Subhash Chandra Bose and His Discourses: a Critical Reading”, Thesis Phd, Saurashtra University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

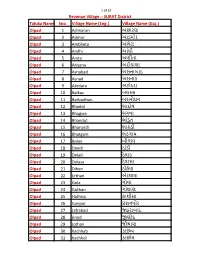

Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1

1 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1 Achharan અછારણ Olpad 2 Admor આડમોર Olpad 3 Ambheta અંભેટા Olpad 4 Andhi આંઘી Olpad 5 Anita અણીતા Olpad 6 Ariyana અરીયાણા Olpad 7 Asnabad અસનાબાદ Olpad 8 Asnad અસનાડ Olpad 9 Atodara અટોદરા Olpad 10 Balkas બલકસ Olpad 11 Barbodhan બરબોઘન Olpad 12 Bhadol ભાદોલ Olpad 13 Bhagwa ભગવા Olpad 14 Bhandut ભાંડુત Olpad 15 Bharundi ભારં ડી Olpad 16 Bhatgam ભટગામ Olpad 17 Bolav બોલાવ Olpad 18 Dandi દાંડી Olpad 19 Delad દેલાડ Olpad 20 Delasa દેલાસા Olpad 21 Dihen દીહેણ Olpad 22 Erthan એરથાણ Olpad 23 Gola ગોલા Olpad 24 Gothan ગોથાણ Olpad 25 Hathisa હાથીસા Olpad 26 Isanpor ઇશનપોર Olpad 27 Jafrabad જાફરાબાદ Olpad 28 Jinod જીણોદ Olpad 29 Jothan જોથાણ Olpad 30 Kachhab કાછબ Olpad 31 Kachhol કાછોલ 2 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 32 Kadrama કદરામા Olpad 33 Kamroli કમરોલી Olpad 34 Kanad કનાદ Olpad 35 Kanbhi કણભી Olpad 36 Kanthraj કંથરાજ Olpad 37 Kanyasi કન્યાસી Olpad 38 Kapasi કપાસી Olpad 39 Karamla કરમલા Olpad 40 Karanj કરંજ Olpad 41 Kareli કારલે ી Olpad 42 Kasad કસાદ Olpad 43 Kasla Bujrang કાસલા બજુ ઼ રંગ Olpad 44 Kathodara કઠોદરા Olpad 45 Khalipor ખલીપોર Olpad 46 Kim Kathodra કીમ કઠોદરા Olpad 47 Kimamli કીમામલી Olpad 48 Koba કોબા Olpad 49 Kosam કોસમ Olpad 50 Kslakhurd કાસલાખુદદ Olpad 51 Kudsad કુડસદ Olpad 52 Kumbhari કુભારી Olpad 53 Kundiyana કુદીયાણા Olpad 54 Kunkni કુંકણી Olpad 55 Kuvad કુવાદ Olpad 56 Lavachha લવાછા Olpad 57 Madhar માધ઼ ર Olpad 58 Mandkol મંડકોલ Olpad 59 Mandroi મંદરોઇ Olpad 60 Masma માસમા Olpad 61 Mindhi મીઢં ીં Olpad 62 Mirjapor મીરઝાપોર 3 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. -

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Subhash Chandra Bose

Subhash Chandra Bose drishtiias.com/printpdf/subhash-chandra-bose-3 Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose was a fierce nationalist, whose defiant patriotism made him one of the greatest freedom fighters in Indian history. He was also credited with setting up the Indian Army as a separate entity from the British Indian Army - which helped to propel the freedom struggle. Life Subhas Chandra Bose was born on 23rd January 1897, in Cuttack, Orissa Division, Bengal Province, to Prabhavati Dutt Bose and Janakinath Bose. After his early schooling, he joined Ravenshaw Collegiate School. From there he went to join Presidency College, Calcutta and was expelled due to his nationalist activities. Later, he went to University of Cambridge, U.K. In 1919, Bose headed to London to give the Indian Civil Services (ICS) examination and he was selected. Bose, however, resigned from Civil Services as he believed he could not side with the British. He was highly influenced by Vivekananda's teachings and considered him as his spiritual Guru. His political mentor was Chittaranjan Das. In 1921, Bose took over the editorship of the newspaper 'Forward', founded by Chittaranjan Das's Swaraj Party. In 1923, Bose was elected the President of the All India Youth Congress and also the Secretary of Bengal State Congress. He was also sent to prison in Mandalay in 1925 due to his connections with revolutionary movements where he contracted Tuberculosis. During the mid-1930s Bose travelled in Europe. He researched and wrote the first part of his book, The Indian Struggle, which covered the country’s independence movement in the years 1920–1934. -

School Vacancy Report

School Vacancy Report ગણણત/ સામાજક ાથિમકની ભાષાની િવાનન િવાનની ખાલી ખાલી પે સેટર શાળાનો ◌ી ખાલી ખાલી જલો તાલુકા ડાયસ કોડ શાળાનું નામ માયમ પે સેટર જયા જયા ડાયસ કોડ જયા જયા (ધોરણ ૧ (ધોરણ ૬ (ધોરણ (ધોરણ ૬ થી ૫) થી ૮) ૬ થી ૮) થી ૮) Surat Bardoli 24220108203 Balda Khadipar 24220108201 Balda Mukhya 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220100701 Rajwad 24220108201 Balda Mukhya 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220103002 Bardoli Kanya 24220103001 Bardoli Kumar 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220105401 Bhuvasan 24220105401 Bhuvasan 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102101 Haripura 24220101202 Kadod 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 2 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102301 Surali 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220102305 Surali Hat Faliya 24220102604 Madhi Vardha 0 0 1 0 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220106801 Vadoli 24220106401 Tarbhon 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Bardoli 24220103801 Mota 24220103601 Umarakh 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202401 Bhatlai 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202801 Junagan 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220202301 Vansva 24220202201 Damka 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220205904 Haidarganj 24220205901 Sachin 0 0 0 1 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220206302 Kanakpur GHB 24220205901 Sachin 0 1 0 0 ગુજરાતી Page No : 1 School Vacancy Report Surat Choryasi 24220206301 Kanakpur Hindi Med 24220205901 Scahin 0 1 2 0 હદ Surat Choryasi 24220208001 Paradi Kande 24220205901 Sachin 0 0 0 2 ગુજરાતી Surat Choryasi 24220206001 Talangpur 24220205901 -

Global Feminisms: Interview Transcripts: India Language: English

INDIA Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship Interview Transcripts: India Language: English Interview Transcripts: India Contents Acknowledgments 3 Shahjehan Aapa 4 Flavia Agnes 23 Neera Desai 48 Ima Thokchom Ramani Devi 67 Mahasweta Devi 83 Jarjum Ete 108 Lata Pratibha Madhukar 133 Mangai 158 Vina Mazumdar 184 D. Sharifa 204 2 Acknowledgments Global Feminisms: Comparative Case Studies of Women’s Activism and Scholarship was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan (UM) in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The project was co-directed by Abigail Stewart, Jayati Lal and Kristin McGuire. The China site was housed at the China Women’s University in Beijing, China and directed by Wang Jinling and Zhang Jian, in collaboration with UM faculty member Wang Zheng. The India site was housed at the Sound and Picture Archives for Research on Women (SPARROW) in Mumbai, India and directed by C.S. Lakshmi, in collaboration with UM faculty members Jayati Lal and Abigail Stewart. The Poland site was housed at Fundacja Kobiet eFKa (Women’s Foundation eFKa) in Krakow, Poland and directed by Slawka Walczewska, in collaboration with UM faculty member Magdalena Zaborowska. The U.S. site was housed at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan and directed by UM faculty member Elizabeth Cole. Graduate student interns on the project included Nicola Curtin, Kim Dorazio, Jana Haritatos, Helen Ho, Julianna Lee, Sumiao Li, Zakiya Luna, Leslie Marsh, Sridevi Nair, Justyna Pas, Rosa Peralta, Desdamona Rios and Ying Zhang. -

August 15, 1947 the Saddest Day in Pondicherry

August 15, 1947 The saddest day in Pondicherry Claude Arpi April 2012 Background: India becomes Independent On August 15, 1947 a momentous change occurred on the sub-continent: India became independent, though divided. Nehru, as the first Prime Minister uttered some words which have gone down in history: Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity. A few years ago, I studied the correspondence between the British Consul General in Pondicherry, Col. E.W Fletcher1 and the Indian Ministry of External Affairs and Commonwealth during these very special times. Fletcher who was the Indian Government’s informant in Pondicherry, still a French Colony, wrote to Delhi that the stroke of midnight did not change much in Pondicherry. Though technically the British Colonel was not supposed to have direct relations with the Government of India anymore, he continued to write to the Indian officials in Delhi. His correspondence was not even renumbered. His Secret Letter dated August 17, 1947 bears the reference D.O. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

'Netaji's Life Was More Important Than the Legends and Myths' Page 1 of 4

The Telegraph Page 1 of 4 Issue Date: Sunday , July 10 , 2011 ‘Netaji’s life was more important than the legends and myths’ Miami-based economist turned film-maker Suman Ghosh — who has also made a documentary on Amartya Sen — was in conversation with Sugata Bose, Netaji’s grandnephew, about the historian’s His Majesty’s Opponent — Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire on the morning of the launch of the Penguin book. Metro sat in on the Netaji adda. Excerpts… Suman Ghosh: You are a direct descendent of Subhas Chandra Bose and your father (Sisir Kumar Bose) was involved in the freedom struggle with him. Did you worry about objectivity in treating a subject that was so close to you? Sugata Bose: I made a conscious decision to write this book as a historian. Not as a Sugata Bose speaks with (right) family member. My father always used to tell me that Netaji believed that his country and Suman Ghosh at Netaji Bhavan. family were coterminous. So if I’m a member of the Bose family by an accident of birth so Picture by Bishwarup Dutta are all of the people of India. In some ways, if there is a problem of objectivity it would apply to most people and scholars of the subcontinent. But I felt I had acquired the necessary critical distance from my subject to embark on this project when I did. Ghosh: Netaji has always been shrouded in myths and mysteries. He has primarily been characterised as a revolutionary and a warrior. -

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru Views on Democratic Socialism

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 4; Issue 2; March 2018; Page No. 104-106 Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru views on democratic socialism Dr. Ashok Uttam Chothe HOD, Department of Political Science, New Arts, Commerce & Science College, Ahmednagaar, Maharashtra, India Abstract As a thinker he was passionately devoted to democracy and individual liberty this made it inconceivable for him to turn a comrade. He had confidence in man and love for enterprise Dynamism and dynamic were his most loved words. This loaned to his communism a dynamic character. He trusted that communism is more logical and valuable in the financial scene. It depends on logical strategies for endeavoring to comprehend the history, the past occasions and the laws of the improvement. He pursued it, since it can persuade us the reasons of neediness, worldwide clash and government. He understood that Laissez Faire was dead and the group must be composed to build up social and financial justice. Numerous variables contributed for the development of Democratic Socialism in the brain of Nehru. In England he was dubiously pulled in to the Fabians and Socialistic Ideas. When he took an interest in national development these thoughts again blended the coals of Socialistic Ideas in his mind this enthusiasm for communism principally got from books not from the immediate contacts with the wretchedness and misuse of poor by the rich. When he straightforwardly comes into contact with neediness of workers he felt that unimportant political opportunity was inadequate and without social flexibility individuals could gain no ground without social opportunity. -

SSM D[/JGFZGL ,. UIF TFZLB GFD TYF Smg8[S8 G\AZ ;CL VG[ ;DI 1

THE SOUTHERN GUJARAT COMMERCIAL TAX BAR ASSOCIATION l;SSM D[/JGFZG]\ l;SSM D[/JGFZGL ,. UIF TFZLB GFD TYF SMg8[S8 G\AZ ;CL VG[ ;DI ACHARYA KETAN NARENDRA B.COM., LL.B. Off. : U/G-35, CRYSTAL CHAMBER, MINI BAZAR, VARACHHA ROAD, SURAT Resi. : 402, VASUDEVPARK APPARTMENT, DHARAMNAGAR SOCIETY, A.K. ROAD, SURAT- Phone : (O)2566955 ® 2541566 Mobile : 9426845299 Birth Date : 29/07/1970 AGARWAL SUBHASH RATANLAL B.COM., Off. : A-2009-10,SHIV KRUPA TEXT. MARKET, KAMELA DARWAJA, RING ROAD, SURAT-395002 Resi. : PLOT NO.117,CHANDRALOK SOCIETY, PARVAT GAM, SURAT- Phone : (O)6622038/2355543 9879075048 Mobile : 9825642038 Birth Date : 04/12/1973 AGRAWAL NITISH RAGHUVIRBHAI B.COM.,A.C.A. Off. : G-1,TRIVIDH CHAMBERS, NR. RUSHABH PETROL PUMP, RING ROAD, SURAT-395002 Resi. : 67SURUCHI HOUSING SOCIETY, NR.UMRAV NAGAR, GHOD DOD ROAD, SURAT-395001 Phone : (O)2326581(R)3214932 Mobile : 987969009 Birth Date : 27/10/1984 AGRAWAL RAGHUVIR BHOLARAM M.COM.,LL.M. Off. : G-1,TRIVIDH CHAMBERS, NR.RUSHABH PETROL PUMP, RINGROAD, SURAT-395002 Resi. : 67,SURUCHI HOUSING SOCIETY, NEAR UMRAV NAGAR, GHOD DOD ROAD, SURAT-395001 Phone : (O)2326581(R)3214392 Mobile : 9427470067 Birth Date : 28/07/1950 1 THE SOUTHERN GUJARAT COMMERCIAL TAX BAR ASSOCIATION l;SSM D[/JGFZG]\ l;SSM D[/JGFZGL ,. UIF TFZLB GFD TYF SMg8[S8 G\AZ ;CL VG[ ;DI AGRAWAL RAJESH NATVERLAL B.Com., LL.B., ADVOCATE Off. : 6/834-835,102, ROYAL HOUSE, CHHAPARIA SHERI, MAHIDHARPURA, SURAT-395003 Resi. : G-203,BEJANWALA COMPLEX, OPP. SMC WEST ZONE OFFICE, TADWADI RANDER ROAD, SURAT-395009 Phone : (O)2411437(R)2769064 Mobile : 9825361405 Birth Date : 30/07/1952 AGRAWAL VEDRAJ RATANLAL B.COM.,F.C.A. -

Rhetorical Analysis on Expectations and Functions in Jawaharlal Nehru’S Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au Rhetorical Analysis on Expectations and Functions in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi Kangsheng Lai* Pingxiang University, China Corresponding Author: Kangsheng Lai, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history The paper introduces the life story of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and then analyzes Received: October 04, 2018 the relationship between the two great people in India. After Gandhi’s death, Jawaharlal Nehru Accepted: December 12, 2018 delivered the eulogy for commemorating his intimate comrade and respectful mentor Mahatma Published: February 28, 2019 Gandhi, the Father of India. Under generic constraints based on audience’s expectation and need, Volume: 10 Issue: 1 the eulogy is analyzed from the perspectives of two major expectations and five basic functions. Advance access: January 2019 Through the rhetorical analysis of Jawaharlal Nehru’s eulogy, it can be concluded that a good eulogy should meet audiences’ two major expectations and five basic functions. Conflicts of interest: None Funding: None Key words: Eulogy, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Expectation, Function INTRODUCTION Muslim-majority Pakistan. Religious violence took place in the Punjab and Bengal because of the substitution of Hindus, Life Story of Mahatma Gandhi Muslims, and Sikhs decided on setting up their own land. Mahatma Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869. He was Gandhi paid a visit to the places where religious violence an activist in India who struggled for the independence from broke out, intending to give the affected people solacement the British rule all his life. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code Amroli V.V Mandli Tal.Choryasi,Sura 0261- Gujarat Surat Amroli Br

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE AMROLI V.V MANDLI TAL.CHORYASI,SURA 0261- GUJARAT SURAT AMROLI BR. T-394107 AMROLI SDCB0000040 2499835 395244018 TAL.MAHUVA,SURAT- 02625- GUJARAT SURAT ANAVAL BR. 396510 ANAVAL SDCB0000020 252221 33,34 ASHRWAD TOWNSHIP,BAMROLI ROAD,UDHANA BAMROLI,SURAT- 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BAMROLI BR. 394210 SURAT SDCB0000063 2611222 395244029 SARDAR BARDOLI CITY CHOWK,TAL.BARDOL 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BR. I,SURAT-394160 BARDOLI SDCB0000002 220030 STATION BARDOLI ROAD,TAL.BARDOLI, 02622- GUJARAT SURAT STATION BR. SURAT-395003 BARDOLI SDCB0000012 225143 MAHUWA SUGAR FACORY TAL.MAHUVA,SURAT- 02625- GUJARAT SURAT BHAMANIYA BR. 394246 MAHUVA SDCB0000035 256849 NR.CHAITANIY APT.BHATAR ROAD,TAL.CHORYAS 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHATAR BR. I,SURAT-395001 SURAT SDCB0000039 2241108 395244012 TAL.MANDVI,SURAT- 02623- GUJARAT SURAT BHAUDHAN BR. 394140 BAUDHAN SDCB0000051 251251 CHALTHAN SUGAR FACTORY COMPOUND,TAL.PAL 02622- GUJARAT SURAT CHALTHAN BR. SANA,SURAT-394305 CHALTHAN SDCB0000016 281080 395244020 KANJIBHAI DESAI CHOWK BAZAR BHAVAN,TAL.CHORY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BR. ASI,SURAT-395003 SURAT SDCB0000024 2599070 395244005 CONTROL CENTRE CONTROL RTGS DEPT., MAIN CENTRE RTGS BRANCH, KANPITH, 0261- 0261- GUJARAT SURAT DEPT. CHUTAPOOL, SURAT SURAT SDCB0000001 2597730 0261-2594739 2597738 DOLVAN CHAR TAL.VYARA,SURAT- 02626- GUJARAT SURAT RASTA BR. 394635 DOLVAN SDCB0000028 251221 GANGADHARA TAL.PALSANA,SURAT- GANGADHR 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BR. 394310 A SDCB0000032 263224 MAZDA GHODOD ROAD APT.TAL.CHORYASI, 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BR. SURAT-395001 SURAT SDCB0000041 2653477 395244014 GHEE KANTA ROAD,TAL.CHORAYS 0261- GUJARAT SURAT HARIPURA BR. I,SURAT-395003 SURAT SDCB0000038 2423472 395244011 MAHAVIR CHOWK,TAL.CHORY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT J.P ROAD BR.