Questions of Modernity and Postcoloniality in Modern Indian Theatres: Problems and Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

Global Feminisms: Interview Transcripts: India Language: English

INDIA Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship Interview Transcripts: India Language: English Interview Transcripts: India Contents Acknowledgments 3 Shahjehan Aapa 4 Flavia Agnes 23 Neera Desai 48 Ima Thokchom Ramani Devi 67 Mahasweta Devi 83 Jarjum Ete 108 Lata Pratibha Madhukar 133 Mangai 158 Vina Mazumdar 184 D. Sharifa 204 2 Acknowledgments Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan (UM) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The project was co-directed by Abigail Stewart, Jayati Lal and Kristin McGuire. The China site was housed at the China Women’s University in Beijing, China and directed by Wang Jinling and Zhang Jian, in collaboration with UM faculty member Wang Zheng. The India site was housed at the Sound and Picture Archives for Research on Women (SPARROW) in Mumbai, India and directed by C.S. Lakshmi, in collaboration with UM faculty members Jayati Lal and Abigail Stewart. The Poland site was housed at Fundacja Kobiet eFKa (Women’s Foundation eFKa) in Krakow, Poland and directed by Slawka Walczewska, in collaboration with UM faculty member Magdalena Zaborowska. The U.S. site was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan and directed by UM faculty member Elizabeth Cole. Graduate student interns on the project included Nicola Curtin, Kim Dorazio, Jana Haritatos, Helen Ho, Julianna Lee, Sumiao Li, Zakiya Luna, Leslie Marsh, Sridevi Nair, Justyna Pas, Rosa Peralta, Desdamona Rios and Ying Zhang. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

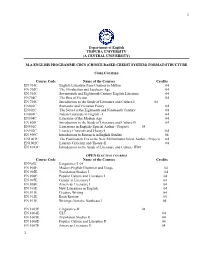

Ma English Programme Cbcs (Choice Based Credit System)

1 Department of English TRIPURA UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) M.A ENGLISH PROGRAMME CBCS (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FORMAT/STRUCTURE CORE COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits EN 701C English Literature from Chaucer to Milton 04 EN 702C The Elizabethan and Jacobean Age 04 EN 703C Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century English Literature 04 EN704C The Rise of Fiction 04 EN 705C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture-I 04 EN801C Romantic and Victorian Poetry 04 EN802C The Novel in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century 04 EN803C Indian Literature in English - I 04 EN804C Literature of the Modern Age 04 EN 805C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture-II 04 EN901C Literatures in English (Special Author - Project) 04 EN902C Literacy Criticism and Theory-I 04 EN 909C Introduction to Research in English Studies 04 EN1001C The Postmodern Era to the New Millennium (Select Author - Project) 04 EN1002C Literary Criticism and Theory-II 04 EN 1013C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture- III04 OPEN ELECTIVE COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits EN903E Linguistics-I 04 EN 904E Modern English Grammar and Usage 04 EN 905E Translation Studies I 04 EN 906E Popular Culture and Literature I 04 EN 907E Gender in Literature I 04 EN 908E American Literature I 04 EN 910E New Literatures in English 04 EN 911E Creative Writing 04 EN 912E Book Review 04 EN 913E Writings from the Northeast I 04 EN 1003E Linguistics-II 04 EN 1004E ELT 04 EN 1005E Translation Studies II 04 EN 1006E Popular Culture and Literature II 04 EN 1007E American Literature II 04 1 2 EN 1008E Literature and Industry 04 EN 1009E Folk and Oral Literatures 04 EN 1010E Writings from the Northeast II 04 EN 1011E New Literatures in English II 04 EN 1012E Gender in Literature II 04 COMPULSORY FOUNDATION COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits Basics of Computer Applications Skill I 04 Seminar Presentation (No End-semester examination. -

History and Political Science

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 29.12.2017 and it has been decided to implement it from the educational year 2018-19. HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE STANDARD TEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune. The digital textbook can be obtained through DIKSHA App on a smartphone by using the Q. R. Code given on title page of the textbook and useful audio-visual teaching-learning material of the relevant lesson will be available through the Q. R. Code given in each lesson of this textbook. First Edition : 2018 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Reprint : Research, Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves October 2020 all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee Authors History Political Science Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre, Member Translation Scrutiny Dr Somnath Rode, Member Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Manjiri Bhalerao Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Dr Sanjot Apte Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Cover and Illustrations Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Shri. Devdatta Prakash Balkawade Typesetting Civics Subject Committee DTP Section, Balbharati Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Paper Prof. -

TIWARI-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Bhavya Tiwari 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Bhavya Tiwari Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South Committee: Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Supervisor David Damrosch Martha Ann Selby Cesar Salgado Hannah Wojciehowski Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South by Bhavya Tiwari, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication ~ For my mother ~ Acknowledgements Nothing is ever accomplished alone. This project would not have been possible without the organic support of my committee. I am specifically thankful to my supervisor, Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, for giving me the freedom to explore ideas at my own pace, and for reminding me to pause when my thoughts would become restless. A pause is as important as movement in the journey of a thought. I am thankful to Martha Ann Selby for suggesting me to subhead sections in the dissertation. What a world of difference subheadings make! I am grateful for all the conversations I had with Cesar Salgado in our classes on Transcolonial Joyce, Literary Theory, and beyond. I am also very thankful to Michael Johnson and Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski for patiently listening to me in Boston and Austin over luncheons and dinners respectively. I am forever indebted to David Damrosch for continuing to read all my drafts since February 2007. I am very glad that our paths crossed in Kali’s Kolkata. -

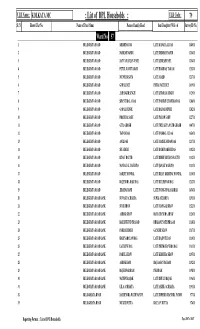

List of BPL Households : ULB Code : 79 Sl

ULB Name : KOLKATA MC : List of BPL Households : ULB Code : 79 Sl. N House/ Flat No. Name of Para/ Slum Name of family Head Son/ Daughter/ Wife of Survey ID No. o Ward No 57 1 BELEGHATA ROAD KRISHNA DAS LATE KANAI LAL DAS 1440 R 2 BELEGHATA ROAD NARESH NANDI LATE DEBRAM NANDI 1236 R 3 BELEGHATA ROAD SATYA RANJAN PAUL LATE SURESH PAUL 1234 R 4 BELEGHATA ROAD PUTUL RANI TARAM LATE HARIDAS TARAM 1232 R 5 BELEGHATA ROAD MUNNI BEGUM LATE MAJID 1217 R 6 BELEGHATA ROAD GOPAL DEY PRIYA NATH DEY 1439 R 7 BELEGHATA ROAD JAHANGIR SINGH LATE SITARAM SINGH 1129 R 8 BELEGHATA ROAD SHANTI BALA DAS LATE NARESH CHANDRA DAS 1248 R 9 BELEGHATA ROAD GOPAL DENRE LATE BADAL DENRE 1242 R 10 BELEGHATA ROAD PRATIMA SAHU LATE PARAN SAHU 1227 R 11 BELEGHATA ROAD GITA GHOSH LATE TRILAKYA NATH GHOSH 1447 R 12 BELEGHATA ROAD TAPAN DAS LATE NANDALAL DAS 1450 R 13 BELEGHATA ROAD ANIL DAS LATE MADHUSUDAN DAS 1237 R 14 BELEGHATA ROAD SITA DEBI LATE RAMPRABESH DAS 1182 R 15 BELEGHATA ROAD BINAY RAUTH LATE BIDHU BHUSAN RAUTH 1132 R 16 BELEGHATA ROAD NANDALAL MAHATO LATE JANAK MAHATO 1131 R 17 BELEGHATA ROAD SARJIT MONDAL LATE BIJAY KRISHNA MONDAL 1130 R 18 BELEGHATA ROAD RAJENDRA RABI DAS LATE KULESWAR DAS 1212 R 19 BELEGHATA ROAD JHARNA RANI LATE NANIGOPAL SARKAR 1456 R 20 BELEGHATA ROAD LANE SUVASH ACHARYA SUNIL ACHARYA 1193 R 21 BELEGHATA ROAD LANE SUMI SHAW LATE MANGAL SHAW 1322 R 22 BELEGHATA ROAD LANE ASHOK SHAW RAM CHANDRA SHAW 1320 R 23 BELEGHATA ROAD LANE BALMUKUND PRASAD DHARAM NATH PRASAD 1318 R 24 BELEGHATA ROAD LANE PARBATI DEBI GANESH SHAW 1317 R 25 BELEGHATA -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 16th of July, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL , CHIEF JUSTICE (ACTING) ( ) HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI On 16-07-2021 1 (Larger 1 HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON Bench) HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 16-07-2021 2 2 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM MUKHERJEE DB - II At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 16-07-2021 3 6 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB-III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 16 On 16-07-2021 4 67 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 16-07-2021 5 76 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB - V At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 30 On 16-07-2021 6 83 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB-VI At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 16-07-2021 7 88 HON'BLE JUSTICE BISWAJIT BASU DB-VII At 11:00 AM 8 On 16-07-2021 8 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 97 SB II At 11:00 AM 9 On 16-07-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 121 SB - III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 13 On 16-07-2021 10 129 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB At 02:45 PM 13 On 16-07-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 130 SB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI 7 On 16-07-2021 12 157 BHATTACHARYYA SB - V At 11:00 AM 26 On 16-07-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B.