Translating the Musical Language of Stravinsky's Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President

The Curtis Institute of Music Roberto Díaz, President This concert will be available online for free streaming 2008–09 Student Recital Series and download on Thursday, February 19. The Edith L. and Robert Prostkoff Memorial Concert Series Visit www.instantencore.com/curtis after 12 noon and enter this download code in the upper-right corner of the webpage: Feb09CTour Forty-Fourth Student Recital: Curtis On Tour Click “Go” and follow the instructions on the screen to save music Wednesday, February 18 at 8 p.m. Field Concert Hall onto your computer. Divertimento for Violin and Piano Igor Stravinsky Next Student Recital Sinfonia (1882–1971) Friday, February 20 at 8 p.m. Danses suisses 20/21: The Curtis Contemporary Music Ensemble— Scherzo Second Viennese School, Program III Pas de deux: Adagio—Variation—Coda Field Concert Hall Josef Špaček, violin Kuok-man Lio, piano Berg Sieben frühe Lieder Amanda Majeski, soprano Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo Stravinsky Mikael Eliasen, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet String Quartet, Op. 3 From the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám David Ludwig Joel Link, violin (world premiere) (b. 1972) Bryan A. Lee, violin Secrets of Creation Milena Pajaro-van de Stadt, viola Turning of Time Camden Shaw, cello Labor of Life Floating Particles Schoenberg Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 Carpe Diem Charlotte Dobbs, soprano Allison Sanders, mezzo-soprano David Moody, piano Yao Guang Zhai, clarinet William Short, bassoon Phantasy, Op. 47 Christopher Stingle, trumpet Elizabeth Fayette, violin Ryan Seay, trombone Pallavi Mahidhara, piano Benjamin Folk, percussion Josef Špaček, violin Programs are subject to change. Harold Hall Robinson, double bass Call the Recital Hotline, 215-893-5261, for the most up-to-date information. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

September 1, 2018

September 1, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed; a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Wagner Prelude to Act 1 ~ Parsifal Royal Concertgebouw/Haitink Philips 420 886 028942088627 00:14 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Don Juan, Op. 20 (Symphonic Poem) Pittsburgh Symphony/Honeck Reference Recordings 707 030911270728 00:33 Buy Now! Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. 114 Schmidl/Dolezal/Schiff London 410 114 028941011428 01:01 Buy Now! Pachelbel Suite in B flat for Strings Paillard Chamber Orchestra/Paillard Erato 98475 745099847524 01:13 Buy Now! Lalo Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21 Mutter/French National Orchestra/Ozawa EMI 547318 n/a 01:48 Buy Now! Geminiani Concerto No. 9 in A I Musici Philips 438 766 028943876629 02:01 Buy Now! Schumann Manfred Overture, Op. 115 Royal Concertgebouw/Haitink Philips 411 104 028941110428 Czecho-Slovak Radio 02:14 Buy Now! Humperdinck Prelude ~ The Canteen Woman Marco Polo 8.223369 4891030233630 Symphony/Fischer-Dieskau 02:23 Buy Now! Nicolai Symphony No. 2 in D Bamberg Symphony/Rickenbacher Virgin 91079 075679107923 03:00 Buy Now! Chopin Two Waltzes, Op. 18 & Op. 34 No. 1 Vladimir Ashkenazy London 414 600 028941460028 03:11 Buy Now! Reicha Horn Quintet in E, Op. 106 Klanska/Panocha Quartet Supraphon 73081 081757308120 03:40 Buy Now! Brahms Violin Sonata No. 2 in A, Op. 100 Perlman/Barenboim Sony 45819 07464458192 04:00 Buy Now! Bach Trio Sonata in G, BWV 1039 Florilegium Channel Classics 14598 723385145981 04:13 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

Leonide Massine: Choreographic Genius with A

LEONIDE MASSINE: CHOREOGRAPHIC GENIUS WITH A COLLABORATIVE SPIRIT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DANCE COLLEGE OF HEALTH, PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND RECREATION BY ©LISA ANN FUSILLO, D.R.B.S., B.S., M.A. DENTON, TEXAS Ml~.Y 1982 f • " /, . 'f "\ . .;) ;·._, .._.. •. ..._l./' lEXAS WUIVIAI'l' S UNIVERSITY LIBRAR't dedicated to the memories of L.M. and M.H.F. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express her appreciation to the members of her committee for their guidance and assistance: Dr. Aileene Lockhart, Chairman; Dr. Rosann Cox, Mrs. Adrienne Fisk, Dr. Jane Matt and Mrs. Lanelle Stevenson. Many thanks to the following people for their moral support, valuable help, and patience during this project: Lorna Bruya, Jill Chown, Mary Otis Clark, Leslie Getz, Sandy Hobbs, R. M., Judy Nall, Deb Ritchey, Ann Shea, R. F. s., and Kathy Treadway; also Dr. Warren Casey, Lynda Davis, Mr. H. Lejins, my family and the two o'clock ballet class at T.C.U. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION • • • . iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . iv LIST OF TABLES • . viii LIST OF FIGURES . ix LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . X Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Purpose • • • • • • • . • • • • 5 Problem • • . • • • • • . • • • 5 Rationale for the Study • • • . • . • • • • 5 Limitations of the Study • • . • • • • • 8 Definition.of Terms • . • • . • . • • 8 General Dance Vocabulary • • . • • . • • 8 Choreographic Terms • • • • . 10 Procedures. • • • . • • • • • • • • . 11 Sources of Data • . • • • • • . • . 12 Related Literature • . • • • . • • . 14 General Social and Dance History • . • . 14 Literature Concerning Massine .• • . • • • 18 Literature Concerning Decorative Artists for Massine Ballets • • • . • • • • • . 21 Literature Concerning Musicians/Composers for Massine Ballets • • • . -

January/February 2012

MGS Mission Statement Promote the guitar in all its stylistic and cultural diversity through sponsorship of public forums, concerts, and workshops. Serve as an educational and social link between the community and amateur and professional guitarists of all ages. A Publication of the Minnesota Guitar Society • P.O. Box 14986 • Minneapolis, MN 55414 JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2012 VOL. 28 NO. 1 We Bring the World of Music to You! The Beijing Guitar Duo Zoran Dukić from China at Sundin Hall at Sundin Hall on Sat., Jan. 21st on Sat., Feb. 18th e are delighted that the second half of our 2011 12 o classical guitar duo may be attracting more atten- concert series at Sundin Music Hall starts with the first tion these days than the Beijing Guitar Duo, composed appearance in Minnesota by one of the most celebrated of Meng Su and Yameng Wang, natives of China who Wclassical guitarists in the world, Zoran Dukić. In addition to his Ncurrently reside in the U.S. We are thrilled that they will be our performance on Saturday, January 21st, Dukić will be giving a February guest artists. Their concert is Saturday, Feb. 18th at 8 pm. masterclass (also at Sundin Hall) the next day. See sidebar for more They will conduct a masterclass on Friday the 17th at 2 pm. Both information. Members of our board, and others, who have had the will be at Sundin Music Hall. See sidebars for more info, and for opportunity to hear or meet the artist all rave about his tremendous details of their program. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

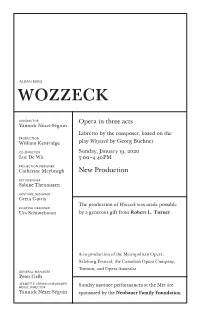

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

A Symphonic Psalm, After a Drama by René Morax King David

ELLIOT JONES MUSIC DIRECTOR A Symphonic Psalm, after a drama by René Morax Music by Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) Please silence all cellular phones and other electronic devices King David PART I 1. Introduction (Orchestra & Narrator) 2. The song of David, the shepherd: God shall be my shepherd kind. 3. Psalm: All praise to him, the Lord of glory, the everlasting God my helper. 4. Fanfare and entry of Goliath 5. Song of victory: David is great, the Philistines overthrown. Chosen of God is he. 6. Psalm: In the Lord I put my faith, I put my trust. 7. Psalm: O had I wings like a dove, then I would fly away and be at rest. 8. Song of the prophets: Man that is born of a woman lives but a little while. 9. Psalm: Pity me Lord, for I am weak. 10. Saul’s camp 11. Psalm: God, the Lord shall be my light and my salvation. What cause have I to fear? 12. Incantation of the Witch of Endor 13. March of the Philistines 14. The lament of Gilboa: Ah! Weep for Saul. 1 PART II ORCHESTRA 15. Song of the daughters of Israel: Sister, oh sing thy song! Never has God forsaken us. 16. The dance before the ark: Mighty God be with us, O splendor of the morn. FLUTE and PICCOLO CELLO Alexander Lipay, Paula Redinger Anne Gratz INTERMISSION OBOE and ENGLISH HORN BASS PART III Marquise Demaree Dylan DeRobertis 17. Song: Now my voice in song up-soaring shall loud proclaim my king afar. 18.