The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara Into a Plantation Parody, 52 Case W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Scarlet O' Hara's Ambitions in Margaret Mitchell's Gone

Chapter 3 The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions and Her Ways to Obtain Them I begin the analysis by revealing the factors of O’Hara’s two ambitions, namely the willingness to rebuild Tara and the desire to win Wilkes’ love. I divide this chapter into two main subchapters. The first subchapter is about the factors of the two ambitions that Scarlett O’Hara has, whereas the second subchapter explains how she tries to accomplish those ambitions. 3.1. The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions The main female character in Gone with the Wind has two great ambitions; her desires to preserve the family plantation called Tara, and to win Ashley Wilkes’ love by supporting his family’s needs. Scarlett O’Hara herself confesses that “Every part of her, almost everything she had ever done, striven after, attained, belonged to Ashley, were done because she loved him. Ashley and Tara, she belonged to them” (Mitchell, 1936, p.826). I am convinced that there are many factors which stimulate O’Hara to get these two ambitions. Thus, I use the literary tools: the theories of characterization, conflict and setting to analyze the factors. 3.1.1. The Ambition to Preserve Tara Scarlett O’Hara’s ambition to preserve the family’s plantation is stimulated by many factors within her life. I divide the factors that incite Scarlett O’Hara’s ambitions into two parts, the factors found before the war and after. The factors before the war are the sense of belonging to her land, the Southern tradition, and Tara which becomes the source of income. -

The Depiction of Women and Slavery in Margaret Mitchell's

“Tomorrow is Another Day”: The Depiction of Women and Slavery in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind and Robert Hicks’ The Widow of the South. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter I: Before the Civil War ........................................................................................ 5 Chapter II: During the Civil War .................................................................................... 12 Chapter III: After the Civil War ..................................................................................... 23 Conclusion..………………………………………………………………………….....31 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………34 1 Introduction Gone with the Wind and The Widow of the South are both Civil War novels written by first time writers. Margaret Mitchell‘s Gone with the Wind was published in 1936 and Robert Hicks‘ The Widow of the South was published in 2005. These two novels are written nearly seventy years apart. The protagonists of these two Civil War novels are very different, but still it is worth taking a look at the difference in attitude that the two novelists have in regard to women and slavery in the seventy-year span between the two novels. It is interesting to take a closer look at the portrayal by the two authors of the kind of lives these women lived, and what similarities and differences can be seen in the protagonists as pertaining to their education and upbringing. Also, how the women‘s lives were affected by living in a society which condoned slave ownership. The Civil War brought about changes in the women‘s lives both during its course and in its aftermath. Not only were the lives of the women affected but that of the slaves as well. The authors, through their writing, depicted aspects of the institution of slavery, especially how the slave hierarchy worked and what made one slave ―better‖ than the next. -

Interpretation of Scarlett's Land Complex in Gone with the Wind

102 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN ENGINEERING AND SOCIETY, VOL.1, NO.4, Interpretation of Scarlett‘s Land Complex in Gone with the Wind from the Perspective of Humanity Shutao Zhou College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University, Daqing 163319, China [email protected] Abstract: The famous novel Gone with the Wind by Tara was leisurely and wealthy. In this context, a Margaret Mitchell takes the Civil War as the young girl who was just sixteen years old lived a background. With the three marriage experiences of carefree life without a single worry, and the only Scarlett as the main line, her strong feeling of land thing she thought of was how to attract the attention complex runs through the whole book. The red land of men. She did not realize the importance of land at at Tara witnessed Scarlett‘s gradual growth and all. maturity, revealing the eternal blood ties between When her father persuaded Scarlett to give up her land and Scarlett. This paper, by analyzing Scarlett‘s obsession with Ashley and give Tara to her, she life course, explores the development of the land would not mind or even be hostile to the idea of complex which is a process from unconsciousness to being the master of the land. As her father gave her fight for the land. Scarlett‘s land complex gave her a the generous gift, she said in fury, ―I wouldn‘t have vivid image. Cade on a silver tray,‖ ―And I wish you‘d quit Key words: Scarlett; Tara; Land Complex pushing him at me! I don‘t want Tara or any old plantation. -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

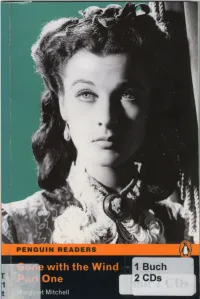

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Gone with the Wind – Part Two Book Key 23–24 Open Answers 25 Rhett Will Lend Melanie and Ashley the Money to Buy 1 Open Answers the Sawmills from Scarlett

PENGUIN READERS Answer keys LEVEL 4 Teacher Support Programme Gone with the Wind – Part Two Book key 23–24 Open answers 25 Rhett will lend Melanie and Ashley the money to buy 1 Open answers the sawmills from Scarlett. 2 a will. Open answers 26 Because Bonnie’s eyes are just like Gerald O’Hara’s, b He was a man of honour and she knew he would and the words she says are almost the same as his not break the oath he had taken. before his riding accident. 3 a Scarlett 27 Rhett won’t let them take her body from the house. b Jonas Wilkerson 28 When Melanie is dying. c Mammy 29 After Melanie dies and Scarlett realises she doesn’t love d Aunt Pitty Ashley after all. e Rhett 30 To go home to Tara and to get Rhett back. 4 She wants his money. 31–35 Open answers 5 Her hands are rough from work. 6–7 Open answers Discussion activities key 8 a fussy 1–3 Open answers b rape 4 guide students using information on page 2 of the c sawmill Teacher’s notes. d candle 5–12 Open answers 9 a funeral b owe Activity worksheets key 10 a He tells her he has money and business ideas. 1 a Scarlett O’Hara b Tara c Ashley Wilkes b She says she went to the Yankees to try to sell them d Melanie Hamilton e Charles Hamilton clothes for their wives. She tells him Suellen is f Rhett Butler g Wade h Atlanta going to marry Tony Fontaine because she got tired i Melanie Hamilton j Rhett Butler k Tara of waiting for Frank. -

Happy 75Th Anniversary

Literature County girlhood home, Tara. Clayton County was designated the official home of Gone with the Wind by Mitchell’s brother Stephens. All around were signs that this is truly GWTW country: Tara Elementary School, Tara Wedding Chapel, Tara Gone with the Wind Florist and – well, you get the idea. The county has even had a couple of Scarletts: Melly Meadows, a striking Vivien Leigh lookalike who traveled worldwide in this role, delighting Happy 75th Anniversary everyone she meets with her fiddle-dee-dees and, more recently, By Lillian Africano Cynthia Evans. My GWTW orientation began at the Road to Tara Museum, housed in the 1867 Jonesboro Railroad Station, Gone with the Wind about 15 miles south of Atlanta. Movie Set This relatively small museum has BELOW Gone with the Wind drawn Windies from all over the Movie Poster world; the guest book includes visitors from Norway, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia, largest collections of GWTW At the Patrick Cleburne Memorial the U.K., China and Japan. autographed photos. Olivia de Confederate Cemetery, where some Haviland, who played Melly and who 1,000 fallen soldiers from the Battle Here is so much to delight the most celebrated her 98th birthday in July, of Jonesboro are buried, Bonner, who dedicated fan: first editions of the is here of course, but so are the has taken part in past re-enactments novel, autographed photos, costumes movie’s bit players, such as the of the battle, vividly described the (including the pantalets worn by Tarleton twins. (Actor George ferocity of the two-day combat. -

Subject-Verb Agreement

SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT Finding the Subject and the Verb The subject in a sentence names the person or thing performing the action expressed in the predicate (= the verb, verbs, or verb phrases), which describes the action. An easy trick to find the verb(s) in a sentence is to change the tense in the sentence. The verb(s) will change if you do this, but nothing else will. Jean works at the grocery store. She stocks shelves, works the cash register, and helps the manager lock up at night. (present tense) Last year, Jean worked at the grocery store. She stocked shelves, worked the cash register, and helped the manager lock up at night. (past tense) To find the subject, you simply ask “who or what performs the action?” In the above example, who works at the store, stocks shelves, and helps the manager? Jean – so there is the subject. • In English, verbs take the same form for all persons with one exception: the third person singular in the present tense. For all subjects that can be replaced with he, she, or it, you need to add –s to the verb in the present tense. If the verb is “to be,” use the form is or was. Singular Plural I am poor. I work two jobs. We are poor. We work two jobs. You are poor. You work two jobs. You are poor. You work two jobs. He/she/it is poor. He/she works two jobs. They are poor. They work two jobs. • Different subjects joined by “and” (= compound subjects) are nearly always plural: Scarlett and Melanie nurse the injured soldiers. -

An Incredible Investment Opportunity the Twelve Oaks in a Truly

An Incredible Investment Opportunity The Twelve Oaks in a truly exceptional business opportunity. It is already income-producing, profitable, and award-winning. There are four different avenues for producing revenue with all permits already in place: as a Bed & Breakfast, an event venue, a historic site offering tours, and as a location for filming located right in the heart of the original “Hollywood of the South” in Covington, GA, which is an area for tremendous growth and part of the metro Atlanta area. The world’s busiest international airport is just 38 miles from the property and Covington houses its own regional airport as well. Georgia welcomes over 100 million tourists per year1 and approximately 50 million visit the Atlanta area. Income Opportunities: 1. Bed & Breakfast/Luxury Inn: The property opened as a Bed & Breakfast for the first time in late 2012. Every year since opening has brought tremendous growth and unheard of awards for a “new” inn. Some of the awards won and recognitions received follow: • Southern Living South’s Best Inns: Just last year (2018), the readers of Southern Living voted the Twelve Oaks as one of the South’s Best Inns in the #4 spot! This is amazing as a relatively “new” inn opened just six years prior beat out places like The Cloister, Blackberry Farm, Grove Park Inn, etc. • Tripadvisor Hall of Fame (2019 and 2018). Every year Tripadvisor gives a Certificate of Excellence to places with amazing reviews. The Twelve Oaks has received a Certificate of Excellence for every single year in business and was thus inducted into the “Hall of Fame” in 2018 and just received the designation for 2019 as well. -

The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara Into a Plantation Parody

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 16 2002 The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara into a Plantation Parody Jeffrey D. Grossett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey D. Grossett, The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara into a Plantation Parody, 52 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1113 (2002) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol52/iss4/16 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE WIND DONE GONE: TRANSFORMING TARA INTO A PLANTATION PARODY In June 2001, amid a flurry of legal wrangling, Houghton Mifflin Company sent to print Alice Randall's first novel, The Wind Done Gone.' Described by the publisher as a "provocative literary parody that explodes the mythology perpetrated by a Southern Classic,"'2 the novel takes direct aim at Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind,3 the definitive epic novel of the Civil War era South.4 Targeting the racist and paternalistic treatment of African-American slaves perva- sive throughout Gone with the Wind,5 Randall's novel begins by re- telling the Gone with the Wind story from the perspective of an ille- gitimate mulatto slave, Cynara.6 It then proceeds to the tales that Gone with the Wind left untold-the events of Scarlett's anxiously awaited "tomorrow," and the sad conclusion to Scarlett7 and Rhett's tempestuous relationship, as seen through Cynara's eyes. -

Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson Dissertation Submitt

The Wind Goes On: Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Emily M. Satterwhite, Co-Chair David P. Cline, Co-Chair Marian B. Mollin Scott G. Nelson February 13, 2018 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Gone with the Wind, Mass Media and History, US South, Slavery, Civil War, Reconstruction, African American History, Memory, Race Relations, Whiteness, Nationalism, Tourism, Audiences Copyright: Taulby H. Edmondson 2018 The Wind Goes On: Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson ABSTRACT Published in 1936, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind achieved massive literary success before being adapted into a motion picture of the same name in 1939. The novel and film have amassed numerous accolades, inspired frequent reissues, and sustained mass popularity. This dissertation analyzes evidence of audience reception in order to assess the effects of Gone with the Wind’s version of Lost Cause collective memory on the construction of the Old South, Civil War, and Lost Cause in the American imagination from 1936 to 2016. By utilizing the concept of prosthetic memory in conjunction with older, still-existing forms of collective cultural memory, Gone with the Wind is framed as a newly theorized mass cultural phenomenon that perpetuates Lost Cause historical narratives by reaching those who not only identify closely with it, but also by informing what nonidentifying consumers seeking historical authenticity think about the Old South and Civil War. -

Gone with the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy

Gone With the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy (Tara is the beautiful homeland of Scarlett, who is now talking with the twins, Brent and Stew, at the door step.) BRENT What do we care if we were expelled from college, Scarlett. The war is going to start any day now so we would have left college anyhow. STEW Oh, isn't it exciting, Scarlett? You know those poor Yankees actually want a war? BRENT We'll show 'em. SCARLETT Fiddle-dee-dee. War, war, war. This war talk is spoiling all the fun at every party this spring. I get so bored I could scream. Besides, there isn't going to be any war. BRENT Not going to be any war? STEW Ah, buddy, of course there's going to be a war. SCARLETT If either of you boys says "war" just once again, I'll go in the house and slam the door. BRENT But Scarlett honey.. STEW Don't you want us to have a war? BRENT Wait a minute, Scarlett... STEW We'll talk about this... BRENT No please, we'll do anything you say... SCARLETT Well- but remember I warned you. BRENT I've got an idea. We'll talk about the barbecue the Wilkes are giving over at Twelve Oaks tomorrow. STEW That's a good idea. You're eating barbecue with us, aren't you, Scarlett? SCARLETT Well, I hadn't thought about that yet, I'll...I'll think about that tomorrow. STEW And we want all your waltzes, there's first Brent, then me, then Brent, then me again, then Saul. -

Gone with the Wind and the Lost Cause Caitlin Hall

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2019 Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause Caitlin Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Caitlin, "Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause" (2019). University Honors Program Theses. 407. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/407 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gone with the Wind and the Myth of the Lost Cause An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature. By Caitlin M. Hall Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind is usually considered a sympathetic portrayal of the suffering and deprivation endured by Southerners during the Civil War. I argue the opposite, that Mitchell is subverting the Southern Myth of the Lost Cause, exposing it as hollow and ultimately self-defeating. Thesis Mentor:________________________ Dr. Joe Pellegrino Honors Director:_______________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2019 Department Name University Honors Program Georgia Southern University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements