Doctor of Musical Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

STRAVINSKY's NEO-CLASSICISM and HIS WRITING for the VIOLIN in SUITE ITALIENNE and DUO CONCERTANT by ©2016 Olivia Needham Subm

STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT By ©2016 Olivia Needham Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird ________________________________________ Véronique Mathieu ________________________________________ Bryan Haaheim ________________________________________ Philip Kramp ________________________________________ Jerel Hilding Date Defended: 04/15/2016 The Dissertation Committee for Olivia Needham certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: STRAVINSKY’S NEO-CLASSICISM AND HIS WRITING FOR THE VIOLIN IN SUITE ITALIENNE AND DUO CONCERTANT ________________________________________ Chairperson: Paul Laird Date Approved: 04/15/2016 ii ABSTRACT This document is about Stravinsky and his violin writing during his neoclassical period, 1920-1951. Stravinsky is one of the most important neo-classical composers of the twentieth century. The purpose of this document is to examine how Stravinsky upholds his neoclassical aesthetic in his violin writing through his two pieces, Suite italienne and Duo Concertant. In these works, Stravinsky’s use of neoclassicism is revealed in two opposite ways. In Suite Italienne, Stravinsky based the composition upon actual music from the eighteenth century. In Duo Concertant, Stravinsky followed the stylistic features of the eighteenth century without parodying actual music from that era. Important types of violin writing are described in these two works by Stravinsky, which are then compared with examples of eighteenth-century violin writing. iii Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov) in Russia near St. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

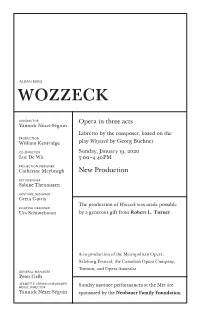

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Saturday, April 18, 2015 8 p.m. 7:15 p.m. – Pre-performance discussion Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts www.quickcenter.com ~INTERMISSION~ COPLAND ................................ Two Pieces for Violin and Piano (1926) K. LEE, MCDERMOTT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, piano STRAVINSKY ................................Concertino for String Quartet (1920) DAVID SHIFRIN, clarinet AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, KRISTIN LEE, violin SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA AMPHION STRING QUARTET KATIE HYUN, violin DAVID SOUTHORN, violin COPLAND ............................................Sextet for Clarinet, Two Violins, WEI-YANG ANDY LIN, viola Viola, Cello, and Piano (1937) MIHAI MARICA, cello Allegro vivace Lento Finale STRAVINSKY ..................................... Suite italienne for Cello and Piano SHIFRIN, HYUN, SOUTHORN, Introduzione: Allegro moderato LIN, MARICA, MCDERMOTT Serenata: Larghetto Aria: Allegro alla breve Tarantella: Vivace Please turn off cell phones, beepers, and other electronic devices. Menuetto e Finale Photographing, sound recording, or videotaping this performance is prohibited. MARICA, MCDERMOTT COPLAND ...............................Two Pieces for String Quartet (1923-28) AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA STRAVINSKY ............................Suite from Histoire du soldat for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano (1918-19) The Soldier’s March Music to Scene I Music to Scene II Tonight’s performance is sponsored, in part, by: The Royal March The Little Concert Three Dances: Tango–Waltz–Ragtime The Devil’s Dance Great Choral Triumphal March of the Devil K. LEE, SHIFRIN, MCDERMOTT Notes on the Program by DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Two Pieces for String Quartet Aaron Copland Suite italienne for Cello and Piano Born November 14, 1900 in Brooklyn, New York. Igor Stravinsky Died December 2, 1990 in North Tarrytown, New York. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1947 Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947)." , (1947). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/181 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. XUQfr JNftr o 10 I s vation Army Band, has retired, after an AARON COPLAND’S Third Symphony unbroken record of sixty-four years’ serv- and Ernest Bloch’s Second Quartet have ice as Bandmaster in the Salvation Army. won the Award of the Music Critics Cir- cle of New York as the outstanding music American orchestral and chamber THE SALZBURG FESTI- BEGINNERS heard for the first time in New York VAL, which opened on PIANO during the past season. YOUNG July 31, witnessed an im- FOB portant break with tra- JOHN ALDEN CARPEN- dition when on August TER, widely known con- 6 the world premiere of KEYBOARD TOWN temporary American Gottfried von Einem’s composer, has been opera, “Danton’s Tod,” By Louise Robyn awarded the 1947 Gold was produced. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

PIANO KAPUSTIN: a Recap of Recent Classical Releases

HAL LEONARD WIN T ER 2019 UPDATE NIKOLAI Within this newsletter you will find PIANO KAPUSTIN: a recap of recent classical releases. HUMORESQUE, The following classical catalogs are JOHANN SEBASTIAN OP. 75 distributed by Hal Leonard: BACH/JOHANNES Schott BRAHMS: CHACONNE The Humoresque Op. 75 Alphonse Leduc FROM PARTITA NO. 2 IN D — composed in 1994 — is Associated Music MINOR considered one of the most Publishers ARRANGEMENT FOR PIANO, difficult pieces by Kapustin. Boosey & Hawkes LEFT-HAND Presented in the standard jazz Bosworth Music form, the variations sound like Henle Urtext Edition Bote & Bock The D-minor Chaconne is improvisations, influenced by undoubtedly the most famous McCoy Tyner’s style, but are minutely through-composed. Chester Music movement of all of Bach’s 6 49046035 ......................................................................$16.99 DSCH Sonatas and Partitas for violin. Editio Musica Budapest So it is hardly surprising that it has seen many arrangements. Editions Durand Johannes Brahms marvelled at how a single staff of music could SERGEI RACHMANINOFF: offer “a whole world of the deepest thoughts and the mightiest PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN Editions Max Eschig emotions.” He promptly made his own arrangement for piano, B-FLAT MINOR, OP. 36 Editions Musicales left hand alone. 1913 & 1931 VERSIONS Transatlantique 51481187 ........................................................................$11.95 ed. Dominik Rahmer, fing. Editions Salabert Marc-André Hamelin Ediciones Henle Urtext Edition Joaquín Rodrigo FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: Includes both Rachmaninoff’s Edward B. Marks SCHERZI original 1913 version and Music Company ed. Norbert Müllemann edited 1931 version of this Eulenburg fing. Hans-Martin Theopold substantial piece, with Forberg Henle Urtext Edition fingerings by Marc-André 51480886 ........................$25.95 Hamelin.