Faith-Based Organizations in Development Discourses And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plight of German Missions in Mandate Cameroon: an Historical Analysis

Brazilian Journal of African Studies e-ISSN 2448-3923 | ISSN 2448-3907 | v.2, n.3 | p.111-130 | Jan./Jun. 2017 THE PLIGHT OF GERMAN MISSIONS IN MANDATE CAMEROON: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Lang Michael Kpughe1 Introductory Background The German annexation of Cameroon in 1884 marked the beginning of the exploitation and Germanization of the territory. While the exploitative German colonial agenda was motivated by economic exigencies at home, the policy of Germanization emerged within the context of national self- image that was running its course in nineteenth-century Europe. Germany, like other colonial powers, manifested a faulty feeling of what Etim (2014: 197) describes as a “moral and racial superiority” over Africans. Bringing Africans to the same level of civilization with Europeans, according to European colonial philosophy, required that colonialism be given a civilizing perspective. This civilizing agenda, it should be noted, turned out to be a common goal for both missionaries and colonial governments. Indeed the civilization of Africans was central to governments and mission agencies. It was in this context of baseless cultural arrogance that the missionization of Africa unfolded, with funds and security offered by colonial governments. Clearly, missionaries approved and promoted the pseudo-scientific colonial goal of Europeanizing Africa through the imposition of European culture, religion and philosophy. According to Pawlikova-Vilhanova (2007: 258), Christianity provided access to a Western civilization and culture pattern which was bound to subjugate African society. There was complicity between colonial governments and missions in the cultural imperialism that coursed in Africa (Woodberry 2008; Strayer 1976). By 1884 when Germany annexed Cameroon and other territories, the exploitation and civilization of African societies had become a hallmark 1 Department of History, University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon. -

THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT in the AUGUSTANA CHURCH the American Church Is Made up of Many Varied Groups, Depending on Origin, Divisions, Changing Relationships

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Augustana Historical Society Publications Augustana Historical Society 1984 The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks Part of the History Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation "The iM ssionary Spirit in the Augustana Church" (1984). Augustana Historical Society Publications. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/ahsbooks/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Augustana Historical Society at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Augustana Historical Society Publications by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Missionary Sphit in the Augustana Church George F. Hall \ THE MISSIONARY SPIRIT IN THE AUGUSTANA CHURCH The American church is made up of many varied groups, depending on origin, divisions, changing relationships. One of these was the Augustana Lutheran Church, founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants and maintain ing an independent existence from 1860 to 1962 when it became a part of a larger Lutheran community, the Lutheran Church of America. The character of the Augustana Church can be studied from different viewpoints. In this volume Dr. George Hall describes it as a missionary church. It was born out of a missionary concern in Sweden for the thousands who had emigrated. As soon as it was formed it began to widen its field. Then its representatives were found in In dia, Puerto Rico, in China. The horizons grew to include Africa and Southwest Asia. Two World Wars created havoc, but also national and international agencies. -

Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission In

Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 1 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission in Northern Karnataka 1837-1852 Section Five: 1845-1849 General Survey, mission among the "Canarese and in Tulu-Land" 1846 pp. 5.2-4 BM Annual Report [1845-] 1846 pp.5.4-17 Frontispiece & key: Betgeri mission station in its landscape pp.5.16-17 BM Annual Report [1846-] 1847 pp. 5.18-34 Frontispiece & key: Malasamudra mission station in its landscape p.25 Appx. C Gottlob Wirth in the Highlands of Karnataka pp. 5.26-34 BM Annual Report [1847-] 1848 pp. 5.34-44 BM Annual Report [1848-] 1849 pp. 5.45-51 Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 2 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Mission among the Canarese and in Tulu-Land1 [This was one of the long essays that the Magazin für die neueste Geschichte published in the 1840s about the progress of all the protestant missions working in different parts of India (part of the Magazin's campaign to inform its readers about mission everywhere.2 In 1846 the third quarterly number was devoted to the area that is now Karnataka. The following summarises some of the information relevant to Northern Karnataka and the Basel Mission (sometimes referred to as the German Mission). Quotations are marked with inverted commas.] [The author of the essay is not named, and the report does not usually specify from which missionary society the named missionaries came. -

Basel German Evangelical Mission

THE SIXTY-FIRST REPORT OF TH E BASEL GERMAN EVANGELICAL MISSION IN SOUTH-WESTERN INDIA FOR THE YEAR 1900 MANGALORE PRINTED AT THE BASEL MISSION PRESS 1901 European missionaries o f tixe B a s e l G-erias-aaa. ZO-^ra-ia-g-elical S cission .. Corrected up to the ist May 1 901. [The letter (m) after the names signifies “married”, and the letter (w) “widower”. The names of unordained missionaries are marked with an asterisk.] N ative D ate of Name A ctiv e Station. Country Service 1. W. Stokes (m) India 1860 Kaity (Coonoor) 2. S. Walter (m) Switzerland 1865 Vaniyankulamlj B. G. Ritter (m) Germany 1869 Mulki (S. Cañara) 4. J. A. Brasehe (m) do. 1869 Udipi do. 5. W. Sikemeier (m) Holland 1870 Mercara (Coorg) 6. J. Hermelink (m) Germany 1872 Mangalore 7. G. Grossmann (m) Switzerland 1874 Kotagiri (Nilgiri) 8. J. Baumann (m)* do. 1874 Mangalore 9. W. Lütze (m) Germany 1875 Kaity (Niigiri) 10. J. B. Veil (m)* do. 1875 Mercara (Coorg) : 11. L. J. Frohnmeyer (m) do. 1876 Tellicherry (Nettur) 12. J. G. Kiihnle (m) do. 1878 Palghat 13. H. Altenmüller (m)* do. 1878 Mangalore 14. C. D. Warth (m) do. 1878 Bettigeri 15. Chr. Keppler (m) do. 1879 Udipi 16. J. J. Jaus (m) do. 1879 Calicut 17. F. Stierlin (m)* do. 1880 Mangalore 18. K. Ernst (m) do. 1881 Dharwar 19. F. Eisfelder (m) do. 1882 Summadi-Guledgudd 20. M. Schaible (m) do. 1883 Mangalore 21. B. Liithi (m) Switzerland 1884 do. 22. K. Hole (m) Germany 1884 Cannanore 23. -

The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner

“Obstinate” Pastor and Pioneer Historian: The Impact of Basel Mission Ideology on the Thought of Carl Christian Reindorf Heinz Hauser-Renner n 1895, after twenty-five years of historical and ethnological Reindorf’s Western Education Iresearch, Carl Christian Reindorf, a Ghanaian pastor of the Basel Mission, produced a massive and systematic work about Reindorf’s Western education consisted of five years’ attendance the people of modern southern Ghana, The History of the Gold at the Danish castle school at Fort Christiansborg (1842–47), close Coast and Asante (1895).1 Reindorf, “the first African to publish to Osu in the greater Accra area, and another six years’ training at a full-length Western-style history of a region of Africa,”2 was the newly founded Basel Mission school at Osu (1847–55), minus a born in 1834 at Prampram/Gbugblã, Ghana, and he died in 1917 two-year break working as a trader for one of his uncles (1850–52). at Osu, Ghana.3 He was in the service of the Basel Mission as a At the Danish castle school Reindorf was taught the catechism and catechist and teacher, and later as a pastor until his retirement in arithmetic in Danish. Basel missionary Elias Schrenk later noted 1893; but he was also known as an herbalist, farmer, and medi- that the boys did not understand much Danish and therefore did cal officer as well as an intellectual and a pioneer historian. The not learn much, and he also observed that Christian principles intellectual history of the Gold Coast, like that of much of Africa, were not strictly followed, as the children were even allowed to is yet to be thoroughly studied. -

Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity'

H-Africa Mohr on Grant, 'Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity' Review published on Thursday, January 28, 2021 Paul Glen Grant. Healing and Power in Ghana: Early Indigenous Expressions of Christianity. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2020. 341 pp. $59.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-4813-1267-7. Reviewed by Adam H. Mohr (University of Pennsylvania) Published on H-Africa (January, 2021) Commissioned by David D. Hurlbut (Independent Scholar) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=55363 Scholars of global Christianity like Philip Jenkins inThe Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (2011) argue that a distinguishing feature of African Christianity comparative to other regional Christianities is its focus on healing. It is also an idea I have been trying to develop in my own writing about African Christianity, particularly my first book,Enchanted Calvinism: Labor Migration, Afflicting Spirits, and Christian Therapy in the Presbyterian Church of Ghana (2013) as well as my research and writing on Faith Tabernacle in West Africa. Here, for the first time, Paul Grant has examined the precolonial mission from Basel in Ghana to detail this argument in the earliest days of mission in West Africa. A strong link is made to the recent research on Pentecostalism in Ghana, where Grant argues that there are ontological and epistemological continuities between the type of Christianity established in the Akuapem hills in the nineteenth century and late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Pentecostalism, even without institutional continuity. The point here echoes Jenkins’s observation about popular Christianity in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: Ghanaian Christianity from its earliest times was primarily about healing, protection, and power in its broad, expansive, African qualities. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 271 366 SO 017 295 AUTHOR Salamone, Frank A., Ed. TITLE Anthropologists and Missionaries. Part II. Studies in Third World Societies. Publication Number Twenty-Six. INSTITUTION College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Dept. of Anthropology. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 314p.; For part Iof this study, see SO 017 268. For other studies in this series, see ED 251 334 and SO 017 296-297. AVAILABLE FROM Studies in Third World Societies, Department of Anthropology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA 23185 ($20.00; $35.00 set). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Anthropology; *Clergy; Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Influences; Cultural Pluralism; Culture Conflict; Developed Nations; *Developing Nations; Ethnography; Ethnology; *Global Aoproach; Modernization; Non Western Civili%ation; Poverty; Religious Differences; Religious (:ganizations; *Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences; Traditionalism; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Missionaries ABSTRACT The topics of anthropologist-missionary relationships, theology and missiology, research methods and missionary contributions to ethnology, missionary training and methods, and specific case studies are presented. The ten essays are: (1) "An Ethnoethnography of Missionaries in Kalingaland" (Robert Lawless); (2) "Missionization and Social Change in Africa: The Case of the Church of the Brethren Mission/Ekklesiyar Yan'Uwa Nigeria in Northeastern Nigeria" (Philip Kulp); (3) "The Summer Institute -

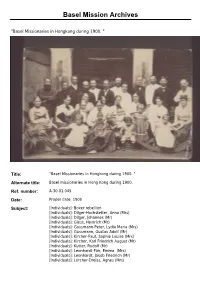

"Basel Missionaries in Hongkong During 1900. "

Basel Mission Archives "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Title: "Basel Missionaries in Hongkong during 1900. " Alternate title: Basel missionaries in Hong Kong during 1900. Ref. number: A-30.01.045 Date: Proper date: 1900 Subject: [Individuals]: Boxer rebellion [Individuals]: Dilger-Hochstetter, Anna (Mrs) [Individuals]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Individuals]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Gussmann-Peter, Lydia Maria (Mrs) [Individuals]: Gussmann, Gustav Adolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Kircher-Faut, Sophie Louise (Mrs) [Individuals]: Kircher, Karl Friedrich August (Mr) [Individuals]: Kutter, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Leonhardt-Fäh, Emma (Mrs) [Individuals]: Leonhardt, Jakob Friedrich (Mr) [Individuals]: Lörcher-Dreiss, Agnes (Mrs) Basel Mission Archives [Individuals]: Lörcher, Jakob Gottlob (Mr) [Individuals]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Individuals]: Ott-Walther, Wilhelmine Juliane (Mrs) [Individuals]: Ott, Rudolf (Mr) [Individuals]: Reusch-Keller, Pauline (Mrs) [Individuals]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Individuals]: Rohde, Hermann (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze, Maria Rudolfine Agnes (child) [Individuals]: Schultze, Otto Karl Eduard (Mr) [Individuals]: Ziegler, Johann Georg (Mr) [Individuals]: Schultze-Michel, Sophie (Mrs) [Individuals]: Rohde-Kopp, Rosina Christ. (Mrs) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Dilger, Johannes (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Giess, Heinrich (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Lutz, Samuel (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Reusch, Christian Gottlieb (Mr) [Photographers / Photo Studios]: Schultze, -

Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood Studies in Christian Mission

Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood Studies in Christian Mission General Editors Marc R. Spindler, Leiden University Heleen L. Murre-van den Berg, Leiden University Editorial Board Peggy Brock, Edith Cowan University James Grayson, University of Sheffield David Maxwell, Keele University VOLUME 39 Encounters in Quest of Christian Womanhood The Basel Mission in Pre- and Early Colonial Ghana By Ulrike Sill LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Cover illustration: Archive Mission 21/Basel Mission QD-30.016.0009 “Indigenous teachers. In the centre of the front row: Mrs Lieb.” Ghana Taken Between 1.01.1881 and 31.12.1900 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sill, Ulrike. Encounters in quest of Christian womanhood : the Basel Mission in pre- and early colonial Ghana / by Ulrike Sill. p. cm. — (Studies in Christian mission, 0924-9389 ; v. 39) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-18450-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Missions—Ghana—History—19th century. 2. Christian women—Ghana— History—19th century. 3. Evangelische Missionsgesellschaft in Basel—History—19th century. 4. Ghana—Church history—19th century. I. Title. II. Series. BV3625.G6S56 2010 266’.0234940667082—dc22 2010011777 ISSN 0924-9389 ISBN 978 90 04 18888 4 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence from Africa and Implications for Development

The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence from Africa and Implications for Development Remi Jedwab and Felix Meier zu Selhausen and Alexander Moradi∗ May 31, 2019 Abstract How did Christianity expand in sub-Saharan Africa to become the continent’s dominant religion? Using annual panel data on all Christian missions from 1751 to 1932 in Ghana, as well as cross-sectional data on missions for 43 sub-Saharan African countries in 1900 and 1924, we shed light on the spatial dynamics and determinants of this religious diffusion process. Missions expanded into healthier, safer, more accessible, and more developed areas, privileging these locations first. Results are confirmed for selected factors using various identification strategies. This pattern has implications for extensive literature using missions established during colonial times as a source of variation to study the long-term economic effects of religion, human capital and culture. Our results provide a less favorable account of the impact of Christian missions on modern African economic develop- ment. We also highlight the risks of omission and endogenous measurement error biases when using historical data and events for identification. JEL Codes: N3, N37, N95, Z12, O12, O15 Keywords: Economics of Religion; Religious Diffusion; Path Dependence; Eco- nomic Development; Compression of History; Measurement; Christianity; Africa ∗Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Department of Economics, George Washington University, and Development Research Group, The World Bank, [email protected]. Felix -

Bibliography on “Women and Mission”

BIBLIOGRAPHY ON “ WOMEN AND M ISSION”1 ACCORDING TO A. ALPHABETICAL ORDER B. REGION, DENOMINATION OR M ISC. C. CHRONOLOGY A. B IBLIOGRAPHY A CCORDING TO A LPHABETICAL O RDER I. MONOGRAPHIES AND ANTHOLOGIES 1. …die ist wie eine Kokospalme gepflanzt an den Wasserbächen, Verlag der Ev.-Luth. Mission, Erlangen 1992, 47p.. 2. A Few words to Bible mission-women. [Microform], London, Wertheim, MacIntosh & Hunt, 1861, 16 p.. 3. ALCOTT, William A.: Letters to a sister or Woman's mission, to accompany the Letters to young men, Geo. H. Derby, Buffalo 1850. 4. AMERICAN BAPTIST FOREIGN MISSION SOCIETY: Baptists in world service, Woman's American Baptist Foreign Mission Society, Boston 1918, 136 p.. 5. ARBEITSGEMEINSCHAFT DEUTSCHER FRAUENMISSIONEN: Brennende Fragen der Frauenmission 1.Heft, Brennende Fragen der Frauenmission o1, Verlag der Bücherstube der Mädchen-Bibel-Kreise, Leipzig 1928, 22p.. 6. ARBEITSGEMEINSCHAFT DEUTSCHER FRAUENMISSIONEN: Das Erwachen der Frau in aller Welt, Brennende Fragen der Frauenmission o2, Verlag der Bücherstube der Mädchen-Bibel-Kreise, Leipzig 1929, 22p.. 7. ARBEITSGEMEINSCHAFT DEUTSCHER FRAUENMISSIONEN: Der Anteil der Frau an der ärztlichen Mission, Brennende Fragen der Frauenmission o3, Verlag der Bücherstube der Mädchen- Bibel-Kreise, Leipzig 1930, 22p.. 8. ARBEITSGEMEINSCHAFT DEUTSCHER FRAUENMISSIONEN: Eignung zum Dienst, Brennende Fragen der Frauenmission o4, Verlag der Bücherstube der Mädchen-Bibel-Kreise, Leipzig 1930, 21p.. 9. ATHYAL, Sakhi Mariamma: Indian women in mission, Mission educational books series no. 7, Mission Educational Books, Madhupur/ Bihar 1995, 118 p.. 1 Compiled by Friederike Humboldt, WCC Study-Process on Women in Mission, Geneva 2002. By courtesy of Aruna Gnanadason. 1 10. BAHR, Diana Meyers: From mission to metropolis. -

A Study of the Basel Mission Trading Company from 1859 to 1917

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA ECONOMIC ENTERPRISES OF THE BASEL MISSION SOCIETY IN THE GOLD COAST: A STUDY OF THE BASEL MISSION TRADING COMPANY FROM 1859 TO 1917 JULIET OPPONG-BOATENG (10396805) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE M.PHIL DEGREE IN AFRICAN STUDIES JULY, 2014 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I declare that I have personally undertaken this study under supervision and it is my independent and original work. This thesis has not been submitted in any form to any other institution for the award of another degree. Where other sources of information have been cited, they have been duly acknowledged. Student JULIET OPPONG-BOATENG (10396805) ……………………………………… …………………………………… Signature Date Supervisors PROF. IRENE K. ODOTEI ……………………………………… …………………………………… Signature Date DR. EBENEZER AYESU ……………………………………… …………………………………… Signature Date i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT During the ninety years of operation on the Gold Coast (1828-1918), the Basel missionaries did not limit themselves to their primary task of evangelism. As part of the efforts to achieve their aim of total social transformation of converts, the missionaries promoted the establishment of schools, linguistic studies, agricultural experimentation and other economic ventures. A trading post which evolved into the Basel Mission Trading Company (BMTC) was established at Christiansborg in 1859 to take charge of all their economic ventures. This study documents the attempt by the Basel Mission Trading Company to transmit the Mission’s work ethic and practices to its converts through its operations.