A Baseline Survey of Minority Concentration Districts of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 Mizoram State Road Project II (MSTP II) The Government of India has requested World Bank for financing rehabilitation, widening Public Disclosure Authorized and strengthening of State Highways and District Roads in the State of Mizoram, and enhances connectivity. In line with this request, Mizoram State Roads Project II (MSRP II) is proposed. The proposed roads under MSRP II are shown in Map-1. The MSRP II is to be implemented in two groups. The proposed group –I and group –II project corridors are shown in figure 1 and table 1. Group –I of the project is under project preparation. Project Preparatory Consultants1 (PPC) is assisting MPWD in project preparation. The MSR II has been categorised as category ‘A’ project. Table 1.1 – Proposed Project Roads under MSRP II Group -1 District(s) Length i. Champhai – Zokhawthar Champhai 27.5 km, (E-W road to Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized border) ii Chhumkhum-Chawngte Lunglei 41.53 km, (part of original N-S road alignment) Group – 2 i. Lunglei - Tlabung - Lunglei 87.9 km, (E-W road to Bangladesh Kawrpuichhuah border) ii. Junction NH44A (Origination) – Mamit&Lunglei 83 km Chungtlang – Darlung – Buarpui iii. Buarpui – Thenlum – Zawlpui Lunglei 95 km iv Chawngte including bridge to Lawngtlai 76 km Public Disclosure Authorized BungtlangSouth up to Multimodal Road junction v. Zawlpui – Phairuangkai Lunglei 30 km 1.1 Champhai – Zokhawthar road The Mizoram Public Works Department has decided to upgrade the existing 28.5 km Champhai – Zokhawthar road from single road state highway standard to 2-Lane National Highway Standard. This road passes through a number of villages like Zotlang, Mualkwai, Melbuk Zokhawthar and part of Champhai town etc. -

1 in the COURT of SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION of CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in AC

IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL JUDGE, PREVENTION OF CORRUPTION ACT, AIZAWL JUDICIAL DISTRICT, AIZAWL. Crl. Trl No. 1511 of 2010 in ACB Case No. 2/2007 U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988. STATE OF MIZORAM ……………… Complainant VRS 1. Rasik Mohan Chakma 2. Rosendro Singh ……………… Accused persons BEFORE SMT. LUCY LALRINTHARI SPECIAL JUDGE, P.C ACT APPEARANCE For the Prosecution: Mr. H.Lalmuankima, Ld. P.P. For the Accused persons: Mr. S.L.Thansanga, Ld. Advocate Mr. J.N.Bualteng, Ld. Advocate Date of hearing: 3.10.2016 Date of Order: 27.10.2016 JUDGMENT &ORDER 1. The two accused persons above were facing trial in connection with offences punishable under sections U/s 409/464/34 IPC R/w Sec. 13(I) (c) (d) and 13 (2) of PC Act, 1988, and the court deliver the following judgment. Prosecution Story of the Case: 2. The prosecution story of the case in brief is that on 13.11.2007, Inspector Paul Thangzika of ACB (Anti Corruption Branch) lodged a written report to the S.P., ACB that (1) Pulin Bayan Chakma, MDC, CLP (Congress Legislature Party) Leader, ACDC (Autonomous Chakma District Council) and Chairman, Vigilance Committee, Chakma District Congress Committee, Kamalanagar, (2) Sushil Kumar Chakma, Vice President, Chakma District Congress Committee, (3) Nirupam Chakma, Chairman, Minority Department, MPCC, Aizawl and (4) Kalikumar Tongchongya, President, Chakma District Youth Congress Committee, 1 Kamalanagar had submitted a written complaint to His Excellency, the Governor of Mizoram against the authority of Chama Autonomous District Council for dishonestly mis-utilizing the Centrally sponsored Scheme (CSS) under the scheme of Rashtriya Sam Vikash Yojana (RSVY). -

List of Organisations/Individuals Who Sent Representations to the Commission

1. A.J.K.K.S. Polytechnic, Thoomanaick-empalayam, Erode LIST OF ORGANISATIONS/INDIVIDUALS WHO SENT REPRESENTATIONS TO THE COMMISSION A. ORGANISATIONS (Alphabetical Order) L 2. Aazadi Bachao Andolan, Rajkot 3. Abhiyan – Rural Development Society, Samastipur, Bihar 4. Adarsh Chetna Samiti, Patna 5. Adhivakta Parishad, Prayag, Uttar Pradesh 6. Adhivakta Sangh, Aligarh, U.P. 7. Adhunik Manav Jan Chetna Path Darshak, New Delhi 8. Adibasi Mahasabha, Midnapore 9. Adi-Dravidar Peravai, Tamil Nadu 10. Adirampattinam Rural Development Association, Thanjavur 11. Adivasi Gowari Samaj Sangatak Committee Maharashtra, Nagpur 12. Ajay Memorial Charitable Trust, Bhopal 13. Akanksha Jankalyan Parishad, Navi Mumbai 14. Akhand Bharat Sabha (Hind), Lucknow 15. Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, New Delhi 16. Akhil Bharatiya Adivasi Vikas Parishad, New Delhi 17. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 18. Akhil Bharatiya Baba Saheb Dr. Ambedkar Samaj Sudhar Samiti, Mirzapur 19. Akhil Bharatiya Bhil Samaj, Ratlam District, Madhya Pradesh 20. Akhil Bharatiya Bhrastachar Unmulan Avam Samaj Sewak Sangh, Unna, Himachal Pradesh 21. Akhil Bharatiya Dhan Utpadak Kisan Mazdoor Nagrik Bachao Samiti, Godia, Maharashtra 22. Akhil Bharatiya Gwal Sewa Sansthan, Allahabad. 23. Akhil Bharatiya Kayasth Mahasabha, Amroh, U.P. 24. Akhil Bharatiya Ladhi Lohana Sindhi Panchayat, Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh 25. Akhil Bharatiya Meena Sangh, Jaipur 26. Akhil Bharatiya Pracharya Mahasabha, Baghpat,U.P. 27. Akhil Bharatiya Prajapati (Kumbhkar) Sangh, New Delhi 28. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtrawadi Hindu Manch, Patna 29. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Brahmin Mahasangh, Unnao 30. Akhil Bharatiya Rashtriya Congress Alap Sankyak Prakosht, Lakheri, Rajasthan 31. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan 32. Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Congress, Mumbai 33. -

Literates by Residence - Persons

Census of India 2011 Provisional Population Totals Literates by residence - Persons State/ State/District Literates District (Persons) Code 2011 Total Rural Urban 1 2 73 74 75 15 Mizoram 847,592 368,672 478,920 01 Mamit 60,979 49,349 11,630 02 Kolasib 66,510 27,613 38,897 03 Aizawl 346,465 75,250 271,215 04 Champhai 96,601 57,537 39,064 05 Serchhip 55,102 27,417 27,685 06 Lunglei 116,669 63,041 53,628 07 Lawngtlai 63,524 46,579 16,945 08 Saiha 41,742 21,886 19,856 Literates by residence - Persons 400,000 Total Rural Urban 350,000 300,000 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 Mamit Kolasib Aizawl Champhai Serchhip Lunglei Lawngtlai Saiha Census of India 2011 Provisional Population Totals Literates by residence -Males State/ State/District Literates District (Males) Code 2011 Total Rural Urban 1 2 76 77 78 15 Mizoram 438,949 198,486 240,463 01 Mamit 33,427 27,371 6,056 02 Kolasib 34,438 14,514 19,924 03 Aizawl 172,974 38,947 134,027 04 Champhai 49,417 29,718 19,699 05 Serchhip 27,893 13,881 14,012 06 Lunglei 62,365 34,582 27,783 07 Lawngtlai 36,810 27,986 8,824 08 Saiha 21,625 11,487 10,138 Literates by residence - Males 200,000 180,000 160,000 140,000 Total Rural Urban 120,000 100,000 80,000 60,000 40,000 20,000 0 Mamit Kolasib Aizawl Champhai Serchhip Lunglei Lawngtlai Saiha Census of India 2011 Provisional Population Totals Literates by residence -Females State/ State/District Literates District (Females) Code 2011 Total Rural Urban 1 2 79 80 81 15 Mizoram 408,643 170,186 238,457 01 Mamit 27,552 21,978 5,574 02 Kolasib 32,072 13,099 -

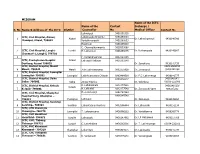

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Guidance for TB Notification in India

2012 Guidance for TB Notification in India Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Govt of India July 2012 For any queries, please write to [email protected] Guidance for TB Notification in India 2012 Sr No Contents: Page no 1 Background 2 2 Why should private health facilities notify TB? 3 3 Objectives 3 4 Minimum information requirement for TB notification 3 5 Definitions for TB notification 3 6 List of RNTCP endorsed TB diagnostics 4 7 Registration of the Health establishments for TB 5 notification 8 Mechanisms for TB notification 6 9 Responsibility of the district level nodal officer 7 10 Responsibility of the Local public health authority 7 11 Responsibility of the health worker 8 Annexures I Health Establishment registration form for TB Notification 9 II Undertaking for Health establishments not routinely 10 diagnosing / treating Tuberculosis patients III Formats for TB notification 11 IV List & contact details of Local Health Authority (Nodal 13 Officer) for TB notification 1 Guidance for TB Notification in India 2012 1 Background: Tuberculosis is a major public health problem in India. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of TB is the corner- stone of TB prevention and control strategy. India’s National TB Control programme provides quality assured diagnostic and treatment services to all the TB patients including necessary supportive mechanisms for ensuring treatment adherence and completion. The country has a huge private sector and it is growing at enormous pace. Private sector predominates in health care and TB treatment. Extremely large quantities of anti-TB drugs are sold in the private sector. -

The Mizoram Gazette Wuf,Cisftea

" • �'lJ1I"it The Mizoram Gazette EXTRAORDINARY Wuf,Cisftea [,y Authority Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) VOL - XXXII Aizawl, Saturday 6.12.2003 Agrahayana 15, S.B. 1925, Issue No. 370 ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi -110 001. Dated: the 6th December, 2003 t • 15 Agrahayana,1925 (Saka) NOTIFICATION No. 30S/MIZ-LN2003 :- Whereas, in pursuance of Notification No.H. 11018/2/2003-CEO, issued by the Governor of Mizoram on 27th October, 2003 under sub-section (2) of Section 15 of the Representationof the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951), a General Election has been held for the purpose of constitutinga new Legislative Assembly for theState ofMizoram; and Whereas, the results of theelections inall Assembly Constituencies in the said General Election have been declaredby the Returning Officers concernedexcept in20- Suangpuilawn(S T) Assembly Contituency, where counting of votes has not been completed. Now, therefore, in pursuance of section 73 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951), the Election Commission ofIndia hereby notifies the names of the Members elected for those constituencies,along withtheir party affiliation, if any, inthe SCHEDULEto this Notification. By order, K. AJAYA KUMAR SECRETARY ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Ex--370/2003 - 2 - SCHEDULE TO NOTIFICATION NO. 3081MIZ-LAl2003 DATED �. 6TH DECEMBER,2003 OF ELECTION COMMisSION OF INDIA • Name of the State: Mizoram S1. No. and Name of Name of theElected PartyAffiliation (if any) Assembly Constituency Member l. Tuipang(ST) P.P.Thawla Maraland Democratic Front Indian 2. Saiha(ST) S. Hiato National Congress 3. Sangau(ST) H.Rammawi MIZO National Front 4. -

Notable Bird Records from Mizoram in North-East India (Forktail 22: 152-155)

152 SHORT NOTES Forktail 22 (2006) Notable bird records from Mizoram in north-east India ANWARUDDIN CHOUDHURY The state of Mizoram (21°58′–24°30′N 92°16′–93°25′E) northern Mizoram, in March 1986 (five days), February is located in the southern part of north-east India (Fig. 1). 1987 (seven days) and April 1988 (5 days) while based in Formerly referred to as the Lushai Hills of southern Assam, southern Assam. During 2–17 April 2000, I visited parts it covers an area of 21,081 km2. Mizoram falls in the Indo- of Aizawl, Kolasib, Lawngtlai, Lunglei, Mamit, Saiha, Burma global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and Serchhip districts and surveyed Dampa Sanctuary and the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area and Tiger Reserve, Ngengpui Willdlife Sanctuary, (Stattersfield et al. 1998). The entire state is hilly and Phawngpui National Park and the fringe of Khawnglung mountainous. The highest ranges are towards east with Wildlife Sanctuary. This included 61 km of foot transect the peaks of Phawngpui (2,157 m; the highest point in along paths and streams, 2.5 km of boat transects along Mizoram) and Lengteng (2,141 m). The lowest elevation, the Ngengpui River and Palak Dil, and 1,847 km of road <100 m, is in the riverbeds near the borders with Assam transects. During 15–22 February 2001, I visited parts of and Bangladesh border. The climate is tropical monsoon- type with a hot wet summer and a cool dry winter. Table 1. Details of sites mentioned in the text. Temperatures range from 7° to 34°C; annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000 mm. -

The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority

Regd. No. NE 907 • The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority VOL. xxv Aizawl Friday, 1. 11. 1996 Kartika 10, S.E. 1918 Issue No. 44 Government of Mizoram Part I Appointments, Postings, Transfers, Powers, Leave and Other Personal Notioes and Order&. • (ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR) I • ! • NOTIFICATIO NS • No. A. 19015j1� 196-VIG the 1st November, 1996. On the expiry of his re-employ ment as Deputy Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch for period of 4 (four) months with effect from 1.7.1996 to 31.10 1996, Pu R. Doliana, Deputy Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch is released from the office of Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch on 31.10.96(AjN). T. Sangkunga, Deputy Secretary to the Govt. of Mizoram, Vigilance Department. No. A. 33012jlj96-HFW(L) the 28th October, 1996. The Governor of Mizoram is pleased to retire and release Pi Thanpari Pautu, Dy. Director (Nursing), Mizoram Aizawl who bas attained the age of superannuation retirement with effect from 31. 10. 1996 (A N)' She wiIl hand over charge to Director, Health & Family Welfare Department. Haukhum Hauzel, Commisioner to the Govt. of Mizoram, Health & Family Welfare Department. \ 2 No. A.l1 013/1/94-EDN(L): the 31st October, 1996. In the interest of Public Service, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to order tr:J.n<;f�r and posting of the fo llowing Lecturers to the Colleges shown against their nam�s with immediate effect. 51. Name of Lectura Present place New place Remarks No. of posting of posting I 2 3 4 5 • Pu T. -

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

Resutls for Gramin Dak Sevak for North Eastern Circle

Resutls for Gramin Dak Sevak for North Eastern Circle S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Manipur Imphal H.O Chakpikarong Gobok B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R1DC82FB64C36 SOWNDERYA M S.O (92.8) 2 Manipur Imphal H.O Chakpikarong Sajik Tampak GDS MD UR 1 R018457C4E49D THIYAM INAO S.O B.O SINGH (91.2) 3 Manipur Imphal H.O Chandel S.O Mittong B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R4C18B72F4591 KHUTLEIBAM MD KANOON HAQUE (91.8) 4 Manipur Imphal H.O Churachandp South Kotlein GDS BPM UR 1 R84F8FBA8DA21 PUKHRAMBAM ur S.O B.O VASKAR SINGH (91.2) 5 Manipur Imphal H.O Lamlong S.O Huidrom B.O GDS MD OBC 1 R24756BB59EAD SANGEETH M P (92.8889) 6 Manipur Imphal H.O Lamlong S.O Nongoda B.O GDS BPM SC 1 R1AC74CAF5489 CHINGTHAM LOYALAKPA SINGH (95) 7 Manipur Imphal H.O Litan S.O Semol B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R8723E884ED43 RUHANI ALI (91.2) 8 Manipur Imphal H.O Litan S.O Thawai B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R3A6764E447F4 SHYJIMOL C (94.6) 9 Manipur Imphal H.O Mao S.O Mao S.O GDS MD UR 1 R74DBE3D94C4B MD SARIF (91.2) 10 Manipur Imphal H.O Moreh S.O Bongjoi B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R5DB3F6B4AAF3 MD YAKIR HUSSAIN (91.2) 11 Manipur Imphal H.O Nambol S.O Bungte Chiru GDS BPM UR 1 R52EAF9243942 THOUDAM B.O MICHEAL SINGH (95) 12 Manipur Imphal H.O Nambol S.O Manamayang GDS BPM UR 1 R7AFF761A47A4 KUMAR MANGLAM B.O (93.1) 13 Manipur Imphal H.O Singhat S.O Behiang B.O GDS BPM UR 1 R53B454F6511B RITEZH THOUDAM (95) 14 Manipur Imphal H.O Yairipok S.O Angtha B.O GDS BPM OBC 1 R03184F4ECDC8 KOHILA DEVI G (95) 15 Manipur Imphal H.O Yairipok -

Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Department of Health and Family Welfare

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.178 TO BE ANSWERED ON THE 21ST DEEMBER, 2018 RANKING OF DISTRICT HOSPITALS *178. DR. KIRIT SOMAIYA: Will the Minister of HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE be pleased to state: (a) the total number of district hospitals in the country, State and districtwise; (b) whether the Ministry along with NITI Aayog has started ranking the district hospitals and if so, the details thereof; (c) the details of criteria, parameters, indicators, etc. followed in ranking district hospitals; (d) the timeframe to complete the ranking process of these hospitals; and (e) the manner in which the general public and patients will be benefited by this ranking? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE (SHRI JAGAT PRAKASH NADDA) (a) to (e) : A Statement is laid on the Table of the House. STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO.178* FOR 21ST DECEMBER, 2018 (a): Total number of district hospitals in the country, State and district wise is given at Annexure. (b): Ministry of Health and Family Welfare along with the NITI Aayog, has not started the ranking of District Hospitals. (c): A conceptual framework has been developed by NITI Aayog in consultation with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare to track performance of District Hospitals. The link of the framework indicating the criteria, parameters, indicators etc. is available on the link at http://niti.gov.in /content/tracking-performance- district-hospitals-health-our-hospitals. (d): The process for ranking of the District Hospitals is to be done on an annual basis.