Communalism in the British Punjab During 1937 to 1939: Focus on Religion and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christianity Page 3

CLINICAL CARE GUIDELINES RELIGIOUS DENOMINATION CARE GUIDELINES Author and position David Knight, Chaplain. Approved by St Richards Hospice, Worcester, Clinical Guidelines Committee Approval date Jan 2009 Review Date Jan 2011 Page 1 of 15 INDEX Christianity Page 3 Islam Page 5 Sikhism Page 7 Hinduism Page 9 Judaism Page 11 Buddhism Page 13 Author and position David Knight, Chaplain. Approved by St Richards Hospice, Worcester, Clinical Guidelines Committee Approval date Jan 2009 Review Date Jan 2011 Page 2 of 15 Christianity: Generally, it is hard to separate out Christianity from mainstream English culture. This should not be taken to mean that an individual Christian’s spiritual needs are predictable. Numbers: 2001 Census, UK adherents 42,000,000 persons (roughly three quarters of the population). General Information: • Christianity was founded around 2000 years ago by Jesus of Nazareth in the area of modern day Israel and Palestine. • ‘Christ’ is a Greek word meaning ‘Messiah’. Messiah is a Hebrew word meaning ‘Anointed One’. • Christianity, along with Islam, has adopted the Jewish Scriptures as part of its collection of sacred writings. • Christianity is the world’s largest, most adaptable religion. • There is a wide variety within world Christianity of beliefs, ethical standpoints and forms of worship. • Jesus never wrote a book, never went to university and never travelled more than a few weeks walk away from his birthplace. He was a skilled craftsman who worked in (probably) the family carpentry business in Nazareth until the age of 30. • This apparently modest background does not prepare us for what happened next. • For three years he travelled on foot around the villages and towns of Galilee and environs, teaching, healing and gathering a sizeable following. -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

SITUATIONS VACANT Punjab Vocational Training Council (PVTC) Is the Largest Vocational Training Provider of Pakistan

SITUATIONS VACANT Punjab Vocational Training Council (PVTC) is the largest vocational training provider of Pakistan. It is an autonomous corporate body of Punjab Government having 348 VTIs with annual capacity of 200,000 trainees. Our mission is to alleviate poverty by imparting demand driven skills training to youth at their door step by involving private sector to enhance employability. To strength its operations, PVTC is hiring following staff in its offices and Vocational Training Institutes (VTIs):- No. Name of Post of Required Qualification & Post-Qualification Experience Initial Place of Posting Post BCS (4Years) BSCS (4Years)/BS-IT (4 Years) / BSc-Computer Assistant Engineering (4 Years)/ BSC. Software Engineering (4 Years) or Manager MIS 01 MCS / MIT /MSc-IT (2Years) held after 4 years Computer related PVTC Head Office, Lahore (Financials) bachelor degree from recognized university having 2 years of post-qualification experience in the relevant field. BCS (4Years) BSCS (4Years)/BS-IT (4 Years) / BSc-Computer Assistant Engineering (4 Years)/ BSC. Software Engineering (4 Years) or Manager MIS 01 MCS / MIT /MSc-IT (2Years) held after 4 years Computer related PVTC Head Office, Lahore (Web bachelor degree from recognized university having 2 years of Development) post-qualification experience in the relevant field. M.Com/MBA (Accounting & Finance) / Master in Finance / M.Sc. Assistant (Financial Management)/ MS (Accounting)/BBA (4 Years, Manager (Finance 01 Accounting & Finance) / ACMA from a recognized institute with Area Office Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur & Audit) at least 02 years of post-qualification experience in the relevant field. B.Com/ BBA (Accounting & Finance) from recognized university Supervisor 01 having 3 years of post-qualification experience in the relevant PVTC Head Office, Lahore (Provident Fund) field. -

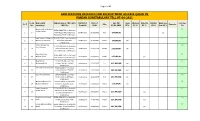

Applications Received for Recruitment As Naib Qasid in Punjab Constabulary Till 07-04-2021

Page 1 of 85 APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR RECRUITMENT AS NAIB QASID IN PUNJAB CONSTABULARY TILL 07-04-2021 Form Name with Address as per CNIC with District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. # Edu: Remarks No. parentage CNIC No. Domicile Birth 07-04-2021 57% 15 % 05 % 03 % Son 20 % Fit Muhammad Tallat Bhatti Fit 35404-5665873-5 r/o Muhallah s/o Amanullah 1 3 Makki Nagar Mureedkey road Sheikhupura 01/08/2002 FSC 18Y,8M,6D yes Farooqabad Distt: sheikhupura Syed Usman Ali Shah s/o 35404-8415306-5 r/o Chak Wahi Fit 2 4 Mazhar Hussain Shah No.522 PO same Distt: Sheikhupura 01/04/2003 Matric 18Y,0M,6D yes sheikhupura Nabeel Shakoor s/o Fit 35404-8509339-3 r/o Muhallah Abdul Shakoor 3 10 Christian Basti near Church Sheikhupura 07/02/1998 Middle 23Y,2M,0D yes Farooqabad Distt: Sheikhupura Akash Masih s/o Fit 35404-0663146-5 r/o Esa Nagri 4 20 Mukhtar Masih sheikhupura 05/12/1999 Middle 21Y,4M,2D yes road Chhapa road Sheikhupura Majid Ali s/o 35404-3285488-7 r/o Tibbi Fit 5 25 Muhammad Arif Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 27/07/1999 F.A 21Y,8M,11D yes Sheikhupura Saif Ullah s/o Shoukat Ali 35404-4346815-9 r/o timbi Fit 6 26 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 14/01/1998 F.A 23Y,2M,24D yes Sheikhupura Ehsan Ali s/o Nathha 35404-8753848-1 r/o Tibbi Fit 7 27 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 12/10/1996 B.A 24Y,5M,26D yes Sheikhupura Muhammad Faisal s/o 35404-1572400-7 r/o Bhandor Fit 8 28 Muhammad Aslam PO same Farooqaba Distt: sheikhupura 07/01/1999 Matric 22Y,3M,0D yes Sheikhupura Sunny Ameen s/o 35404-8494036-9 -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The ‘Creole Indian’ The emergence of East Indian civil society in Trinidad and Tobago, c.1897-1945 Kissoon, Feriel Nissa Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 THE ‘CREOLE INDIAN’: THE EMERGENCE OF EAST INDIAN CIVIL SOCIETY IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO, c.1897-1945 by Feriel Nissa Kissoon A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College, University of London London, United Kingdom June 2014 1 ABSTRACT Between 1838 when slavery ended, and 1917, some 143,939 Indians came to Trinidad as indentured labourers. -

Estimates of Charged Expenditure and Demands for Grants (Development)

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB ESTIMATES OF CHARGED EXPENDITURE AND DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (DEVELOPMENT) VOL - II (Fund No. PC12037 – PC12043) FOR 2020 - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Demand # Description Pages VOLUME-I PC22036 Development 1 - 968 VOLUME-II PC12037 Irrigation Works 1 - 49 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 51 - 294 PC12042 Government Buildings 295-513 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities / Autonomous Bodies, etc. 515-529 GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB GENERAL ABSTRACT OF DISBURSEMENT (GROSS) (Amount in million) Budget Revised Budget Estimates Estimates Estimates 2019-2020 2019-2020 2020-2021 PC22036 Development 255,308.585 180,380.664 256,801.600 PC12037 Irrigation Works 25,343.061 18,309.413 18,067.690 PC12041 Roads and Bridges 35,000.000 41,510.013 29,820.000 PC12042 Government Buildings 34,348.354 14,827.803 32,310.710 PC12043 Loans to Municipalities/Autonomous Bodies etc. 76,977.253 28,418.359 29,410.759 TOTAL :- 426,977.253 283,446.252 366,410.759 Current / Capital Expenditure detailed below: New Initiatives of SED for imparting Education through (5,000.000) - (4,000.000) Outsourcing of Public Schools (PEIMA) New Initiatives of SED for imparting Education through (19,500.000) - (18,000.000) Private Participation (PEF) Daanish School and Centres of Excellence Authority (1,500.000) - (1,000.000) Punjab Education Endowment Funds (PEEF) (300.000) - (100.000) Punjab Higher Education Commission (PHEC) (100.000) - (50.000) Establishment of General Hospital at Turbat, Baluchistan - - (50.000) Pakistan Kidney & Liver Institute and Research Center (500.000) - -

Pronunciation

PRONUNCIATION Guide to the Romanized version of quotations from the Guru Granth Saheb. A. Consonants Gurmukhi letter Roman Word in Roman Word in Gurmukhi Meaning Letter letters using the letters using the relevant letter relevant letter from from the second the first column column S s Sabh sB All H h Het ihq Affection K k Krodh kroD Anger K kh Khayl Kyl Play G g Guru gurU Teacher G gh Ghar Gr House | ng Ngyani / gyani i|AwnI / igAwnI Possessing divine knowledge C c Cor cor Thief C ch Chaata Cwqw Umbrella j j Jahaaj jhwj Ship J jh Jhaaroo JwVU Broom \ ny Sunyi su\I Quiet t t Tap t`p Jump T th Thag Tg Robber f d Dar fr Fear F dh Dholak Folk Drum x n Hun hux Now q t Tan qn Body Q th Thuk Quk Sputum d d Den idn Day D dh Dhan Dn Wealth n n Net inq Everyday p p Peta ipqw Father P f Fal Pl Fruit b b Ben ibn Without B bh Bhagat Bgq Saint m m Man mn Mind X y Yam Xm Messenger of death r r Roti rotI Bread l l Loha lohw Iron v v Vasai vsY Dwell V r Koora kUVw Rubbish (n) in brackets, and (g) in brackets after the consonant 'n' both indicate a nasalised sound - Eg. 'Tu(n)' meaning 'you'; 'saibhan(g)' meaning 'by himself'. All consonants in Punjabi / Gurmukhi are sounded - Eg. 'pai-r' meaning 'foot' where the final 'r' is sounded. 3 Copyright Material: Gurmukh Singh of Raub, Pahang, Malaysia B. -

State Capacity in Punjab's Local Governments

Final report State capacity in Punjab’s local governments Benchmarking existing deficits Gharad Bryan Ali Cheema Ameera Jamal Adnan Khan Asad Liaqat Gerard Padro i Miquel June 2019 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: S-37433-PAK-2 STATE CAPACITY IN PUNJAB’S LOCAL GOVERNMENTS: BENCHMARKING EXISTING DEFICITS Gharad Bryan, Ali Cheema, Ameera Jamal, Adnan Khan, Asad Liaqat Gerard Padro i Miquel This Version: August 2019 Abstract As the developing world urbanizes, there is increasing pressure to provide local public goods and local governments are expected to play an important role in their provision. However, there is little work on the nature of of capacity deficits faced by local governments and whether these deficits are acting as a constraint on performance. We use financial accounts data from Punjab’s local governments for 2018-19 to measure their ability to utilize budgets and find that there is considerable variation in this metric across local governments. We supplement this with a management survey with the top managers whose decisions affect budget utilization in a random sample of 129 out of 193 urban local governments in Punjab. We find that the capacity deficits in local governments are particularly challenging in terms of human resource capabilities, the adoption of automated systems, and legal and enforcement capacity. We also find that better human resource capabilities and the use of managerial incentives are positively correlated with budget utilization. Our evidence provides new insights on the importance of management and human resource capabilities and systems capacity in local governments in a developing country setting. -

Towards a Comparative Poetics of Buddha, Kabir and Guru Nanak: Aparna Lanjewar Bose from a Secular Democratic Perspective

Towards a Comparative poetics of Buddha, Kabir and Guru Nanak: Aparna Lanjewar Bose From A Secular Democratic perspective Artículos atravesados por (o cuestionando) la idea del sujeto -y su género- como una construcción psicobiológica de la cultura. Articles driven by (or questioning) the idea of the subject -and their gender- as a cultural psychobiological construction Vol. 4 (2), 2019, abril-septiembre ISSN 2469-0783 https://datahub.io/dataset/2019-4-2-e85 TOWARDS A COMPARATIVE POETICS OF BUDDHA, KABIR AND GURU NANAK: FROM A SECULAR DEMOCRATIC PERSPECTIVE HACIA UNA POÉTICA COMPARATIVA DE BUDA, KABIR Y GURÚ NANAK DESDE UNA PERSPECTIVA DEMOCRÁTICA SECULAR Aparna Lanjewar Bose [email protected] Department of English Literature, School of Literary Studies at The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad, India Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Bose A. L. (2019). «Towards a Comparative poetics of Buddha, Kabir and Guru Nanak: From A Secular Democratic perspective». Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 4(2) abril-septiembre 2019, 19-44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.32351/rca.v4.2.85 Copyright: © 2019 RCAFMC. Este artículo de acceso abierto es distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Recibido: 27/05/2019. Aceptado: 03/06/2019 Publicación online: 30/10/2019 Conflict of interests: None to declare. Abstract This article shows how democratic secular values existed 2500 years ago with the Buddha and later during the saint tradition in India, around 14th and 15th century, with Kabir and Guru Nanak even before they were legalized and enshrined in the Indian constitution. -

Sacrifice at Hazur Sahib Myth & Truth

world sikh news 12 Jan 21-27, 2009 U N T A N G L I N G A M Y T H Sacrifice at Hazur Sahib Myth & Truth A veteran Deccani Sikh himself, the author presents the facts of the honour of weapons at Hazur Sahib and calls for caution in its condemnation. He clears the air over the vegetarian-non-vegetarian debate amongst Sikhs and seeks effective steps to rid Sikh society of unethical and unSikh practices wherever they are practiced. World Sikh News presents these facts, not to foment the debate, but to help build a hypothesis for solution to this never-ending debate for the benefit of a wider cross-section of the Sikh people. he Internet has provid- Nanak Singh Nishter Guru Gobind Singh Ji in the year in fire for performing Havan, ed a forum for free 1708. Around 1830, the Sikh Army Yagyan, Lohri and other such fes- speech which is being understanding the details of the of Maharaja Ranjit Singh came to tivities. abused by all and phenomenon. help the Nizam, who was the ruler On page number 1275 of Guru sundry to project their Beyond all reasonable doubt let of Hyderabad. This army was Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak Sahib views with the finality me authoritatively say and explain retained here as a Sikh Peace keep- has further explained the law of Tof an intellectual whose research how this myth is a half-truth and ing Force, which had 14 Risalas nature that, "Ek ji, kai jiyaan cannot be wrong. All writers, more injurious than the lie. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Provincial Assembly Polling Scheme

FORM-28 [see rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY National Assembly Election to the *Provincial Assembly of the Punjab No. and name of constituency PP-135-Sheikhupura-I S. No. of Voters Number of Voters assigned to In case of rural areas In Case of Urban Area Number of Polling Booths on the Electoral polling Station No. and Name of Polling Sr. No roll in case Station Census Block Census Block Name of electoral area Name of Electoral Area electoral area is Male Female Total Male Female Total Code Code bifurcated 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Mohallah Pir Bhukhari 199060101 402 0 402 1. Government.Boys High Mohallah Sharif Pura 199060102 566 0 566 1 School Ferozeabad 4 0 4 Mohallah Muzafrabad 199060103 343 0 343 Narang(Male) (P)* Sadar Bazar No.1 199060104 338 0 338 2. Government.Boys High Sadar Bazar No.2 199060105 462 0 462 2 School Ferozeabad Narang Sadar Bazar No.3 199060201 491 0 491 3 0 3 (Male) (P)* Sadar Bazar No.4 199060202 452 0 452 3. Government.Boys High Sadar Bazar No.5 199060203 372 0 372 3 School Ferozeabad Narang Mohallah Muzafrabad 199060204 413 0 413 2 0 2 (Male) (P)* Sadar Bazar No.6 199060205 486 0 486 Mohallah Pir Bhukhari 199060101 0 317 317 4. Government.Boys High Mohallah Sharif Pura 199060102 0 412 412 4 School Mandarwala Sadar 0 2 2 Mohallah Muzafrabad 199060103 0 280 280 Bazar Narang. (Female) (P)* Sadar Bazar No.1 199060104 0 303 303 5.