Fragmented Identity of the Chakmas in Mizoram: Citizens Or Illegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

IPP: Bangladesh: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project

Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project (RRP BAN 42248) Indigenous Peoples Plan March 2011 BAN: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Prepared by ANZDEC Ltd for the Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs and Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2011) Currency unit – taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0140 $1.00 = Tk71.56 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADR – alternative dispute resolution AP – affected person CHT – Chittagong Hill Tracts CHTDF – Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Facility CHTRC – Chittagong Hill Tracts Regional Council CHTRDP – Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project CI – community infrastructure DC – deputy commissioner DPMO – district project management office GOB – Government of Bangladesh GPS – global positioning system GRC – grievance redress committee HDC – hill district council INGO – implementing NGO IP – indigenous people IPP – indigenous peoples plan LARF – land acquisition and resettlement framework LCS – labor contracting society LGED – Local Government Engineering Department MAD – micro agribusiness development MIS – management information system MOCHTA – Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 1 CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. -

World Bank Document

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 Mizoram State Road Project II (MSTP II) The Government of India has requested World Bank for financing rehabilitation, widening Public Disclosure Authorized and strengthening of State Highways and District Roads in the State of Mizoram, and enhances connectivity. In line with this request, Mizoram State Roads Project II (MSRP II) is proposed. The proposed roads under MSRP II are shown in Map-1. The MSRP II is to be implemented in two groups. The proposed group –I and group –II project corridors are shown in figure 1 and table 1. Group –I of the project is under project preparation. Project Preparatory Consultants1 (PPC) is assisting MPWD in project preparation. The MSR II has been categorised as category ‘A’ project. Table 1.1 – Proposed Project Roads under MSRP II Group -1 District(s) Length i. Champhai – Zokhawthar Champhai 27.5 km, (E-W road to Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized border) ii Chhumkhum-Chawngte Lunglei 41.53 km, (part of original N-S road alignment) Group – 2 i. Lunglei - Tlabung - Lunglei 87.9 km, (E-W road to Bangladesh Kawrpuichhuah border) ii. Junction NH44A (Origination) – Mamit&Lunglei 83 km Chungtlang – Darlung – Buarpui iii. Buarpui – Thenlum – Zawlpui Lunglei 95 km iv Chawngte including bridge to Lawngtlai 76 km Public Disclosure Authorized BungtlangSouth up to Multimodal Road junction v. Zawlpui – Phairuangkai Lunglei 30 km 1.1 Champhai – Zokhawthar road The Mizoram Public Works Department has decided to upgrade the existing 28.5 km Champhai – Zokhawthar road from single road state highway standard to 2-Lane National Highway Standard. This road passes through a number of villages like Zotlang, Mualkwai, Melbuk Zokhawthar and part of Champhai town etc. -

Edited by – Ashis Roy

Dam Edited by – Ashis Roy Dam a structure built across a stream, river, or estuary to store water. A reservoir is created upstream of the dam to supply water for human consumption, irrigation, or industrial use. Reservoirs are also used to reduce peak discharge of floodwater, to increase the volume of water stored for generating hydroelectric power, or to increase the depth of water in a river so as to improve navigation and provide for recreation. Dams are usually of two basic types - masonry (concrete) and embankment (earth or rock-fill). Masonry dams are used to block streams running through narrow gorges, as in mountainous terrain; though such dams may be very high, the total amount of material required is much less. The choice between masonry and earthen dam and the actual design depend on the geology and configuration of the site, the functions of the dam, and cost factors. Auxiliary works for a dam include spillways, gates, or valves to control the discharge of surplus water downstream from the reservoir; an intake structure conducting water to a power station or to canals, tunnels, or pipelines for more distant use; provision for evacuating silt carried into the reservoir; and means for permitting boats or fish to cross the dam. A dam therefore is the central structure in a multipurpose scheme aiming at the conservation of water resources. Water levels in the reservoir upstream is controlled by opening and closing gates of the spillway which acts as the safety valve of the dam. In addition to spillways, openings through dams are also required for drawing off water for irrigation and water supply, for ensuring a minimum flow in the river for riparian interests downstream, for generating power, and for evacuating water and silt from the reservoir. -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

A Study of the Chakma Refugees in Mizoram Suparna Nandy Kar Ph.D

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES ISSN 2321 - 9203 www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES Migration and Displacement Refugee Crisis: A Study of the Chakma Refugees in Mizoram Suparna Nandy Kar Ph.D. Scholar, Diphu Campus, Assam University, Assam Dr. K.C. Das Associate Professor, Diphu Campus, Assam University, Assam Abstract: The Chakmas constitute one of the ethnic groups of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (C H T’s), where 98 percent of the inhabitants of the hill region are the indigenous people of Mongoloid stock until the Muslim infiltrators swamped over the area. The Chakma ethnic groups are the most dominant and important tribe. They are Buddhist by faith. According to Encyclopaedia of South Asian Tribes Chakmas have descended from King Avirath of the Sakya dynasty. They belong to a tribal clan of the Tibe to - Burman race and came to the area when Burmans destroyed the Arakan Kingdom. Arakanese dissidents who were against the Burmese administration took shelter as refugees in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. After the partition of the country the C H T was annexed to Pakistan .Some of them stood against the policy of the Government of Pakistan because they were suppressed and many of them had to cross the border and enter into India and Burma for the protection of their lives and family. Later on , Pakistan Government took the policy of setting up of a Hydro Electric Project over the river Karnaphuli in the C H T. The high water level of Kaptai Hydro Electric Project inundated a vast Chakma inhabited area. -

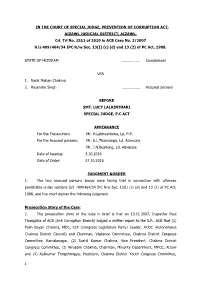

1 in the COURT of SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION of CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in AC

IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION OF CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in ACB Case No. 2/2007 U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988. STATE OF MIZORAM ……………… Complainant VRS 1. Rasik Mohan Chakma 2. Rosendro Singh ……………… Accused persons BEFORE SMT. LUCY LALRINTHARI SPECIAL JUDGE, P.C ACT APPEARANCE For the Prosecution: Mr. H.Lalmuankima, Ld. P.P. For the Accused persons: Mr. S.L.Thansanga, Ld. Advocate Mr. J.N.Bualteng, Ld. Advocate Date of hearing: 3.10.2016 Date of Order: 27.10.2016 JUDGMENT &ORDER 1. The two accused persons above were facing trial in connection with offences punishable under sections U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988, and the court deliver the following judgment. Prosecution Story of the Case: 2. The prosecution story of the case in brief is that on 13.11.2007, Inspector Paul Thangzika of ACB (Anti Corruption Branch) lodged a written report to the S.P., ACB that (1) Pulin Bayan Chakma, MDC, CLP (Congress Legislature Party) Leader, ACDC (Autonomous Chakma District Council) and Chairman, Vigilance Committee, Chakma District Congress Committee, Kamalanagar, (2) Sushil Kumar Chakma, Vice President, Chakma District Congress Committee, (3) Nirupam Chakma, Chairman, Minority Department, MPCC, Aizawl and (4) Kalikumar Tongchongya, President, Chakma District Youth Congress Committee, 1 Kamalanagar had submitted a written complaint to His Excellency, the Governor of Mizoram against the authority of Chama Autonomous District Council for dishonestly mis-utilizing the Centrally sponsored Scheme (CSS) under the scheme of Rashtriya Sam Vikash Yojana (RSVY). -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

Of Bangladesh: an Overview

Chapter 3 Socioeconomic Status and Development of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh: An Overview MIZANUR RAHMAN SHELLEY Chairman Centre for Development Research Bangladesh (CDRB) 3.1 Introduction The processes of growth, poverty alleviation, and sustainable resource management in the Chittagong Hill Tracts’ (CHT) area of Bangladesh were seriously obstructed by 20 years of insurgency and armed conflict in the region which lasted until recent times. This period of insurgency in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh was brought to a formal end on the 2nd December 1997 with the signing of a peace agreement between the Bangladesh National Committee on the Chittagong Hill Tracts, representing the Government of Bangladesh, and the ‘Parbatya Chattagram Janasanghati Samity’ (PCJSS), representing the political wing of the insurgent ‘Shanti Bahini’, (Peaceful Sister(s) composed mainly of the militants among the tribe of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). The two sides affirmed their full and firm allegiance to territorial integrity, sovereignty, and the constitution of Bangladesh. The agreement was the outcome of a political process of peaceful dialogues and negotiations that extended over the tenures of three successive governments, dating from the eighties. Drawn up, finalised, and signed within a year and a half of the inception of the tenure of the Awami League Government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the peace agreement accommodated the demands for cultural, religious, and economic autonomy and equity of the hill people within the framework of sovereign 107 Untitled-4 107 7/19/2007, 1:07 PM Bangladesh and hence successfully put an end to the armed violence in the strategic and economically promising territory.