Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

Ballet? Y First the Ballerina Glides Across the Stage, Her Arms M Making Lovely Lines in the Air

My First alle B Album t What is Ballet? Firs The ballerina glides across the stage, her arms My t making lovely lines in the air. A beautiful tune comes from the strings of the large orchestra. She is the Sleeping Beauty: she was put into a allet deep magic sleep by the wicked witch. But she B lbum has now been woken by her handsome prince, A and he dances joyfully with her, athletic and strong. Another time, she is Princess Odette from Swan Lake, and around her the other dancers – swans in white chiffon – weave patterns in time to the music. And yet another time, she is the Sugar Plum Fairy celebrating the joy of Christmas in The Nutcracker. This is ballet, the classical dance that, once seen, is never forgotten. Even though today we have film and video games, ballet is still a powerful vision of beauty and excitement. The dancers use the strength of an athlete, the balance of a gymnast and the sensitivity of a violinist to tell stories through their dancing. Here is some of the best music which has propelled dancers for hundreds of years. 2 Tchaikovsky Swan Lake Stravinsky The Firebird 1 Scene 2:37 3 Scene I. The Firebird’s Dance 1:19 Keyword: Oboe Keyword: Fire Swan Lake is a ballet from Russia about a prince called Siegfried. In the forest he finds A firebird is a brightly coloured magical bird that comes a mysterious lake where swans are swimming, led by a beautiful but sad swan wearing out of the fire. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 FIFTY—NINTH SEASON, 1939-194o CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD BURGIN, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by JOHN N. BURK COPYRIGHT, 1939, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. ERNEST B. DANE • • President HENRY B. SAWYER Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . • Treasurer HENRY B. CABOT M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE ERNEST B. DANE ROGER I. LEE ALVAN T. FULLER RICHARD C. PAINE JEROME D. GREENE HENRY B. SAWYER N. PENROSE HALT OWELL EDWARD A. TAFT BENTLEY W. WARREN G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager ( 289 ) Complete FIDUCIARY SERVICE /^INDIVIDUALS The fiduciary services of Old Colony Trust Company available to individuals are many and varied. We cite some of the fiduciary capacities in which we act. Executor and Administrator We settle estates as Executor and Administrator. Trustee We act as Trustee under wills and under voluntary or living trusts. Agent We act as Agent for those who wish to be relieved of the care of their investments. The officers of Old Colony Trust Company are always glad to discuss estate and property matters with you and point out if and where our services are applicable. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON Member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation ^Allied w/'MThe First National Bank ^Boston [ 290] ,1 FIFTY-NINTH SEASON - NINETEEN HUNDRED THIRTY-NINE AND FORTY Seventh Programme FRIDAY AFTERNOON, December i, at 2:30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, December 2, at 8:15 o'clock IGOR STRAVINSKY Conducting Stravinsky "Jeu de Cartes" (Card Game, Ballet in Three Deals) (First performances at these concerts) Stravinsky Capriccio for Orchestra with Piano Solo I. -

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky Source: http://www.8notes.com/biographies/stravinsky.asp ‘Even during his lifetime, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a legendary figure. His once revolutionary work were modern classics, and he influenced three generations of composers and other artists. Cultural giants like Picasso and T. S. Eliot were his friends. President John F. Kennedy honored him at a White House dinner in his eightieth year. 'Stavinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, near St. Petersburg (Leningrad), grew up in a musical atmosphere, and studied with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He had his first important opportunity in 1909, when the impresario Sergei Diaghilev heard his music. Diaghilev was the director of the Russian Ballet, an extremely influential troupe which employed great painters as well as important dances, choreographers, and composers. Diaghilev first asked Stravinsky to orchestrate some piano pieces by Chopin as ballet music and then, in 1910, commissioned an original ballet, The Firebird, which was immensely successful. A year later (1911), Stravinsky's second ballet, Petrushka, was performed, and Stravinsky was hailed as a modern master. When his third ballet, The Rite of Spring (a savage, brutal portrayal of a prehistoric ritual in which a young girl is sacrificed to the god of Spring.), had its premiere in Paris in 1913, a riot erupted in the audience--spectators were shocked and outraged by its pagan primitivism, harsh dissonance, percussiveness, and pounding rhythms--but it too was recognized as a masterpiece and influenced composers all over the world. 'During World War I, Stravinsky sought refuge in Switzerland; after the armistice, he moved to France, his home until the onset of World War II, when he came to the United States. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Influence of Commedia Dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟S Suite Italienne D.M.A

Influence of Commedia dell‟Arte on Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi, B.M., M.A., M.B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Document Committee: Kia-Hui Tan, Advisor Paul Robinson Mark Rudoff Copyright by Sachiho Cynthia Murasugi 2009 Abstract Suite Italienne for violin and piano (1934) by Stravinsky is a compelling and dynamic work that is heard in recitals and on recordings. It is based on Stravinsky‟s music for Pulcinella (1920), a ballet named after a 16th century Neapolitan stock character. The purpose of this document is to examine, through the discussion of the history and characteristics of Commedia dell‟Arte ways in which this theatre genre influenced Stravinsky‟s choice of music and compositional techniques when writing Pulcinella and Suite Italienne. In conclusion the document proposes ways in which the violinist can incorporate the elements of Commedia dell‟Arte that Stravinsky utilizes in order to give a convincing and stylistic performance. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Kia-Hui Tan and my committee members, Dr. Paul Robinson, Prof. Mark Rudoff, and Dr. Jon Woods. I also would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of my first advisor, the late Prof. Michael Davis. iii Vita 1986………………………………………….B.M., Manhattan School of Music 1988-1989……………………………….…..Visiting International Student, Utrecht Conservatorium 1994………………………………………….M.A., CUNY, Queens College 1994-1995……………………………………NEA Rural Residency Grant 1995-1996……………………………………Section violin, Louisiana Philharmonic 1998………………………………………….M.B.A., Tulane University 1998-2008……………………………………Part-time instructor, freelance violinist 2001………………………………………….Nebraska Arts Council Touring Artists Roster 2008 to present………………………………Lecturer in Music, Salisbury University Publications “Stravinsky‟s Suite Italienne Unmasked.” Stringendo 25.4 (2009):19. -

Stravinsky - Les Noces, Renard, Ragtime for Eleven Instruments - the Audio Beat - 15.02.17, 17�05

Stravinsky - Les Noces, Renard, Ragtime for Eleven Instruments - The Audio Beat - www.TheAudioBeat.com 15.02.17, 1705 Music Reviews Stravinsky • Les Noces, Renard, Ragtime for Eleven Instruments Columbia/Speakers Corner MS6372 180-gram LP 1959/2016 Music Sound by Mark Blackmore | February 15, 2017 gor Stravinsky began preliminary sketches for Les Noces as early as 1912, but he was busy working on The Rite of Spring and wouldn't complete the final score until 1923. It was based on folk themes and poetry, and Stravinsky would describe the ballet as a collection of "cliches and quotations of typical Russian wedding sayings." As you read the libretto, the same phrases keep repeating, much like hearing snippets of conversation from many people discussing and preparing for the wedding. If you are familiar with Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, then Les Noces will seem familiar, but certainly less melodic. Orff admitted being influenced by hearing Les Noces and modeled much of Carmina on Stravinsky's work. Stravinsky had considered a huge orchestra for Les Noces but settled on the final orchestration of four soloists, four pianos, chorus and six percussionists. This choice of a smaller ensemble meant it could never be a sonic tour de force like his Rite or Firebird. Dedicated to Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballet Russes, Les Noces was first performed in 1923 by that ensemble and conducted by Ernest Ansermet. This reissue is of the 1959 Columbia recording, which has great star power: Stravinsky conducting and the four piano parts played by Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, Lukas Foss and Roger Sessions, each a leading American composer. -

Igor Stravinsky's “Symphony of Psalms” – a Testimony of the Composer's Faith

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 9 (58) No. 2 - 2016 Igor Stravinsky’s “Symphony of Psalms” – a testimony of the composer’s faith Petruţa-Maria COROIU 1, Alexandra BELIBOU2 Abstract: In the musical landscape of the first half of the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky (1882- 1971) asserted himself as a musician who undermined the normative values of the elements in the musical discourse. His creations were regarded from an analytical perspective in opposition with Arnold Schonberg’s music, the musical critics trying to limit the compositional amendments of the 20th century to the scores of the two composers. We find this view unjust, the musical wealth of the 20th century stemming precisely from the multiple meanings framed within various compositional patterns by the composers which music history placed among the unforgettable ones. Key-words: faith, modernity, psalm, composition, style 1. Preliminary considerations In the musical landscape of the first half of the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky (1882- 1971) asserted himself as a musician who undermined the normative values of the elements in the musical discourse. His creations were regarded from an analytical perspective in opposition with Arnold Schonberg’s music, the musical critics trying to limit the compositional amendments of the 20th century to the scores of the two composers. We find this view unjust, the musical wealth of the 20th century stemming precisely from the multiple meanings framed within various compositional patterns by the composers which music history placed among the unforgettable ones. It is worth noting that Stravinsky and Schonberg “constitute the poles towards gravitate the tendencies of the other composers of the century” (Vlad 1967, 7) (our translation). -

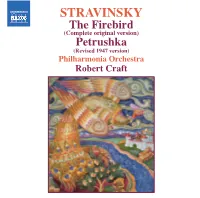

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire. -

Let's Play Bassoon

LET’S PLAY Bassoon By Hugo Fox Hugo Fox From 1922 until 1949, Hugo Fox served as principal bassoonist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, where he acquired an almost legendary reputation as one of the outstanding bassoonists of his era. During fifteen years of this period, he was instructor of bassoon at Northwestern University, and many of his students became ranked among the prominent bassoonists of America. During this period, his studies of the acoustics of the instrument and a desire to experiment, prompted him to form the Fox Bassoon Company, which now produces the well-known instru- ments that bear his name. 2 INTRODUCTION: This booklet has been prepared for the bandmaster or woodwind instructor who teaches the instrument, while not being an accomplished bassoonist. It is intended to serve as a handy reminder of some of the more important points to consider when starting a student, maintaining the instrument, and finishing reeds or reed blanks. The fingering chart is based on competent professional practices, and while not extensive in its treatment of alternate fingerings, is sufficiently complete to be used with almost any properly constructed instrument. 3 INDEX Introduction ....................................................................2-3 Starting the Student on Bassoon .................................... 5 Assembly of the Bassoon ...............................................6-7 Care of the Instrument ...................................................8-9 The Reed.....................................................................10-11 Fingering Charts .........................................................12-22 4 STARTING THE STUDENT ON THE BASSOON Either transfer the students from another instrument, or bassoon, much like when playing trombone. The air start them directly on bassoon. If you have access to a stream must have a clear, unobstructed path through the short-reach model bassoon, it is practical to start them in reed, continuing through the instrument.