrificial gifts are called “the Lamb”. It is the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist that moves us to call Jesus ‘Lamb of God’ at this point of the Mass, cf. “I saw a Lamb standing, as it were slain” (Rev 5.6). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12Th Century, Paris, Bibl

SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1, Spring 1972 Cistercian Gradual (12th century, Paris, Bibl. Nat., ms . lat. 17,328) SACRED MUSIC Volume 99, Number 1 , Spring 1972 BERNSTEIN'S MASS 3 Herman Berlinski TU FELIX AUSTRIA 9 Reverend Robert Skeris MUSICAL SUPPLEMENT 13 REVIEWS 20 FROM THE EDITOR 25 NEWS 26 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caeci/ia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publication: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minne sota 55103. Editorial office: Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062. Editorial Board Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Editor Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J. Rev. Lawrence Heiman, C.PP.S. J. Vincent Higginson Rev. Peter D. Nugent Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler Frank D. Szynskie Editorial correspondence: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist., Route 2, Box I, Irving, Texas 75062 News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J., Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase, New York 10577 Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil 3257 South Lake Drive Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53207 Membership and Circulation: Frank D. Szynskie, Boys Town, Nebraska 68010 AdvertisinR: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist. CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Dr. Roger Wagner Vice-president Noel Goemanne General Secretary Rev. Robert A. Skeris Treasurer Frank D. Szynskie Directors Robert I. -

The Credo the Rt

The Diocese of the Mid-Atlantic States Of the Anglican Catholic Church The credo The Rt. Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Managing Editor The Rev’d Fr. T.L. Crowder, Content Editor Saint Aidan, Bishop and Confessor 31 August, A.D. 2015 The Crozier The Right Rev’d D. Francis Lerow, Bishop Ordinary Missions and Decisions, Planning and Money For many of our parishes, renewal tends to be an ongoing affair. We think very hard about our home parish. All of us want our church to have impact on the community and our community to have greater access to worship and the Traditional Anglican way. We depend on our vestries to drive the wagon that ensures that proper planning and resources are available to support the annual plan established at the Annual Parish Meetings. The problem with planning is that it quickly can lose the interest of the members of the parish. It is easy to fall back into our old ways, thinking that the Sunday Worship Service is all we need to bring them to Christ and eventually membership in the Church. Or if we have a young electrifying priest that will lead the way all will be well. It would be nice if it was that easy. But, we all know it is not. So what does it take? What kind of investment of time and resources does it take to really make things happen? What will cause the kind of renewal for which we all hope and pray? The business metric used to determine the effort and cost to sell a particular item of merchandise, as a rule of thumb, is to measure how many times their product gets the attention of a potential buyer. -

Liturgy and Music Planning Overview Use This Page to Help You Navigate the Planning Sheets Available for Every Sunday’S Masses in the Hall Chapels

Liturgy and Music Planning Overview Use this page to help you navigate the planning sheets available for every Sunday’s Masses in the hall chapels. Black text will be found every week on the weekly planning sheets. Everything in red represents information pertinent to using the planning sheets and planning your liturgies. Date: Here, the calendar date for the upcoming Sunday. For example, “August 24, 2014.” Which is the … this line will show you which week of which season and year we celebrate. For example, “21st Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year A” Lectionary # In the Lectionary (the book of Sunday readings) every week’s readings are noted by a number. This is not a page number, but is found at the top of the page at the beginning of each new week’s readings. The weekday lectionaries also use these numbers as well. Readings ‐‐ here you will find the readings for each Sunday listed. You can link to the readings online at usccb.org. Click on the calendar icon for the Sunday (or weekday) for the readings you want to find. I: II: G: Themes/To reflect on and think about: ‐‐ here several themes that run through the readings will be listed. You may also find a question or reflection or two to think or talk about. Planning your music … Now we can start choosing music for the Mass! Begin with the Mass setting, which should stay the same for the whole season (meaning Church season, not the weather!). During the Fall semester, we are in Ordinary Time until Advent, which in 2014 begins on November 30. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev.