"Rewriting the Ramayana: Chandrabati and Molla" by Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

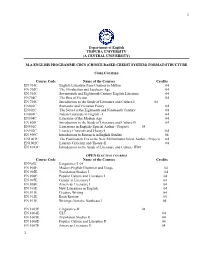

Ma English Programme Cbcs (Choice Based Credit System)

1 Department of English TRIPURA UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) M.A ENGLISH PROGRAMME CBCS (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FORMAT/STRUCTURE CORE COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits EN 701C English Literature from Chaucer to Milton 04 EN 702C The Elizabethan and Jacobean Age 04 EN 703C Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century English Literature 04 EN704C The Rise of Fiction 04 EN 705C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture-I 04 EN801C Romantic and Victorian Poetry 04 EN802C The Novel in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century 04 EN803C Indian Literature in English - I 04 EN804C Literature of the Modern Age 04 EN 805C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture-II 04 EN901C Literatures in English (Special Author - Project) 04 EN902C Literacy Criticism and Theory-I 04 EN 909C Introduction to Research in English Studies 04 EN1001C The Postmodern Era to the New Millennium (Select Author - Project) 04 EN1002C Literary Criticism and Theory-II 04 EN 1013C Introduction to the Study of Literature and Culture- III04 OPEN ELECTIVE COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits EN903E Linguistics-I 04 EN 904E Modern English Grammar and Usage 04 EN 905E Translation Studies I 04 EN 906E Popular Culture and Literature I 04 EN 907E Gender in Literature I 04 EN 908E American Literature I 04 EN 910E New Literatures in English 04 EN 911E Creative Writing 04 EN 912E Book Review 04 EN 913E Writings from the Northeast I 04 EN 1003E Linguistics-II 04 EN 1004E ELT 04 EN 1005E Translation Studies II 04 EN 1006E Popular Culture and Literature II 04 EN 1007E American Literature II 04 1 2 EN 1008E Literature and Industry 04 EN 1009E Folk and Oral Literatures 04 EN 1010E Writings from the Northeast II 04 EN 1011E New Literatures in English II 04 EN 1012E Gender in Literature II 04 COMPULSORY FOUNDATION COURSES Course Code Name of the Courses Credits Basics of Computer Applications Skill I 04 Seminar Presentation (No End-semester examination. -

TIWARI-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Bhavya Tiwari 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Bhavya Tiwari Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South Committee: Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Supervisor David Damrosch Martha Ann Selby Cesar Salgado Hannah Wojciehowski Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South by Bhavya Tiwari, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication ~ For my mother ~ Acknowledgements Nothing is ever accomplished alone. This project would not have been possible without the organic support of my committee. I am specifically thankful to my supervisor, Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, for giving me the freedom to explore ideas at my own pace, and for reminding me to pause when my thoughts would become restless. A pause is as important as movement in the journey of a thought. I am thankful to Martha Ann Selby for suggesting me to subhead sections in the dissertation. What a world of difference subheadings make! I am grateful for all the conversations I had with Cesar Salgado in our classes on Transcolonial Joyce, Literary Theory, and beyond. I am also very thankful to Michael Johnson and Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski for patiently listening to me in Boston and Austin over luncheons and dinners respectively. I am forever indebted to David Damrosch for continuing to read all my drafts since February 2007. I am very glad that our paths crossed in Kali’s Kolkata. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210

ISSN-L 0537-1988 UGC Approved Journal (Journal Number 46467, Sl. No. 228) (Valid till May 2018. All papers published in it were accepted before that date) Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210 56 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Vol. LVI 2019 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The responsibility for facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any in this journal, is entirely that of the author(s). The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 56 2019 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES) published since 1940 accepts scholarly papers presented by the AESI members at the annual conferences of Association for English Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the copies of journal for home, college, university/departmental library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri by sending an e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are requested to place orders on behalf of their institutions for one or more copies. Orders by post can be sent to the Editor- in-Chief, Indian Journal of English Studies, Anand Math, Near St. Paul School, Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 (Bihar) India. ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA Price: ``` 350 (for individuals) ``` 600 (for institutions) £ 10 (for overseas) Submission Guidelines Papers presented at AESI (Association for English Studies of India) annual conference are given due consideration, the journal also welcomes outstanding articles/research papers from faculty members, scholars and writers. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Annual Report

INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES KOLKATA Annual Report 2010-11 Institute of Development Studies Kolkata 27/D, DD Block, Sector I Salt Lake, Kolkata 700064 Tel:-+ 91(033)2321 3120/3121 Fax: +91(033)2321 3119 Website: www.idsk.edu.in CONTENTS I Introduction 1 II Research Programmes 3 III Collaborations 9 IV Teaching and Research Guidance 10 V Seminars, Workshops & Round Table 12 VI Library 15 VII Academic Activities of Faculty Members 16 VIII Academic Activities of Rabindranath Tagore 24 Centre for Human Development Studies IX Publications 27 X Members of Faculty / Visiting Faculty 33 XI Governing Council 35 1 I Introduction The Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK) has been promoted by the Government of West Bengal as an autonomous centre of excellence in social sciences. It was founded in 2002 as a society with an autonomous governing body, with one of the most eminent historians in India, with one of the most eminent historians in India, Professor Irfan Habib as President, Professor Amiya Kumar Bagchi as Director and with a Governing Council on which are represented the current or former Vice-Chancellors of two leading Universities in West Bengal, namely Calcutta University and Jadavpur University. The new Governing Council constituted in 2010 includes such eminent academics as Professor Prabuddha Nath Roy as President, Professor Amiya Kumar Bagchi as Director, Professor Asis Kumar Banerjee as Secretary and Professor Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, Professor Atis Dasgupta, Professor Subimal Sen, Professor Ratan Khasnabis, Professor Abhijit Chowdhury and Professor Sarmila Banerjee as its members. The IDSK is devoted to advanced academic research and informed policy advice in the areas of literacy, education, health, gender issues, employment, technology, communication, human sciences and economic development. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh a large number of languages in India, and we have lots BHASHA SAMMAN of literature in those languages. Akademi is taking April 25, 2017, Vijayawada more responsibility to publish valuable literature in all languages. After that he presented Bhasha Samman to Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao, Prof. T.R Damodaran and Smt. T.S Saroja Sundararajan. Later the Awardees responded. Sri Nagalla Guruprasadarao expressed his gratitude towards the Akademi for the presentation of the Bhasha Samman. He said that among the old poets Mahakavai Tikkana is his favourite. In his writings one can see the panoramic picture of Telugu Language both in usage and expression. He expressed his thanks to Sivalenka Sambhu Prasad and Narla Venkateswararao for their encouragement. Prof. Damodaran briefed the gathering about the Sourashtra dialect, how it migrated from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu and how the Recipients of Bhasha Samman with the President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi cultural of the dialect has survived thousands of years. He expressed his gratitude to Sahitya Akademi for Sahitya Akademi organised the presentation of Bhasha honouring his mother tongue, Sourashtra. He said Samman on April 25, 2017 at Siddhartha College of that the Ramayana, Jayadeva Ashtapathi, Bhagavath Arts and Science, Siddhartha Nagar, Vijayawada, Geetha and several books were translated into Andhra Pradesh. Sahitya Akademi felt that in a Sourashtra. Smt. T.S. Saroja Sundararajan expressed multilingual country like India, it was necessary to her happiness at being felicitated as Sourashtrian. She extend its activities beyond the recognized languages talked about the evaluation of Sourashtra language by promoting literary activities like creativity and and literature. -

Nabaneeta Dev Sen Hardback with Dust Jacket

ISBN: 978-93-86906-86-1 TRANSLATION/FICTION IMPRINT: THORNBIRD `395 HB NIYOGI BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED Block D, Building No. 77, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-1, New Delhi-110020, INDIA Phone: 011 26816301, 26818960, Email: [email protected], Website: www.niyogibooksindia.com TRANSLATION/FICTION `395 ISBN: 978-93-86906-86-1 216mm x 140mm; 196pp Book Print Paper by Black and white Nabaneeta Dev Sen Hardback with dust jacket mi Anupam (I, Anupam) was first published in Bengali in the Sharadiya Ananda Bazaar in 1976. It was the first novel on the Naxal Movement in West Bengal. It came out as a book in 1978. ASome prominent intellectuals of West Bengal had played a strange two-faced role in this political movement. They encouraged and led the youth, who put their lives at stake and fought for the cause. However, most of these intellectual leaders failed to take responsibility later on when they were needed the most. Ami Anupam is about one such betrayal. The novel is a sharp depiction of those turbulent times. Nabaneeta Dev Sen is one of the prominent Bengali litterateurs of our times with more than 80 books to her name. A student of Presidency, Jadavpur, Indiana, Harvard, Cambridge, and Berkeley universities, and an outstanding academic, she recently retired as Professor of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. Her works reflect her intellection on an amazing array of social, political, and psychological topics, under different genres like poetry, novels, short stories, plays, literary criticism, travelogues, translations, and children’s literature. Her Radhakrishnan Memorial Lecture series at Oxford University, a pioneering work on women’s Ramayanas, has started a new school of studies on Sita across the world. -

Literature Festivals and Talk-Culture In

POSSIBLE INSTITUTIONS: LITERATURE FESTIVALS AND TALK-CULTURE IN INDIA By SUSHIL SIVARAM A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program of Literatures in English Written under the direction of Mukti Lakhi Mangharam & Stéphane Robolin And approved by ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Possible Institutions: Literature Festivals and Talk-Culture in India by SUSHIL SIVARAM Dissertation Directors: Mukti Lakhi Mangharam & Stéphane Robolin This dissertation sets out to understand the proliferation of literature festivals in India since the mid-2000s. These festivals serve cultural, economic and political functions in a dynamic field characterized by varying degrees of competition and co-operation between different literary cultures in multiple languages, the uneven legitimation and reception of culture by different class formations, and the multiple locations where the humanities are practiced. Against this complex setting, I demonstrate that the literature festivals attempt to find unique ways to connect and in turn reimagine a fragmented and plural literary field in the public sphere. This work specifically turns to the producers, managers and the writer- curators of three festivals to understand what drives -

Nabard-Digest.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS GOVERNMENT SCHEMES Schemes Launched By Ministry Of Drinking Water & Sanitation .................................................... 7 Atal Bhoojal Yojana - Highlights ........................................................................................................... 8 Important Schemes In Union Budget (2018-19) ............................................................................... 10 KUSUM- Kisan Urja Suraksha Evam Utthan Maha Abhiyan ........................................................... 13 Prime Minister's Employment Generation Programme ................................................................... 15 RISE Scheme .......................................................................................................................................... 16 Parivartan Scheme ................................................................................................................................ 17 Asmita Yojana ........................................................................................................................................ 18 National Deworming Initiative ............................................................................................................ 19 Khelo India School Games Launched By Modi ................................................................................. 20 Zero Budget Natural Farming ............................................................................................................. 21 Promote Young Scientists And Researchers -

Banking and Finance

E V E R Y I N F O R M A T I O N Y O U N E E D R E L A T E D T O Y O U R E X A M S CURRENT AFFAIRS 1 0 0 P R A C T I C E Q U E S T I O N S I N C L U D E D Career & Courses NOVEMBER 2019 CAREER & COURSES 1 Current Affairs Magazine Contents IMPORTANT DAYS.............................................................................................................. 2 APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATION................................................................................13 AWARDS AND HONOUR...................................................................................................35 BANKING AND FINANCE..................................................................................................53 BOOKS AND AUTHORS....................................................................................................75 BUSINESS AND ECONOMY...............................................................................................79 DEFENCE......................................................................................................................... 86 INTERNATIONAL............................................................................................................104 MOU.............................................................................................................................. 110 NATIONAL..................................................................................................................... 119 OBITUARY....................................................................................................................