AGREEMENT and INCORPORATION in ATHABASKAN and in GENERAL Ken Hale, MIT 0. Introduction. in Many Languages of the World, the Verb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parameters and Micro-Parameters in Arabic Sentence Structure

PARAMETERS AND MICRO-PARAMETERS IN ARABIC SENTENCE STRUCTURE By Kemel Jouini A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Victoria University of Wellington 2014 ACKNOWLEGDMENTS I would like to thank Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, in particular, for accepting to be my adviser for the nine-month period I spent at the Department of Linguistics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the academic year 2004-2005 as a non- degree Fulbright grantee. During my stay at UIUC, Elabbas’s lectures convinced me of the view that a proper understanding of the feature structure of functional categories could enlighten linguistic theory on how the structure of sentences could vary cross-linguistically. Special thanks go to Dr. Elizabeth Pearce for willing to be my supervisor, for her patience to read through the so many drafts of chapters I was sending her, and for her advice on the numerous revisions I thereby had to make. I also thank Professor Richard S. Kayne for the invaluable opportunity he offered me during his visit at VUW to discuss with him some aspects of micro- parametric syntax relevant to my analysis of verbal inflection. Last, but not least, I thank my secondary supervisor Dr. Sasha Calhoun for her willingness to share ideas and offer suggestions, as well as Professor Laurie Bauer for his helpful comments on part of my thesis. I also want to thank Professor Tim Stowell, Professor Halldór Sigurðsson, Professor Henry Davis, Professor Jan Koster and Dr. Fred Hoyt for sending me documents I could not find elsewhere. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, and Resumptionw Relational Nouns, Such As Neighbour, Mother, and Rumour, Present a Challenge to Synt

Linguistics and Philosophy (2005) 28:375–446 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10988-005-2656-7 ASH ASUDEH RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, AND RESUMPTIONw ABSTRACT. This paper presents a variable-free analysis of relational nouns in Glue Semantics, within a Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) architecture. Rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns are bound using the usual binding mecha- nisms of LFG. Special attention is paid to the bound readings of relational nouns, how these interact with genitives and obliques, and their behaviour with respect to scope, crossover and reconstruction. I consider a puzzle that arises regarding rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns, given that relational nouns can have bound readings and resumptive pronouns are just a specific instance of bound pronouns. The puzzle is: why is it impossible for bound implicit arguments of relational nouns to be resumptive? The puzzle is highlighted by a well-known variety of variable-free semantics, where pronouns and relational noun phrases are identical both in category and (base) type. I show that the puzzle also arises for an established variable-based theory. I present an analysis of resumptive pronouns that crucially treats resumptives in terms of the resource logic linear logic that underlies Glue Semantics: a resumptive pronoun is a perfectly ordinary pronoun that constitutes a surplus resource; this surplus resource requires the presence of a resumptive-licensing resource consumer, a manager resource. Manager resources properly distinguish between resumptive pronouns and bound relational nouns based on differences between them at the level of semantic structure. The resumptive puzzle is thus solved. The paper closes by considering the solution in light of the hypothesis of direct compositionality. -

The University of Hull Mutation and the Syntactic Structure Of

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL MUTATION AND THE SYNTACTIC STRUCTURE OF i MODERN COLLOQUIAL WELSH being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by MARGARET OLWEN TALLERMAN B.A. (HONS.) June 1987 -b bLf3 1987 SUMMAR/ Summary of Thesis submitted for PhD degree by Margaret Olwen Tallerman on Mutation and the Syntactic Structure of Modern Colloquial Welsh In this dissertation I discuss the phenomenon of initial consonantal mutation in modern Welsh, and explore the syntactic structure of this language: I will concentrate on the syntax of Colloquial rather than Literary Welsh. It transpires that mutation phenomena can frequently be cited as evidence for or against certain syntactic analyses. In chapter 1 I present a critical survey of previous treatments of mutation, and show that mutation in Welsh conforms to a modified version of the Trigger Constraint proposed by Lieber and by Zwicky. It is argued that adjacency of the mutation trigger is the criterial property in Welsh. Chapter 2 presents a comprehensive description of the productive environments for mutation in modern Welsh. In chapter 3 I give a snort account of Government and Binding theory, the framework used for several recent analyses of Celtic languages. I also discuss proposals that have been made concerning the underlying word order of Welsh, a surface VSO language. Although I reject SVO underlying order, I conclude that there is nonetheless a VP constituent in Welsh. Chapters 4 and 5 concern the role of NPs as triggers for Soft Mutation: both overt and 1 empty category NPs are considered. -

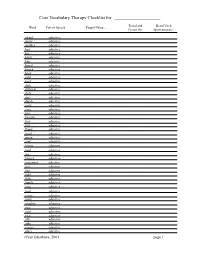

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Contracted Preposition-Determiner Forms in German: Semantics And

Contracted Preposition-Determiner Forms in German: Semantics and Pragmatics A Thesis Presented to the Departament de Traducci´oi Filologia, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Estela Sophie Puig Waldm¨uller Advisor: Dr. Louise McNally Seifert March, 2008 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Contexts where NCFs are used or preferred 4 2.1 Introduction . 5 2.2 Basic assumptions on the use of definite NPs in German . 5 2.2.1 Anaphoric use . 9 2.2.2 Endophoric use . 10 2.2.3 Generic use . 11 2.2.4 Use with inferable referents . 12 2.2.5 Use with “inherently” unique expressions . 14 2.3 NCFs as anaphoric definites . 15 2.4 NCFs as endophoric definites . 20 2.4.1 Restrictive relative clauses . 20 2.4.2 Restrictive modifiers . 22 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii 2.5 NCFs with inferable referents (“Bridging”) . 23 2.6 Summary . 25 3 Contexts where CFs are used or preferred 26 3.1 Introduction . 27 3.2 Overview . 27 3.3 CFs with semantically unique expressions . 31 3.3.1 “Head-Noun-Driven” uniqueness . 31 3.3.1.1 Proper nouns . 31 3.3.1.2 Time and Date expressions . 34 3.3.1.3 Abstract expressions . 35 3.3.1.4 Situationally unique individuals . 37 3.3.2 “Modifier-Driven” uniqueness: Superlatives and or- dinals . 41 3.4 CFs with non-specific readings . 42 3.4.1 Relational use . 43 3.4.2 Situational use (“Configurational use”) . 44 3.4.3 Idiomatic use . -

Overt Pronouon Constraint Effects in Second Lanugage Japanese

Overt Pronoun Constraint effects in second language Japanese Tokiko Okuma Department of Linguistics McGill University Montreal, Quebec April 2, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Tokiko Okuma 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the applicability of the Full Transfer/Full Access hypothesis (FT/FA) (Schwartz & Sprouse, 1994, 1996) by investigating the interpretation of the Japanese pronoun (kare ‘he’) by adult English and Spanish speaking learners of Japanese. The Japanese, Spanish, and English languages differ with respect to interpretive properties of pronouns. In Japanese and Spanish, overt pronouns disallow a bound variable interpretation in subject and object positions. By contrast, In English, overt pronouns may have a bound variable interpretation in these positions. This is called the Overt Pronoun Constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti, 1984). The FT/FA model suggests that the initial state of L2 grammar is the end state of L1 grammar and that the restructuring of L2 grammar occurs with L2 input. This hypothesis predicts that L1 English speakers of L2 Japanese would initially allow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions, transferring from their L1s. Nevertheless, they will successfully come to disallow a bound variable interpretation as their proficiency improves. In contrast, L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese would correctly disallow a bound variable interpretation of Japanese pronouns in subject and object positions from the beginning. In order to test these predictions, L1 English and L1 Spanish speakers of L2 Japanese at intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency were compared with native Japanese speakers in their interpretations of pronouns with quantified i antecedents in two tasks. -

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian

Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian DAVID H. PENTLAND University of Manitoba In his comparative Algonquian sketch, Bloomfield (1946) distinguished three classes of words: nouns, verbs, and particles. Within the particle category he further distinguished pronouns (subdivided into personal pro nouns, demonstratives, indefinite pronouns, and interrogative pronouns), preverbs (defined as particles which freely precede verb stems, including some particles which never occur anywhere else), and prenouns (particles which similarly appear before nouns). Other scholars have found it useful to set up separate word classes of pronouns and numerals (e.g., Goddard & Bragdon 1988, Nichols & Nyholm 1995), and nowadays most Algonquianists treat preverbs and their kin as a separate category, rather than as a sub-class of particles. Beyond this there is little agreement. For example, in his sketch of Malecite-Passamaquoddy, Teeter (1971:203) divided the words we are concerned with into the categories prenoun, preverb and adverb - the last roughly equivalent to Bloom- field's particle. LeSourd (1993:8) more closely followed Bloomfield in stating that there are only three parts of speech, noun, verb and particle, but went on to note that there are also "loosely joined modifiers known as preverbs and prenouns" (LeSourd 1993:16) which may precede verb stems and noun stems, though he does not seem to have defined "modifier" in rela tion to the parts of speech. Leavitt (1985) introduced a distinction between "separate" preverbs and "attached" preverbs. However, in practice his "separate" preverbs include not only what others call preverbs, but also initial elements (i.e., "attached preverbs") which happen to be followed by an HI in derivation. -

לפני; של; תוך; בלעדי; אל :Confusables • • Less Commonly Used Prepositions (Appendix)

8. PREPOSITIONS מילות יחס This chapter discusses: • The formal characteristics of the prepositions (section 1) • The meanings of the prepositions (section 2) • The use of prepositions within the sentence (section 3) ליד; לפי; לפני; של; תוך; בלעדי; אל :Confusables • • Less commonly used prepositions (Appendix) This chapter will help the reader to: • Distinguish between translatable and non-translatable prepositions • Choose the correct translation for prepositions with multiple meanings are definite or indefinite ב,כ,ל Determine whether nouns preceded by the prepositions • • Identify the reference of inflected prepositions in relative clauses • Use prepositions as an aid in reading comprehension 298 . prepositions Prepositions: an overview Prepositions link verbs, nouns and adjectives to nouns. Unlike Hebrew nouns, verbs and adjec- tives, prepositions have no number or gender markings. The preposition may be attached to merge ל- and כ- ,ב -the noun or stand on its own as an independent word. The prepositions .ה -with the definite article In Hebrew, a preposition cannot be followed by a pronoun – instead, it is inflected with the appropriate pronoun suffix. Some prepositions have a fixed meaning and are, therefore, translatable into English. Others – usually those that are required by the verb and as such are considered part of it (in fact, the preposition may change the meaning of the verb) – may be ignored in translation, or may have different translation options in different linguistic environments. 1. The forms of the prepositions The