State Capacity in Punjab's Local Governments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Transformation in the District of Sheikhupura, 1849-1947

Iram Naseer Ahmad* COLONIAL TRANSFORMATION IN THE DISTRICT OF SHEIKHUPURA, 1849-1947 Abstract This research paper analyses the British colonial transformation in the district of Sheikhupura. The geographical, revenue, judicial and administrative changes have been understood in the sense of establishing a controlled society in the district. This paper sheds light on colonial changes in the district of Sheikhupura under the British raj from 1857 to 1947. The phenomenon of introducing a new administrative and revenue mechanism in Sheikhupura was a project that was not detached from imperialistic ambitions and designs of colonial power in whole of India. The new colonial administrative system, including the reorganization and demarcation of boundaries and setting up centralized administrative machinery particularly a strong revenue, police, and judicial system. Ironically, it was devised to effectively protect the “world monopoly of industrial production” in the British India. It was enforced effectively by a reconstitution of the power structure of the land which meant search for new allies. At the end the article examines the origin of new towns and tehsils in Sheikhupura after the advent of British rule. It observes that British colonialism altered the whole scenario in Sheikhupura which was considered of crucially important for initial colonial control in this district. Keywords: Sheikhupura, British, Imperialism, colonialism The era of British colonialism in the district of Sheikhupura has been divided into three stages. The first stage of colonialism stretches from 1600 to 1757, it deals with the period of monopoly of natural trade and extraction of revenue.1In this stage British traders monopolized the trade with the other European traders as well. -

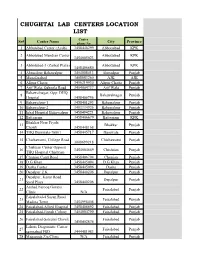

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

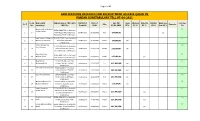

24Th June, 2018 No. NA-138/GE 2018 In

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION 24th June, 2018 No. NA-138/GE 2018 In pursuance of the provisions of Sub-Section 6 of Section 59 of the Elections Act, 2017 (XXXIII of 2017) read with Sub-Rule 4 of Rule 50 of the Election Rules, 2017, undersigned hereby publishes, for general information of the public, the final list of Polling Stations in respect of National Assembly Constituency No. NA-138 Kasur-II for conduct of General Elections, 2018. By order of the Election Commission of Pakistan &((e5 JU DISTRICT RETURNING OFFICER KASUR ABSRACT OF FINAL LIST OF POLLING SCHEME STATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY NA 138 KASUR-II NO & NAME OF NO.POLLING STATIONS NO.OF VOTES NO.OF POLLING BOOTHS SR CONSTITUENCY MALE FEMALE COMBINED TOTAL MALE FEMALE TOTAL MALE FEMALE TOTAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 NA-138 111 95 132 338 246580 181025 427605 544 414 958 KASUR-II A.PPR()VE.9 RAFAQAT ALI QAMAR Returning Officer, saijac-i Officer, NA-138 Kasur-II Ka Rafarit (7arnar Return. h1A FORM 28 [see rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY NA-138- KASUR-II Sr. Sr. No & Name of the In case of Rural Areas In case of Urban Areas Sr. No. of voters No. of Voters No. Polling Station on the Electoral Assigned to Polling No. of Polling Booths Rolls in case of bifurcation of Male Female Name of Electoral area Census Block Name of Electoral area Census Electoral Area Male Female Total code Block code 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 Govt. -

Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited

LAHORE ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LIMITED OOFICE OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER LESCO HEAD OFFICE22-A QUEENS ROAD LAHORE Phone # 99204801 Fax # 99204803 E-MAIL : [email protected] No.3957/FD/LESCO/CPC/Tariff 2013-14 Dated Jul 04, 2013 The Registrar NEPRA 2" Floor OPD Building, G-5/2 Islamabad. Subject: PETITION FOR DETERMINATION OF CONSUMER END TARIFF FOR FY 2013-14 Enclosed please find the Petition for Determination of Revenue Requirement and Consumer End Tariff for FY 2013-14. The Authority is requested in order to recover the revenue requirement in time the proposed tariff be allowed so that the same may be applicable from Jul 01, 2013 subject to an order for refund for the protection of consumers during the pendency of this petition in terms of Sub-Rule 7 of Rule 4 of NEPRA (Tariff Standards and Procedures) Rules, 1998. Regards, Muhamm d Saleem Chief Ex utive Officer LESCO Enclosed Please find: 1. Tariff Petition for FY 2013-14. 2. Standardized Tariff Petition Formats. 3. Demand Draft of Rs:- 7,760 Bearing No. fated PAKISTAN AFFIDAVIT I, Muhammad Saleem, Chief Executive Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited, (Distribution License # 03/DL/2002 dated April 01,2002) being duly authorized representative/attomey of Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited, hereby solemnly affirm and declare that the contents of the accompanying petition/application # 3957/FD/LESCO/CPC/Tariff 2013-14 dated July 04, 2013, including all supporting documents are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief and that nothing has been concealed. I also affirm that all further documentation and information to be provided by me in connection with the accompanying petition shall be true to the best of my knowledge and belief. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Applications Received for Recruitment As Naib Qasid in Punjab Constabulary Till 07-04-2021

Page 1 of 85 APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR RECRUITMENT AS NAIB QASID IN PUNJAB CONSTABULARY TILL 07-04-2021 Form Name with Address as per CNIC with District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. # Edu: Remarks No. parentage CNIC No. Domicile Birth 07-04-2021 57% 15 % 05 % 03 % Son 20 % Fit Muhammad Tallat Bhatti Fit 35404-5665873-5 r/o Muhallah s/o Amanullah 1 3 Makki Nagar Mureedkey road Sheikhupura 01/08/2002 FSC 18Y,8M,6D yes Farooqabad Distt: sheikhupura Syed Usman Ali Shah s/o 35404-8415306-5 r/o Chak Wahi Fit 2 4 Mazhar Hussain Shah No.522 PO same Distt: Sheikhupura 01/04/2003 Matric 18Y,0M,6D yes sheikhupura Nabeel Shakoor s/o Fit 35404-8509339-3 r/o Muhallah Abdul Shakoor 3 10 Christian Basti near Church Sheikhupura 07/02/1998 Middle 23Y,2M,0D yes Farooqabad Distt: Sheikhupura Akash Masih s/o Fit 35404-0663146-5 r/o Esa Nagri 4 20 Mukhtar Masih sheikhupura 05/12/1999 Middle 21Y,4M,2D yes road Chhapa road Sheikhupura Majid Ali s/o 35404-3285488-7 r/o Tibbi Fit 5 25 Muhammad Arif Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 27/07/1999 F.A 21Y,8M,11D yes Sheikhupura Saif Ullah s/o Shoukat Ali 35404-4346815-9 r/o timbi Fit 6 26 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 14/01/1998 F.A 23Y,2M,24D yes Sheikhupura Ehsan Ali s/o Nathha 35404-8753848-1 r/o Tibbi Fit 7 27 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 12/10/1996 B.A 24Y,5M,26D yes Sheikhupura Muhammad Faisal s/o 35404-1572400-7 r/o Bhandor Fit 8 28 Muhammad Aslam PO same Farooqaba Distt: sheikhupura 07/01/1999 Matric 22Y,3M,0D yes Sheikhupura Sunny Ameen s/o 35404-8494036-9 -

List of Canidates for Recuritment of Mali at Police College Sihala

LIST OF CANIDATES FOR RECURITMENT OF MALI AT POLICE COLLEGE SIHALA not Sr. No Sr. Name Address CNIC No CNIC age on07-04-21age Remarks Attached Qulification Date ofBirth Date Father Name Father Appliedin Quota AppliedPost forthe Date ofTestPractical Date Home District-DomicileHome Affidavit attached / Not Not Affidavit/ attached Day Month Year Experienceor Certificate attached 1 Ghanzafar Abbas Khadim Hussain Chak Rohacre Teshil & Dist. Muzaffargarh Mali Open M. 32304-7071542-9 Middle 01-01-86 7 4 35 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 W. No. 2 Mohallah Churakil Wala Mouza 2 Mohroz Khan Javaid iqbal Pirhar Sharqi Tehsil Kot Abddu Dist. Mali Open M. 32303-8012130-5 Middle 12-09-92 26 7 28 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Muzaffargarh Ghulam Rasool Ward No. 14 F Mohallah Canal Colony 3 Muhammad Waseem Mali Open M. 32303-6730051-9 Matric 01-12-96 7 5 24 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Khan Tehsil Kot Addu Dist. Muzaffargrah Muhammad Kamran Usman Koryia P-O Khas Tehsil & Dist. 4 Rasheed Ahmad Mali Open M. 32304-0582657-7 F.A 01-08-95 7 9 25 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Rasheed Muzaffargrah Muhammad Imran Mouza Gul Qam Nashtoi Tehsil &Dist. 5 Ghulam Sarwar Mali Open M. 32304-1221941-3 Middle 12-04-88 26 0 33 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Sarwar Muzaffargrah Nohinwali, PO Sharif Chajra, Tehsil 7 6 Mujahid Abbas Abid Hussain Mali Open M. 32304-8508933-9 Matric 02-03-91 6 2 30 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 District Muzaffargarh. Hafiz Ali Chah Suerywala Pittal kot adu, Tehsil & 7 Muhammad Akram Mali Disable 32303-2255820-5 Middle 01-01-82 7 4 39 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Mumammad District Muzaffargarh. -

The Partition of India Midnight's Children

THE PARTITION OF INDIA MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN, MIDNIGHT’S FURIES India was the first nation to undertake decolonization in Asia and Africa following World War Two An estimated 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of India Partition saw the largest migration of humans in the 20th Century, outside war and famine Approximately 83,000 women were kidnapped on both sides of the newly-created border The death toll remains disputed, 1 – 2 million Less than 12 men decided the future of 400 million people 1 Wednesday October 3rd 2018 Christopher Tidyman – Loreto Kirribilli, Sydney HISTORY EXTENSION AND MODERN HISTORY History Extension key questions Who are the historians? What is the purpose of history? How has history been constructed, recorded and presented over time? Why have approaches to history changed over time? Year 11 Shaping of the Modern World: The End of Empire A study of the causes, nature and outcomes of decolonisation in ONE country Year 12 National Studies India 1942 - 1984 2 HISTORY EXTENSION PA R T I T I O N OF INDIA SYLLABUS DOT POINTS: CONTENT FOCUS: S T U D E N T S INVESTIGATE C H A N G I N G INTERPRETATIONS OF THE PARTITION OF INDIA Students examine the historians and approaches to history which have contributed to historical debate in the areas of: - the causes of the Partition - the role of individuals - the effects and consequences of the Partition of India Aims for this presentation: - Introduce teachers to a new History topic - Outline important shifts in Partition historiography - Provide an opportunity to discuss resources and materials - Have teachers consider the possibilities for teaching these topics 3 SHIFTING HISTORIOGRAPHY WHO ARE THE HISTORIANS? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF HISTORY? F I E R C E CONTROVERSY HAS RAGED OVER THE CAUSES OF PARTITION. -

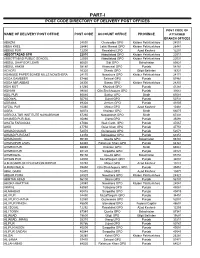

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Short Tender Notice

SHORT TENDER NOTICE Sealed tenders based on item market rates schedule of the MRS 1 st Bi-Annual 2020 (1 st January2020 to 30 th June 2020) District Mianwali are hereby invited for the works mentioned below from the eligible Contractors/Firms enlisted/renewed for the year 2019-20 with Public Health Engineering Department as well as registered with Punjab Revenue Authority (PRA). Tender request should be accompanied with Original Enlistment Letter/up to date Renewal letter, Fee Receipt, P.E.C License for 2019-20 and copy of C.N.I.C. Authority letter on Original pad Form of the Contractor/ Firm along with registered partnership deed, attested power of Attorney on stamp paper along with prescribed tender fee. The tender/bidding documents are available and will be issued by the Divisional Head Clerk of this office upto 29-06-2020 during the office hours on production of paid 32-A Challan form of tender fee deposited in National Bank of Pakistan Mianwali paid on or before 26-06-2020. Tender rates and amounts should be filled in figures as well as in words. Tender should be signed as per general direction given in the tender documents. Tender will be received in the office of Commissioner Sargodha Division Sargodha up to 02:00 PM on the date of receiving of tenders and will be opened after 30 minutes by the Tender Committee in the presence of intending contractors or their representatives. Tenders / bids received by post or through any other means shall not be maintained. The conditional, incomplete and over written tender / bids will be rejected. -

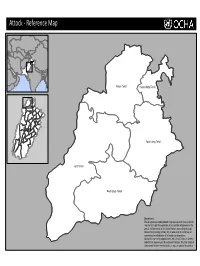

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Field Appraisal Report Tma Ferozewala

FIELD APPRAISAL REPORT TMA FEROZEWALA Prepared by; Punjab Municipal Development Fund Company December-2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 1.1 BACKGROUND 2 1.2 METHODOLOGY 2 1.3 DISTRICT PROFILE 2 1.3.1 History 2 1.3.2 Location 2 1.3.3 Area/Demography 2 1.4 TMA/TOWN PROFILE 3 1.4.1 TMA Status 3 1.4.2 Location 3 1.4.3 Area / Demography 3 1.5 TMA STAFF PROFILE 4 1.6 INSTITUTIONAL ASSESSMENT 4 1.6.1 Tehsil Nazim 4 1.6.2 Office of Tehsil Municipal Officer 4 1.7 TEHSIL OFFICER (Planning) OFFICE 8 1.8 TEHSIL OFFICER (Regulation) OFFICE 10 1.9 TEHSIL OFFICER (Finance) OFFICE 11 1.10 TEHSIL OFFICER (Infrastructure & Services) OFFICE 15 2. INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 2.1 ROADS 17 2.2 WATER SUPPLY 17 2.3 SEWERAGE 18 2.4 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT 18 2.5 FIRE FIGHTING 18 2.6 PARKS 18 1 1. INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 1.1 BACKGROUND TMA Ferozewala has applied for funding under PMSIP. After initial desk appraisal, PMDFC field team visited the TMA for assessing its institutional and engineering capacity. 1.2 METHODOLOGY Appraisal is based on interviews with TMA staff, open-ended and close-ended questionnaires and agency record. Debriefing sessions and discussions were held with Tehsil Nazim, TMO, TOs and other TMA staff. 1.3 DISTRICT PROFILE 1.3.1 History The district of Sheikhupura derives its name from its headquarters town, which was named after the Emperor Jehangir, who founded it and was called by nickname of Sheikhu by his father.