Global Feminisms: Interview Transcripts: India Language: English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Draupadi” and “Behind the Bodice” Anoushka Sinha

Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS) ISSN: 2547-0044 http://ellids.com/archives/2019/10/3.1-Sinha.pdf CC Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License www.ellids.com Resistance as Embodied Experience: A Study of Mahasweta Devi’s “Draupadi” and “Behind the Bodice” Anoushka Sinha Something fearful has happened somewhere. The nation doesn’t know it. (Mahasweta Devi, “Behind the Bodice,” emphasis added) Experience and knowledge might seem interchangeable terms. However, when theoretically examined, they pose a conflicting di- lemma in their respective nature and relation with each other. On one hand, knowledge is primarily derived from experience. The intrinsic characteristic of intimacy and immediacy of any experience catego- rizes it as highly subjective. Knowledge, on the other hand, is catego- rized as objective, pertaining to a certain universal appeal. Hereby arises a schism between the two concepts: experience and knowledge. This paper sets out to interrogate the complex relationship between the two concepts through a critical examination of Mahasweta Devi’s short fiction, “Draupadi” (1981) and “Behind the Bodice” (1996). The protagonists of these stories emerge as agents of resistance as the body becomes a crucial site of embodiment of experience. The complexity of experience and its role in the formation of the subject is explored through the course of this paper. Nation building became a significant enterprise in the forma- tion of the identity of the postcolonial India. This identity was prem- ised upon a certain idea of uniformity which led to the homogenization of the nation’s people into a particular perspective. Such perspective, in modern day liberal democracies, is exercised by the state and its various apparatuses (both repressive as well as ideological) to form a singular notion of the nation based on dominant/majoritarian views, thus stripping off its heterogeneity. -

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

Balika Badhu: a Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Department of Electrical and Computer Publications Engineering 2002 Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Electronics Commons, Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, Optics Commons, Other Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, and the Systems and Communications Commons eCommons Citation Chatterjee, Monish Ranjan, "Translation of 'Balika Badhu: A Selected Anthology of Bengali Short Stories'" (2002). Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications. Paper 362. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub/362 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Translator'sl?rcfacc This project, which began with the desire to render into English a rather long tale by Bimal Kar about five years ago, eventually grew into a considerably more extended compilation of Bengali short stories by ten of the most well known practitioners of that art since the heyday of Rabindranath Tagore. The collection is limited in many ways, not the least of which being that no woman writer has been included, and that it contains only a baker's dozen stories (if we count Bonophool's micro-stories collectively as one )-a number pitifully small considering the vast and prolific field of authors and stories a translator has at his or her disposal. -

Subhash Chandra Bose and His Discourses: a Critical Reading”, Thesis Phd, Saurashtra University

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Thanky, Peena, 2005, “Subhash Chandra Bose and his discourses: A Critical Reading”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/827 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author SUBHASH CHANDRA BOSE AND HIS DISCOURSES: A CRITICAL READING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY, RAJKOT FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN ENGLISH Supervised by: Submitted by: Dr. Kamal Mehta Mrs. Peena Thanky Professor, Sainik School, Smt. H. S. Gardi Institute of Balachadi. English & Comparative (Dist. Jamnagar) Literary Studies, Saurashtra University, Rajkot. 2005 1 SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSE 1897 - 1945 2 SMT. H. S. GARDI INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH & COMPARATIVE LITERARY STUDIES SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY RAJKOT (GUJARAT) CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the work embodied in this thesis entitled "Subhash Chandra Bose and His Discourses : A Critical Reading" has been carried out by the candidate Mrs. Peena Thanky under my direct guidance and supervision for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts of Saurashtra University, Rajkot. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Chandra Shekahr Azad

Chandra Shekahr Azad drishtiias.com/printpdf/chandra-shekahr-azad Why in News On 23rd July, India paid tribute to the freedom fighter Chandra Shekahr Azad on his birth anniversary. Key Points Birth: Azad was born on 23rd July 1906 in the Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh. Early Life: Chandra Shekhar, then a 15-year-old student, joined a Non-Cooperation Movement in December 1921. As a result, he was arrested. On being presented before a magistrate, he gave his name as "Azad" (The Free), his father's name as "Swatantrata" (Independence) and his residence as "Jail". Therefore, he came to be known as Chandra Shekhar Azad. 1/2 Contribution to Freedom Movement: Hindustan Republican Association: After the suspension of the non- cooperation movement in 1922 by Gandhi, Azad joined Hindustan Republican Association (HRA). HRA was a revolutionary organization of India established in 1924 in East Bengal by Sachindra Nath Sanyal, Narendra Mohan Sen and Pratul Ganguly as an offshoot of Anushilan Samiti. Members: Bhagat Singh, Chandra Shekhar Azad, Sukhdev, Ram Prasad Bismil, Roshan Singh, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri. Kakori Conspiracy: Most of the fund collection for revolutionary activities was done through robberies of government property. In line with the same, Kakori Train Robbery near Kakori, Lucknow was done in 1925 by HRA. The plan was executed by Chandrashekhar Azad, Ram Prasad Bismil, Ashfaqulla Khan, Rajendra Lahiri, and Manmathnath Gupta. Hindustan Socialist Republican Association: HRA was later reorganised as the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA). It was established in 1928 at Feroz Shah Kotla in New Delhi by Chandrasekhar Azad, Ashfaqulla Khan, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee. -

History and Political Science

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 29.12.2017 and it has been decided to implement it from the educational year 2018-19. HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE STANDARD TEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune. The digital textbook can be obtained through DIKSHA App on a smartphone by using the Q. R. Code given on title page of the textbook and useful audio-visual teaching-learning material of the relevant lesson will be available through the Q. R. Code given in each lesson of this textbook. First Edition : 2018 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Reprint : Research, Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves October 2020 all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee Authors History Political Science Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre, Member Translation Scrutiny Dr Somnath Rode, Member Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Manjiri Bhalerao Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Dr Sanjot Apte Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Cover and Illustrations Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Shri. Devdatta Prakash Balkawade Typesetting Civics Subject Committee DTP Section, Balbharati Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Paper Prof. -

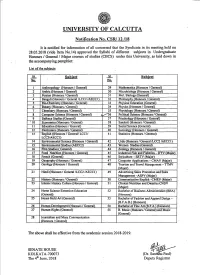

Final Draft BA (Honours)-CBCS Syllabus in Political Science, 2018 (Section I)

University of Calcutta Final Draft BA (Honours)-CBCS Syllabus in Political Science, 2018 (Section I) Core Courses [Fourteen courses; Each course: 6 credits (5 theoretical segment+ 1 for tutorial-related segment). Total: 84 credits (1400 marks). ♦ Each course carries 80 marks^ ^^ (plus 10 marks each for Attendance and Internal Assessment). ♦ Minimum 30 classes for Theory and 15 contact hours for Tutorial per module. ^End Semester Assessment for each course--- 65 marks for theoretical segment: 50 marks for subjective/descriptive questions + 15 marks for category of 1 mark-questions. Question Pattern for subjective/descriptive segment of 50 marks: 2 questions (within 100 words; one from each module) out of 4 (10 x2 = 20) + 2 questions (within 500 words; one from each module) out of 4 (15 x 2 = 30). ^^15 marks for tutorial-related segments as suggested below (any one item from each mode): i) Written mode: upto 1000 words for one Term Paper/upto 500 words for each of the two Term Papers/ equivalent Book Review/equivalent Comprehension/equivalent Quotation or Excerpt Elaboration. ii) Presentation Mode: Report Presentation/Poster Presentation/Field work--- based on syllabus-related and/or current topics (May be done in groups)[The modes and themes and/or topics are be decided by the concerned faculty members of respective colleges.] ♦ Core courses: First 2 each in Semesters 1 and 2;Next 3 each in Semesters 3 and 4; 2 each in Semesters 5 and 6. [Sequentially arranged] IMPORTANT NOTES: ♦ The Readings provided below include many of those of the UGC Model CBCS Syllabus in Political Science. For further details of Course Objectives and additional references it is advised that the UGC model CBCS syllabus* concerning relevant courses and topics be provided due importance and primarily consulted.